Ibn Rushd - Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd (Averroes)

Ibn Rushd

I

Ibn Rushd (1126 AD - 1198 AD) is one of the most famous philosophers in the tradition of Islam, who attempted to build a great bridge between the East and the West during the 12th century. He was born in Spain at Cordova, where his father and grandfather had been Cadis. He had, therefore, a good background of jurisprudence and he himself was appointed as Cadi, first in Seville, and subsequently in Cordova. But his interests extended to theology, medicine, mathematics, astronomy and philosophy. 'Caliph' Abu Yaqub Yusuf took him into favour, considering the young man's capacity to make an analysis of the works of Aristotle. He was also made his physician in 1184 AD. Two years later, when the ruler, unfortunately, passed away, his successor,

Yaqub Al-Mansur, continued his father's patronage. This patronage lasted eleven years, but as he began to be alarmed by the opposition of the orthodox theologians to this great philosopher, he deprived him of his position and exiled him, first to a small place near Cordova, and then to Morocco. Ibn Rushd was accused of cultivating the philosophy of the ancients at the expense of the true faith. Al-Mansur published an edict to the effect that God had decreed hell-fire for those who thought that truth could be found by the unaided reason. Anyone who has studied Ibn Rushd will find that his philosophy was deeply respectful to faith, and even though he was inclined to stretch the capacity of reason to its farthest limits, he maintained that there are truths which can be known only through revelation. Thus, his exile was based on a misunderstanding of the philosophy that he had developed. Fortunately, Ibn Rushd was taken back into favour shortly before his death. Ibn Rushd or Averroes as he was called in Europe was a colossal scholar, considering that

he made three kinds of commentaries in Latin or Hebrew for Aristotle's 'Second Analytic', 'Physics', 'Sky', 'The Soul', and the 'Metaphysics', although he did not make any long commentary for the other works of Aristotle, and none at all for 'History of Animals', and 'Politics'. On the other hand, he made in Arabic medium commentaries on 'Politics', 'Rhetoric', and translation of fragments of Alexander's commentary on Metaphysics. In addition to these commentaries, Ibn Rushd wrote an original work, 'Tahafut al-Tahafut' (Vanity of Vanities or Destruction of the Destructions) in answer to Alagazel's book called 'Destruction of Philosophers'. He also wrote a commentary on Plato's 'Republic' as also opinions on Al-Farabi's 'Logic' . He was also the author of works on jurisprudence, astronomy and medicine.

Ibn Rushd was an acute philosopher, and he had also a catholic and synthetic mind. This great mind was ardently obedient to the revelation contained in the Holy Koran, as is evident from his abiding dedication to the task

of assigning the highest place to revelation in his scheme of epistemology. In a sense, he was much ahead of his time, considering that his work and life manifest a quest that fathomed deeply into all different branches of knowledge of his time, and he saw in the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle those truths and methods of demonstration of those truths which were directly relevant to and yet surpassed by the revelations in the Holy Koran. It may even be conjectured that if he were acquainted with the truths and insights that we can discover in the Veda and Upanishads as much as he found them in Plato and Aristotle, he would have been led to formulate a greater synthesis of the East and the West than what he had accomplished. For it can be suggested that Plato's philosophy, which is at the root of Aristotle's philosophy was greatly influenced by Orphic beliefs, and as Burnet has pointed out, there is a striking similarity between Orphic beliefs and those prevalent in India at about the same time. Even now, when we visit the philosophy of Ibn Rushd, we find in that

philosophy a remarkable subtlety of exposition which demonstrates an attitude of under-standing as also a reverential sacredness which can be considered to be a salutary psychological gestalt that can pave the way not only for what we call today tolerance but even for com-prehensiveness in which each aspect of the truth and each strand of the truth find its proper place and value in a study of consciousness where totality and holism can flourish.

II

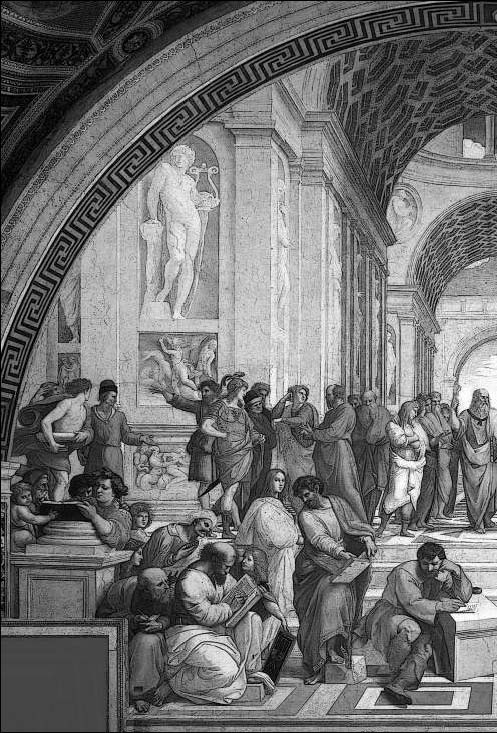

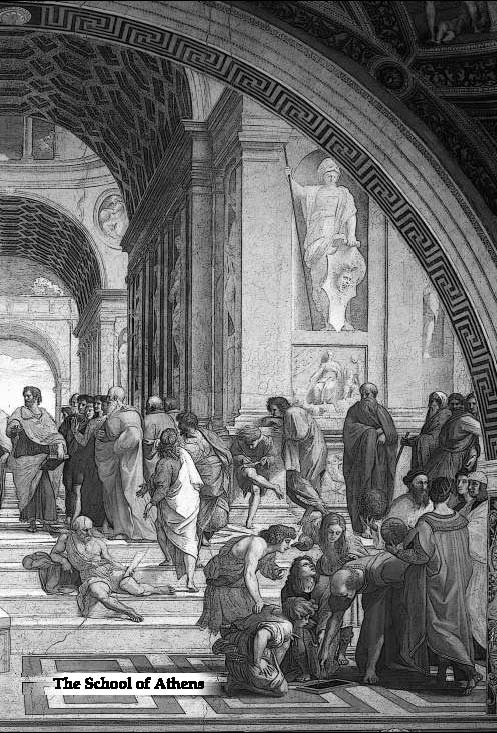

The most important contributions of Ibn Rushd were based upon his mastery over Platonic philosophy, Aristotelian philosophy and Neo-Platonic philosophy. He had, indeed, a more complete knowledge of Aristotelian works and analysed them carefully and more accurately than Al-Farabi and Ibn Sind, and he had indeed the highest admiration for the philosophy of Aristotle. But even when Aristotle seemed to have assumed that he had grasped the truth, Ibn Rushd had the courage to caution to

suggest that that assumption was not entirely justified. He maintained that while Aristotle comprehended the whole of the truth which human nature is capable of grasping, he did not possess what can be possessed by faith in revealed truth. He was quite clear that in those cases where philosophy is silent and where it cannot have access to the truth, instruction must come from the word of God.

It is instructive that the distinction that he made between what can be known through reason and what can be known through revelation does not lead Ibn Rushd to the kind of dogmatism which is often witnessed among theologians belonging to different faiths. Ibn Rushd developed a profound system of epistemology, in which we find striking influence of Aristotle but also of the tradition of revealed knowledge. He speaks of 'first material intellect', which had disposition to receive the intelligible that are in the forms of the imagination. But this intellect can be generated and can be destroyed, since the

imagination is inseparable from the corporeal structure. As distinguished from first material intellect, there is also, according to Ibn Rushd, the material intellect which is also called the intellect in potentia. Just as prime matter cannot be generated or destroyed even so the material intellect is eternal as pure potentiality. As pure potentiality, it must receive forms from active intellect or intellect in actu. According to Ibn Rushd, it is possible for man to apprehend the active intellect, the operation of which appre-hends or comprehends that which itself is eternal and which is not dependent for its existence on the act by which we conceive it. The objects of the first material intellect and of the material intellect or intellect in potentia are apprehended through the forms of imagination or the eternals which are only potentialities in prime matter. According to Ibn Rushd, man is able to transcend the limitations of the first material intellect as also of the material intellect and to participate in the active intellect in a state that is called conjunction (ittisala) or union (ittihada).

There is, according to Ibn Rushd, a distinction between the intellect and the soul. The intellect, the highest intellect, is absolutely free of matter; it represents the higher domain of the perception of the general or the abstract or of the universal forms which are reflected in matter and which are capable of being reflected in potential matter. The highest intellect is pure thought. The soul, even though it can possess the pure intellect, is the energy that animates Matter, and as such, far from being absolutely opposed to matter. It is, on the contrary, profoundly mixed up with and involved in it.

It appears that while knowledge of forms in their purity can be logically derived from the operations that can be discovered in the active intellect, and while the immortality of forms can be logically demonstrated, the existence of the soul and the immortality of the soul cannot through the same logical methods be demonstrated. The only point that can be made in logical terms is that forms in their purity or forms as found in matter do not explain the

totality of experience of the world and the mystery of the experience that each individual feels in his involvement with matter. This is the point at which one can rationally accept to turn to that knowledge that lies beyond intellect and which, one may legitimately argue, can be had from revelation. In that sense, there need not be any quarrel between the deliverances of reason and those of revelation. It appears that according to Ibn Rushd, arguments of a purely philosophical order do not force us to believe that individuality really exists, but they show that it is possible. This may be regarded as a philosophical introduction to the problem, and this pushes us to the point where one is enabled to leave it to revelation to settle the question. And this philosophical introduction is pushed to the point of revelation regarding the knowledge that the soul forms the body, and that, since it forms it, it cannot depend upon it. The important conclusion is that we cannot deduce the destruction of the soul from that of the body.

III

Philosophically, a distinction needs to be made between particulars and the individuals, even though in certain systems such a distinction does not obtain. In the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, a good deal of reflection is to be found in regard to the relationship between the universals and the particulars. The Platonic theory of Ideas or Forms is devoted to the determination of that relationship. The basic argument commences from the facts of similarities that are found in the world. In the attempt to explain similarities, by suggesting the existence of the universal or the existence of an ideal form, it has also been argued that particular things always partake of opposite characters. All particular sensible objects, so Plato contends, have a contradictory character. What is beautiful is also, in some respects ugly. Thus, they are intermediate between being and non-being, and are suitable as objects of opinion but not of knowledge. Plato points out that those who see the absolute and eternal and

immutable may be said to know, and not to have opinion only. According to the theory of ideas and forms, the word 'cat', means a certain ideal cat, the cat', created by God and unique. Particular cats partake the nature of the cat, more or less imperfectly. The cat is real; particular cats are reflections or copies and are only apparent. This theory was criticised by Aristotle and this criticism was anticipated by Plato himself as is evident from the Platonic dialogue Parmenides. Six arguments were raised, and it is worth mentioning them, since the Philosophy of Ibn Rushd is closely connected with Plato, Aristotle and Neo-Platonists. These arguments are:

1. Does the particular partake of the whole idea, or only of a part? If the former, one thing is in many places at once; if the latter, the idea is divisible, and thing which is a part of the smallness will be smaller than absolute smallness, which is absurd.

2. Secondly, when a particular partakes of an idea, the particular and the idea are similar;

therefore, there will have to be another idea, embracing both the particulars and the original idea. And this has to be ad infinitum. This is the same as Aristotle's argument of the third man.

3. Thirdly, ideas must not resemble the particulars that partake of them, if the argument of the third man is to be avoided. But if they do not resemble, how can ideas explain the particulars and their simil-arities?

4. Fourthly, to the suggestion that ideas are only thoughts, it is pointed out that thought must be of something.

5. Fifthly, ideas being absolute, and since our knowledge is not absolute, ideas, if there are any, must be unknown to us.

6. Finally, it has been argued in Parmenides that if God's knowledge is absolute, He will not know us, and therefore cannot rule us.

Aristotle, who advanced the argument of the third man, was led to maintain that the universals and the particulars are not

independent of each other. According to Aristotle, universal cannot exist by itself but only in particular things. However, Aristotle ultimately came to acknowledge that not everything has matter and that there are eternal things and these have no matter. The view that forms are substances, which exist independently of matter in which they are exemplified, seems to expose Aristotle to his own argument against Platonic ideas. It appears that although Aristotle saw the untenability of the Platonic theory of universals and particulars, he was ultimately led to Platonism. As Zeller points out, there is in Aristotle a want of clearness, and the final explanation of this want of clearness is to be found in the fact that he "had only half emancipated himself ... from Plato's tendency to hypostatise ideas."1

There is, thus, no satisfactory answer to the relationship between the universals and the

1. Aristotle, Vol. 1, p. 204, as quoted in Bertrand Russell, The History of Western Philosophy, p.179.

particulars. But both Plato and Aristotle speak of the soul, and while speaking of the soul, and even when it is admitted that souls are many, there does not seem to be a satisfactory discussion whether souls are particulars and whether there are any universals to explain similarities amongst the souls. On the other hand, if the soul is not a particular, and if it is not universal either, it is not clear as to how to describe the nature of the soul. At the same time, both Plato and Aristotle speak of the immortality of the soul, although their concepts of immortality are not identical. It would appear that souls would be best described as individuals as distinguished from particulars, and these individuals could be derived, not from forms or ideas or universals but from God. But at the same time, it may be admitted that the concept of God that one finds in Plato and Aristotle does not clarify whether God himself is unique or particular or universal or more than universal. This is an important question, and if we study the philosophy of Ibn Rushd against the background of this question, one

finds that his philosophy on this question is profounder than Plato, Aristotle or Platonism. And this may seem to be the result of his recourse to the revelation to which he had access in the Holy Koran.

According to Ibn Rushd, the world as a whole is a creation, but he does not admit creation ex nihilo. According to him, creation has its origin in God, but God as the cause of the world is not like the cause that we find in the world. God as the cause of the world is the cause not in time but as a cause of time as such, and therefore, not located in the series of time. Again, God is the creator of the world which is constantly changing, and therefore, creation is conceived as being renewed at every instance in a constantly changing world.

Ibn Rushd was greatly engrossed in the problem of origin of beings or with the origin of multiplicity. The basic question was how, God being one, multiplicity can emerge from him. According to Ibn Rushd, God is the single

power and from that power comes the first principle. The whole world results from it and all its parts are so ordered and connected that the whole, moved by the single energy, acts in concert. He underlines the Holy Koran's formulation that God creates, maintains and preserves the world, but he argues that it does not necessarily follow that, because this power penetrated into manifold beings, it is itself manifold. Multiplicity flows from the first principle, which is single itself but becomes manifold in the beings that participate in it. The beings that participate are individual souls, and this idea can become more understandable when we learn of the view of many Arabic philosophers who maintain that the soul resides in a subtle thing called celestial heat, in which are the souls that form the body. Some call this heat the natural celestial faculty; it is sometimes called the informing faculty. These souls form bodies, and it is, therefore, maintained that the souls do not depend on the bodies and the destruction of the bodies does not imply the destruction of the souls.

The souls are individuals and human life is meant for the process of souls' work on material life towards individualisation. The different-iating mark of the individuals as distinguished from particulars is that individuals have the capacity to hold in their possession the manifestations of matter, and imprints of universal ideas in matter, as also to posses the first material intellect, the material intellect and active intellect.

At this point, we come to Ibn Rushd's theory of resurrection. It was argued by Algazel that the school of philosophers denies resurrection. Ibn Rushd denies the charge and points out that the theory that denies resurrection is nowhere to be found among the members of the school of philosophers. According to Ibn Rushd, souls, after the death of the material bodies, will have in the other life, will have another kind of bodies. He maintains that that which will be resuscitated will be a representation of what is seen in this world, but it will not be the very thing in essentia. He argues that what has

perished cannot be born again, except in so far as it is individualised. Existence, he pointed out, can be bestowed only on the semblance of what has perished, not on the object which has perished in its identity. Ibn Rushd contented that future exists as a kind of generation more elevated than that of actual existence and constitutes a more excellent order than the order of this world.

It will be seen that Ibn Rushd derived his concept of the oneness of God, of God as a transcendental cause of the world, his concept of the world as a perpetual creation and God's continuous presence in the world, as his concept of the soul, of the immortality and of the resurrection of the soul from the revelations to which he had access in the Holy Koran. Ibn Rushd also answered the question of God's knowledge and of the affairs of the world in the light of the Holy Koran. There was an argument that the first principle comprehends only its own essence. From this argument a conclusion was sought to be derived that God is ignorant of

the whole world and that God does not know his own creation. Ibn Rushd does not agree with this contention. He maintains that God's knowledge is of a kind quite different from the knowledge that human beings have. It may be said that God does not know the world and the affairs of the world in the way in which we know them, but he does know them in a manner that is peculiar to Him. Ibn Rushd went farther to contend that it is impossible to say that the Divine is general and that there is no particularity in his knowledge. Generality and particularity are according to him, modes of human knowledge, and they refer to beings who are causes of human knowledge but cannot be the cause of God's knowledge. Again, we cannot, according to Ibn Rushd, admit that the knowledge of God depends on beings, for then the less will be necessary for more perfect. It stands to reason, therefore, that God conceives things in a higher order of existence than that in which we know them.

IV

It is impossible in this very brief exposition to convey the outstanding greatness of Ibn Rushd as a man and as a philosopher, and to present the greatness of the influence that Ibn Rushd exercised for several centuries. The works of Ibn Rushd were translated into Latin early in 13th century by Michael Scott, and his influence in Europe was very great, not only on the scholastics, but also on a large body of thinkers. Many professional philosophers were his admirers even at the University of Paris. Although in his own time, Ibn Rushd was misunderstood, he came to be defended by several philosophers against the charge of unorthodoxy. Ibn Rushd improved the Arabic interpretation of Aristotle, and it is true that he gave to Aristotle an exceptional kind of reverence. But an impartial study of Ibn Rushd would convince us that like most of the later Mohammedan philosophers, he was a believer, although not rigidly orthodox.

Religions are often misunderstood on account of their interpreters who are averse to philosophical thought. But when we take into account various modes of knowledge, including philosophy, interpreters like Ibn Rushd should be regarded as great bridge builders between religion and philosophy, between religions themselves, and between various modes of knowledge, even those which go beyond philosophical knowledge and which oblige us to study revelations with reverence that they deserve.

Related Books

- Beyond religion: Towards Synthesis, Harmony and Integral Spirituality

- Bondage, Liberation and Perfection

- Contemporary Crisis of Humanity and Search for its Solutions

- Ibn Rushd

- Integral Yoga of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother

- Party System and Values of Honesty and Efficiency

- Philosophical Notes on Schopenhauer and Indian Philosophy

- Problem of Knowledge - Problem of Causality, Change and Time

- Socrates, Plato and Aristotle

- Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy of Education

- Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy of Evolution

- Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy of Human Development and Contemporary Crisis

- Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy of Nationalism and Internationalism

- Sri Aurobindo's Philosophy of the Ideal of Human Unity

- The Human Journey The Vedic View

- The Veda in the Light of Sri Aurobindo

- Towards Applied Philosophy

- Towards Universal Fraternity

- Vedic Ideals of Education

- What is Yoga

- Yoga, Consciousness and Human Fulfillment