Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist - The Story of Abraham Lincoln - Chapter I

The Story of Abraham Lincoln

Young Abrahma on his father's farm

Chapter I

The Birth

February 12, 1809. Deep in the woods of Kentucky, in a little log cabin, on a cold winter morning, the sun rose to herald the birth of a baby born to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks. He was named Abraham Lincoln, after his grandfather, who was attacked and killed by Indians while labouring in the forest to develop a farm. Lincoln's father, Thomas, was only six years old then (See Map p. X-B).

Though Thomas' family had at one time owned slaves, his father despised slavery. And that became one of the reasons for their family's migration from Kentucky. In 1816, they travelled with horses piled high with all their meager belongings, cutting and hewing through thick woods across the Ohio River, to the free state of Indiana, a wild region where slavery was not permitted and land was cheap. Abraham was seven years old.

Life was not easy. It was hard work developing a farm, clearing the forest, hoeing the fields and splitting wood to build fences and cabins and furniture. His father would take him along to help in the fields sowing corn and chopping wood. He was so good with the axe, that in his youth, his father often hired him out in

the neighbourhood. Abraham was large for his age, and he later recalled working the axe almost constantly till the age of twenty-three, except of course, in plowing and harvesting seasons.

Lincoln referred to his parents as coming from 'undistinguished families'. He nearly drowned once but a boy in his neighbourhood saved him; when he was ten, a horse kicked him in the head and nearly killed him.

They were religious people and in his childhood his mother would often recite passages to him and his sister from the bible. His parents were not literate but they wanted their children to get an education. After they finished their work in the fields, Abraham and his sister would embark on a long hike through woods and across streams to a school. He wrote in a sketch of himself:

"... There were some schools, so called; but no qualification was ever required of a teacher, beyond the "readin, writin, and cipherin"1 to the Rule of Three. If a straggler supposed to understand Latin happened to sojourn in the neighborhood, he was looked upon as a wizard. There was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education... I have not been to school since. The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity..."2

He once said that it would barely total a whole year if all the days of schooling were put together. 'He was... never inside of a college or academy building till since he had a law-license...'3

"The Life of Washington, while it gave to him a lofty example of patriotism, incidentally conveyed to his mind a

- calculating

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), letter to Jesse W. Fell, Enclosing Autobiography, Dec. 20th, 1859, p. 107

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Autobiography written for campaign, June 1860, p. 162

general knowledge of American history; and the Life of Henry Clay spoke to him of a living man who had risen to political and professional eminence from circumstances almost as humble as his own.... Abraham must have been very young when he read Weems' Life of Washington... Alluding to his early reading of this book, he says: "I remember all the accounts there given of the battle fields and struggles for the liberties of the country, and none fixed themselves upon my imagination so deeply as the struggle here at Trenton, New Jersey... I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that those men struggled for." Even at this age, he was not only an interested reader of the story, but a student of motives."1

At the age of ten, Lincoln's mother died. Seeing the sorry state of his household, Thomas married an old friend Sarah Bush Johnson, who was a widow with three children. She was a kind woman and Abraham bonded with her immediately. She encouraged him to learn and his first books of stories were part of the few possessions she brought with her to their home. She passed on to him her sense of humour, which later became legendary and a part of every sphere of his life:

"What he learned and stowed away was well-defined in his own mind, repeated over and over again till it was so defined and fixed firmly and permanently in his memory... He was dutiful to me always, he loved me truly I think.

I had a son John who was raised with Abe... but I must say... that Abe was the best boy I ever saw or ever expect to see."2

When Lincoln was a lawyer, he decided to buy a piece of land

- Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J. G. Holland, p. 31

- Herndon's Informants: Letters, Interviews, and Statements About Abraham Lincoln, Sarah Bush Lincoln's interview, September, 1865, p. 108

for his step mother; his friend suggested that he could arrange to get the property transferred to Lincoln's name after her death, to which he replied, 'I shall do no such thing. It is a poor return, at best, for all the good woman's devotion and fidelity to me, and there is not going to be any halfway business about it!'1

His parents joined the local Baptist church; he would stand atop a tree stump and rattle off the sermons he had heard and make his friends laugh. This was, perhaps his initiation into speech making at which he later became very adept.

Lincoln was already six feet tall with angular looks and a lean frame by the time he reached the age of sixteen. All the hard work had made his body strong — he was good at athletics, —specially running and wrestling. Though he was friendly with many people he was not known to being close to anyone. In fact, with the passage of time, he grew further and further apart from his father.

He was very kind; finding a stray horse, which he recognized, he looked around for its rider. He found him lying on the ground drunk. Lincoln hauled him on his shoulder and took him to a house nearby, sent word to his father that he would not be returning home that night and looked after him through the night.

Older now, Lincoln ventured out to earn money. In his free time he had made a flatboat and could barely believe his eyes when two men paid him a dollar to ferry them across on it to a steamer ship on the Ohio River! 'The world seemed wider and fairer before me. I was a more hopeful and confident being from that time. '2

Abraham now looked forward to seeing the rest of the world; he wished to widen his horizons and meet new people outside of his neighbourhood. At the age of nineteen, he was a tall and strong six foot four inch towering youth. His neighbour hired him to take his cargo on a flatboat down the Ohio and

- The Heart Of Lincoln, By Wayne Whipple, p..35

- The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, by Francis Bickness Carpenter, p. 98

Young Abraham's love for books

Ferrying cargo on a flatboat down the Mississippi river.

Mississippi Rivers all the way to a sugar plantation near New Orleans to be sold. Lincoln had no previous experience about business transactions, was not familiar with the river, had never made such a trip before, but he was so well known for his ability and integrity that his employer entrusted him with not only his cargo but also his son on this voyage. And Lincoln proved that his trust was not misplaced; it was a difficult journey; handling the boat in changing currents and jutting banks was not easy. But it was not only the rivers that were dangerous, — while they were docked, a gang of seven slaves tried to leap on to the boat with the intent to plunder. One by one, Abraham and his fellow traveller knocked them off the boat into the river, chased the others and gave them a severe thrashing, then sailed off towards New Orleans.

New Orleans was very different from any town he had ever seen! The port was crowded with boats, the docks were packed with cargo being loaded and unloaded off them, and Abraham could hear a cacophony of sounds coming from the hundreds of people going about their business at the port. Lincoln witnessed a slave market for the first time in his life; families of slaves broken up, men and women lined up on opposite sides, buyers checking on them like livestock before making their final purchase. Abraham completed the sale of cargo, sold the flatboat and returned home.

In 1830, when Abraham was twenty-one years old, his father decided to move the family to Illinois, where the prairies were supposed to be much more fertile. They set out towards their new destination in ox driven wagons loaded with their humble belongings. It was a difficult journey of two hundred miles covered in fifteen days — driving the wagons through mud and rivers overflowing with rain. Abraham helped him build their new cabin, split wood to make furniture for their home and fences to enclose their farm. After he had assisted his father in building their homestead and sowing corn in the fields, he decided to set out on his own.

Growing His Wings

In summer he tilled the soil and in winter he chopped wood and split logs to make fences — anything to keep himself clothed. There is a story that he made a bargain with a woman that he would split enough pieces of rail for her in return for a pair of trousers!

Having earned a good reputation, he was hired again to work on a ferry. The boat was launched and they set sail towards New Orleans. But as they neared New Salem, their boat got stuck at a milldam and they struggled to save it from sinking. Abraham tried to free the boat but failing to do so, he directed the crew to unload some of the cargo on to the shore to shift the balance to the stern. He then went ashore, hired a hand drill from a shop and plied a hole in the bow to allow the water to drain out.

So impressed was his employer by Abraham's navigational skills and his honesty that he decided to utilize Abraham's services to manage a general store and mill. In July 1831, twenty-two year old Abraham moved to New Salem; the store was not ready so Abraham boarded at a tavern and did odd jobs to keep body and soul together — Mentor Graham, the schoolmaster at New Salem, and clerk for the elections, hired him as his assistant for the elections of Governor and members of Congress. However innocuous, this was the beginning of his entry into politics.

Finding work in New Salem was easy for Lincoln, — be it splitting rails, repairing milldams, husking corn for farmers or working at the store; the locals found him to be hardworking, always willing to work for anyone who needed help. James Short, one of his first friends in New Salem thought he was the only man, who could husk twice the corn than he could. Abraham was funny, loved telling stories and made friends easily; he had never lived anywhere that had so many people — almost a hundred.

The store opened and Lincoln moved in. He still could not

afford a place of his own; he slept in a back room of the store along with William Green, a clerk who helped him in the store. It was during this time that Abraham was nicknamed Honest Abe — he would go miles to return a few cents that had been overpaid by clients or to deliver supplies that had been under weighed by error during a purchase.

Another trait of his personality emerged during his stay in New Salem. While showing goods to a few ladies in his store, a bully came in and began using abusive language. Abraham asked him not to indulge in such behavior in the presence of ladies but it was to no avail. Abraham then followed him outside and without a shred of anger, beat him up. He then fetched water and washed his opponent's face and did all he could to reduce his pain! The bully became his life long friend and a better man under his influence.

There was a gang at New Salem — the Clary's Grove Boys —who prided themselves for their physical courage and skill and would challenge all newcomers to a race or a bout of wrestling to check them out. Abraham too had to pass that test. Seeing his large frame and strong body, their leader, Jack Armstrong, decided to be his opponent. It is debated as to who won the bout but either way, the boys found in Abraham an adversary worthy of respect and admiration and invited him to become a part of their gang. Soon, his honesty and fair play made them select him to judge races and other contests. He became popular not only for his physical capacity but also his witty jokes. Abraham's friendship would be one that would serve Armstrong well later in his life.

Abraham did not share their indulgence in alcohol or tobacco. He was not a prude as to shun these vices or impose his aversion on others, — he found that alcohol left him 'flabby and undone'.

Life in New Salem proved to be a great learning experience for Abraham. It was a welcome change to be among lettered people. In New Salem Abraham found his first set of friends who were men of accomplishment. Mentor Graham, a schoolteacher,

took it upon himself to further his education; he encouraged his love for poetry and oratory; he would lend Abraham his book on English grammar and observed that no one could match the speed at which Lincoln acquired its rules.

Jack Kelso, the village genius, introduced Lincoln to the beauty of Shakespeare, Burns and Byron, — from whose works he quoted from time to time throughout his life. All these he studied while he worked at the general store. He regretted `his want of education, and' did what he could 'to supply the want...'1

James Rutledge, who started the New Salem Debating Society, lent him books and encouraged him to participate in debates. One such book contained Daniel Webster's speech of 1830 criticizing the theory of nullification2. He was highly impressed. In time his confidence grew as he debated passionately on topics close to his heart.

Bowling Green, a prominent county commissioner and judge looked upon Lincoln as a son and fostered his career as a lawyer. Green would ask him to summarise cases and Lincoln often attended the local court to witness the hearings. Impressed by young Lincoln's logic, he encouraged him to write legal documents for him. Later, Lincoln also appeared as witness and defendant in lawsuits where he was hired by creditors to collect their debts. In fact, it is said that during his deep depression in 1835 after the death of Anne Rutledge, his first love, Green and his wife took him to their log cabin and nurtured him till he overcame his grief.

Lincoln was known to be shy in the company of single women, perhaps he was afraid of rejection in love; but he was very comfortable among married women, who mothered him — preparing hot meals for him, repairing his ripped pants or simply giving him advice.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Autobiography Written for Campaign, June 1860, p. 162

- Calhoun's theory of nullification defended state rights to reject federal laws in case they were in conflict with the interest of the state.

In 1832, his friends, especially James Rutledge, aware of Lincoln's popularity, intelligence, proficiency in debating, and knowledge of the Sangamon River, encouraged him to run for State Legislature. They felt he would help serve the interests of their town's economy. Abraham announced his candidacy through a political announcement; he opposed the development of a local railway project due to high costs, he supported navigational improvements on the river, promoted education for all, made demands for a National Bank and for high protective tariffs to protect indigenous industries.

Two events took place that changed Abraham's life — the store he worked for ran out of business and the Black Hawk War1 began. Jobless, in 1832, he and his friends, eager to take part in the war, volunteered for service. Two men were nominated as captains, — Lincoln and one William Kirkpatrick. Three quarter of the volunteers voted for Lincoln and the remaining one fourth who had chosen Kirkpatrick changed sides and crossed over to Lincoln on seeing themselves in the minority. Lincoln later acknowledged, 'I was elected a Captain of Volunteers — a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since.'2 Kirkpatrick had been a former employer who had cheated Lincoln of his wages, but the latter being above any ill-will, did not retaliate.

Lincoln's men grew to respect and idolize him. When an Indian surrendered at their camp, his men wanted to kill him but Lincoln stopped them. When called a coward, rising to his full height he said, 'If any man thinks I am a coward, let him test me', allowing them to generously chose a weapon to compensate for his larger height and weight!

Lincoln did not get an opportunity to engage in any combat in the Black Hawk War. He returned to New Salem just two weeks prior to the elections but did his best to visit as many

- The brief conflict in 1832 between the United States and Native Americans, when the latter entered into Illinois to settle down.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), letter to Jesse W. Fell, Enclosing Autobiography, Dec. 20th 1859, p. 107

voters as he could to campaign. He went from door to door, helping people in their work. Wherever he would see a group of people he would join in and begin. to speak. During one of his speeches, he saw two men getting into a fight. He saw that one of them was his friend who was being roughed up. He broke off, descended from the stage, hauled up the offender and threw him several feet away on the ground. Then, he went back on stage and resumed his speech as though nothing had happened. His military career (though short) and his popularity with the soldiers who served him and campaigned for him, no doubt helped him in his precinct where most people irrespective of their political leanings, voted for him, but Illinois being predominantly a Democratic state, he lost the general vote in the state. He remarked, `... ran for the Legislature the same year ( 1832) and was beaten — the only time I have been beaten by the people.'1 He was ambitious and it seems he had reached a certain inner decisiveness for the future.

Without a job and nowhere to go, he was anxious to stay at New Salem with his friends. He thought of studying law, but realized that without a better education he would not succeed. He contemplated on the idea of becoming a black smith too. He finally borrowed money from his friend William Greene, went into partnership with his friend Berry and bought over a general store. But, Berry was busy drinking and loafing and Lincoln, spent most of his time reading or telling stories, as a result of which, the store failed. He now owed Greene a lot of money; Lincoln called it the 'National Debt', and though it took him fifteen years, living true to his name, Honest Abe, he did pay back, not only the principle amount but also the enormous amount of accumulated interest.

Lincoln was in dire need of a job; his friends helped him out again and he became Postmaster of New Salem in 1833. He liked his new occupation; it gave him plenty of time and opportunity

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), letter to Jesse W Fell, Enclosing Autobiography, Dec. 20th 1859, p. 107

to read newspapers. And not one to be confined to an office, he tucked letters in his stovepipe hat and went around town delivering letters to the townsfolk. But he needed to make more money; with Mentor Graham's help, he was hired by the County surveyor as an assistant to survey land in the vicinity of New Salem. Lincoln knew nothing of this trade, but determined to succeed, he bought a chain and compass, borrowed a book from his employer and set about once again to add to his growing set of skills. His wages helped feed both his body and his mind — he bought books and read constantly to improve his education. In 1835, Berry, his erstwhile partner in the store died, burdening Lincoln with his portion of the debt payable to Greene. It is said that his chain and compass were attached and sold to pay off part of the debt, but his friend James Short bought and returned them to Lincoln; enabling him to resume his duties once again. He was good at his job; he surveyed the town of Petersburg and territory next to it — politically too it was good for him, more and more people around New Salem got to know him.

Fledgling Flight

Up until now, Lincoln lived a life that was difficult, a personal struggle to keep body and soul together with an unflinching decision to educate himself despite endless hardships. His drive to learn as many trades as possible, an indefatigable aspiration to exceed pushed him to expand his mind and lead to a gradual development of his faculties. Determination and cheerfulness he knew, for it was these qualities that had fostered him through his difficult days. It was time to step into the public life and test his skills of oratory and ingenuity, courage and patience.

Lincoln was ambitious; he decided to stand for the Illinois Legislature elections again in 1834. His friends helped him immensely out of personal regard for him. Lincoln was vast and

friendly in his mind and heart — a quality that would serve him well throughout his tests in time and circumstance.

Though defeated the previous time, he knew he was more widely known now, as his work as surveyor had taken him outside his town to various places. It is said that on the onset of his campaign, he sold his chain and compass and bought a horse to reach out to as many people as possible. As soon as it was over, he sold the horse and reclaimed his instruments; he would be unable to make a living without them. He visited people in farms and helped them, went to all types of social gathering — be it dances, wrestling matches, debates or other events. He had been honing his skills at giving speeches on the persuasion of his friends. But he did not talk much about his political objectives; people were divided in their political leanings — townsfolk were more in favour of Whigs1 while farm folk favoured the Democrats2.

Major Stuart, an acquaintance from the war, impressed with Lincoln's canvassing, advised him to study law and promised to lend him his books. At the end of the canvassing, he went to Springfield to borrow them, returned home and began the study of law in earnest. When he ran out of money he would go on a surveying tour to earn enough to keep him going. His friends remember him sitting under an oak tree immersed in his books to the exclusion of all else — he had found his pursuit in life and was determined to master it.

His earnest efforts at campaigning paid off — he received the largest number of votes and in August 1834, he was elected a legislator of Illinois as a member of the Whig Party. He borrowed money to buy a suit and plodded about a hundred miles all the way to Vandalia, the capital of Illinois, marking the start of his public life. Since he was new to the world of politics, he spoke little and listened attentively to the older, more seasoned

- The Whig Party, in the United States, was concerned with promoting internal improvements, such as roads, canals, railroads, deepening of rivers, etc. They were popular in the West which, being isolated, was in need of markets.

- Democrats wanted a weak federal government, believed in states' rights, agrarian interests (especially Southern planters) and strict adherence to the Constitution; it opposed a national bank.

speakers in the house.

"The homely man was majestic, the plain, good-natured face was full of expression, the long, bent figure was straight as an arrow, and the kind and dreamy eyes flashed with the fire of true inspiration. His reputation was made, and from that day to the day of his death, he was recognized in Illinois as one of the most powerful orators in the state."1

His second term in the Legislature in 1836 found him in the company of some of the brightest men of Illinois; Lincoln was considered by now as one of the leaders in the General Assembly.

It was here that Lincoln met Stephen Douglas, an attorney, only twenty-four, the youngest legislator in that house. They `marked out the course in which they were to walk — one to disappointment and a grave of unsatisfied hopes and baffled ambitions, the other to the realization of his highest dreams of achievement and renown, and a martyrdom that crowns his memory with an undying glory:2 And it was here that they began their political fencing; on various issues, little knowing that it was to lead to a set of debates that would lay the foundations for liberty in America.

Lincoln learned the art of political bargaining. Stephen Douglas was pushing a multi-million dollar bond to improve the transport network in Illinois but did not support the shift of capital from Vandalia to Springfield. Lincoln shrewdly secured the shift to Springfield by tying one to the other; the Whigs from his county would accept the resolution for internal improvements only if Springfield was voted as the New Capital of Illinois.

- Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J.G. Holland, p. 67

- Ibid., p. 69

The Nat Turner1 slave revolt in Virginia in 1831 provoked stronger slave laws. The slave states felt that the abolitionists in the north were causing these slave rebellions. So, the Southern states began appealing to .Governors of Northern states like Illinois, for their support in protesting against the growth of the abolitionists. Illinois bordered two slave states, Missouri and Kentucky and was keen to be on friendly terms with them. Both the Democrats and the Whigs were against the abolitionists. Sentiments were such that anyone opposing a proslavery proposition was branded an abolitionist. When the Democrats proposed the following proslavery resolution, it was voted for by all but five members; Lincoln was one of them. It was brave of him; being branded as an abolitionist could have ruined his political career. It stated that the General Assembly highly disapproved of the formation of abolition societies and their doctrines; that the constitution gives the slave-holding States the right to slaves as property and that they cannot be deprived of that right without their consent and that the federal government cannot abolish slavery in the District of Columbia against the consent of its citizens.

Six weeks later Lincoln and Dan Stone issued a written protest that stated that they believe that a) The institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy; but that the broadcast of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils; b) That the Congress of the United States has no power under the constitution to interfere with the institution of slavery in the different states; c) They believe that the Congress of the United States has the power under the Constitution to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia; but that that power ought not to be exercised unless at the request of the people of said District; d) The difference between these opinions and those

1. In 1831, Nat Turner, a slave, led a rebellion in Virginia and killed some sixty white men, women, and children. He and 16 of his conspirators were captured and executed. To warn other slaves, blacks were randomly killed, many were beheaded and their heads left along the roads to warn others. After this incident, planters tightened their grip on slavery.

contained in the said resolutions is their reason for entering this protest.1

He needn't have made this written protest; but it was what he believed to be the truth. And he had the courage to proclaim it. Though he believed in the sentiments of the abolitionists, he did not believe in their methods. As he said later, A drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall.'2 When the session ended, Lincoln returned back a hundred miles. It was clear that in the field of politics, with his study of Law, and the courage of his convictions, Lincoln had found his feet.

New Skies

Lincoln had received his law license in 1836; he moved to Springfield, where he could see the possibility for both his legal and political career — he was already popular there as a legislator since he had been instrumental in the removal of the capital to Springfield, and Stuart had promised him a partnership in his law firm.

So, mid 1837, astride a borrowed horse, with all his earthly belongings in his saddlebags, he set out for Springfield. There, Lincoln met Joshua Speed, a merchant in his general store, who would become his most intimate and lifelong friend. Unable to afford the price of a single bed, he requested a loan promising to pay back once his career as a lawyer took off, but warning him that if it didn't, he would never be able to pay it back. Seeing Abraham's sad expression, Joshua offered him free lodgings above his general store, an offer Lincoln promptly took up and settled in immediately, and the two shared a room and bed for the next three and a half years.

- Adapted from Lincoln's original resolution.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings ( 1832-1858) , Address to the Washington Temperance Society of Springfield, Ill., 1842, p. 83

Though Springfield was more cosmopolitan with better homes than New Salem, without money or friends he felt lonely and found the town dull. However, Speed and his acquaintances helped Lincoln get familiar with his new town. Lincoln loved telling stories and jokes and often read poems but sometimes he would prefer to be by himself. Speed recalls that people sought him out; he did not seek their company.

He began to practice law with Stuart, working independently for the last four years when Stuart, on being elected to the Congress, left Springfield in 1838. His next three years were spent 'riding the 8th Judicial Circuit'1 (see Map p. XIII), handling debt-related cases relating to the Panic of 18372. His reputation as one of the best lawyers in Illinois was secured during this period.

His legal education was limited compared to other lawyers who came from educated backgrounds; he made up for that shortcoming by being very thorough in his investigations. He made a habit of arguing against himself; this practice gave the impression that he was rather slow at coming to conclusions but in actual fact it made him sure of the position he would be taking during proceedings.

He studied his cases meticulously and if he found one to be weak, he would advise the applicant to dismiss the case. At times when he found out that his client had lied to him, he would lose interest in that case and his effort henceforth would be only per

- Each state is divided into districts containing a number of counties. A single judge appointed for each district rode the circuit along with distinguished lawyers, holding court in each county. The circuit was covered on horseback or in a gig.

- President Andrew Jackson's policies had led to the destruction of the Second Bank of United States. Federal reserves had been moved from the Second Bank to some smaller state banks. But credit policies of these state banks were reckless; they loaned paper money indiscriminately, which they printed in excess of their reserves of gold and silver. To arrest this trend, Jackson ordered that federal land could be bought only on payment of gold or silver. People ran to banks to exchange their paper money for these precious metals, but the banks began to refuse them due to sufficient reserve; many banks crashed, thousands of people lost their land; loans dried up, businesses and civic projects collapsed, purchases went down, all this led to severe unemployment which resulted in people going hungry.

functionary, or he would give it up half way through the proceedings. He truly believed in the establishment of justice, —there was a spontaneous dislike for immorality and wrongdoing in his mind and heart. At one time when he found out that he was defending a case that was on the wrong side of justice, he informed his partner that he was withdrawing from it. His partner, however, continued to defend their client. Much to Lincoln's surprise, the verdict was in his favour, but he refused the nine hundred dollars that was paid as fee!

"In presenting a case to a jury, he invariably presented both sides of it.... His fairness was not only apparent but real... He would stand before a jury and yield point after point ... so that, sometimes, his clients trembled with apprehension; and then, after he had given his opponent all he claimed, and more than he had dared to claim, he would state his own side of the case with such power and clearness that that which had seemed strong against him was reduced to weakness.... Every juror was made to feel that Mr. Lincoln was an absolute aid to him in arriving at an intelligent and impartial verdict.... The testimony of the lawyers who were obliged to try cases with him is that he was "a hard man to meet."1

He studied the backgrounds of his jury as well as he studied the elements of his cases. If they were rural folk, he would use simple terms and examples to ensure that they understood his point of view.

A funny yet heartfelt anecdote reflects again upon Lincoln's kindness. During one of these travels from one county to the other, Lincoln came upon a pig struggling to extricate himself from the mud. Lincoln looked at his somewhat new clothes and rode on, ignoring the poor beast; but two miles later found that the thought of the struggling animal was distressing him — he

1. Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J. G. Holland, p. 79

turned around and went back to rescue the beast. On analyzing his actions he came to the conclusion that it was not for the sake of the pig but for his own peace of mind that he had rescued it!

Lincoln's wit and humour were evident to all who were acquainted with him. Like a child he laughed at the subtlest of incidents and took delight in the simplest of things. But there were times when he would feel oppressed by the problems of his life and those of humanity.

"At one time, while riding the circuit with a friend, he entered into an exposition of his feelings, touching what seemed to him the growing corruption of the world, in politics and morals. "Oh how hard it is," he exclaimed, "to die, and not to be able to leave the world any better for one's little life in it!" Here was a key to one cause of his depression, and an index to his aspirations."1

Lincoln was an extremely caring man; at the end of a hard day at court, instead of resting at the local inn with his colleagues, he made it a point to visit and with great humility, board with his poor and long lost cousins, aunts and uncles who lived in the town that he was riding through. He would listen to their story and if needed help them financially. He was wide in his being and a friend to all.

He was honest in all his dealings; in case he took up some new cases on the circuit that were not entered in the office in Springfield, he made it a point to divide the fee he received after each case, putting aside for his partner the sum due to him, duly labeled with full details.

Given his aspirations for a political career, Lincoln immersed himself into politics to advance the Whig party. He understood the economic situation in Illinois well — including the involvement of politicians in corrupt land deals. On occasions he was given to reckless tactics, though never without just cause.

1. Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J. G. Holland, p. 83

Through the Sangamo Journal, he accused a Democrat congressman of acquiring land belonging to original settlers through dubious means. Despite these public accusations, the Democrat won by a great majority and Lincoln faced flak for his role in mud slinging.

Lincoln was reelected to Illinois General Assembly in 1838 and 1840 for a third and fourth term; during both terms he was nominated as speaker by the Whig party but failed in getting majority votes. In 1838, referring to the death of the Illinois abolitionist and editor Elijah P. Lovejoy, who was killed saving his printing press from a proslavery mob, Lincoln delivered a carefully worded speech to young men at the Springfield Lyceum, highlighting the dangers of using violence in a democracy:

"I do not mean to say, that the scenes of the revolution are now or ever will be entirely forgotten... They were the pillars of the temple of liberty... Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense. Let those materials be moulded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws... "1

He canvassed for Stuart, his law partner for congress elections for which he again locked horns with the Democrat candidate Stephen Douglas over the issue of national banks. He played a prominent role in the debates in the legislature but was in the minority. In a desperate attempt to save the state bank of Illinois from closure by the Democrats, Lincoln with two other Whigs jumped out of the ground floor window to prevent a quorum. However, the counting had already been done, and they were called back, and the death knell for the bank was sounded. This

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Address to Young Men's Lyceum at Springfield, January 27th 1838, pp. 35-36

tactic provoked derisive comments in the Democrat press. His main aim was now to focus on the Whigs winning the next Presidential election. Chosen as the presidential elector by Whigs, he canvassed actively for Harrison who won the 1940 elections.

The issue of slavery continued to pain him, as is evident in his letter to Joshua Speed:

"I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down and caught... but I bite my lip and keep quiet. In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip. There were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border. It is hardly fair for you to assume, that I have no interest in a thing, which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable. You ought rather to appreciate how much the great body of the Northern people do crucify their feelings, in order to maintain their loyalty to the constitution and the Union."1

He was torn between his moral stand against slavery and his loyalty to the constitution of America that legalized the right of the Americans to keep slaves. The passage of time would witness his efforts in the legislature and the congress to put an end to slavery in a staggered manner without violating the constitutional rights of the people.

Unable to handle his career as a politician and the law practice all by himself, he terminated his partnership with Stuart in 1841 and began another with Stephen Logan, one of the ablest and well read lawyers in Illinois. He watched Logan in court as he stated his case, saw how he investigated them, and honed his skills even further as a lawyer. In 1841, he won a case in defense

1. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 2, To Joshua F. Speed, Springfield, Aug. 24th 1855, p. 320

of a slave owner in Illinois.

Though the people urged him again, Lincoln refused a seat in the legislature in the 1842 elections. He was keen to put his financial condition in order and felt he ought to devote more time to his cases.

To Build A Nest

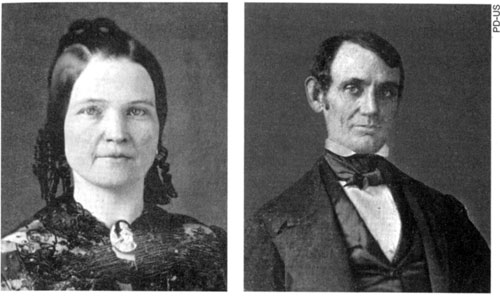

A few months after he arrived in Springfield, Lincoln met Mary Todd. She belonged to a wealthy family from Kentucky that kept slaves. She was well educated, could speak French, loved fancy clothes and parties, — diametrically opposite to the Lincoln of humble beginnings, opposed to slavery, self taught, still a bit rough around the edges, despite his political and legal exposure to men of education. They came from different worlds.

She came to Springfield to live with her elder sister and brother-in-law. Her beauty and charm attracted many a suitor, — Stephen Douglas, Lincoln's debating rival being one of them. But Mary was attracted to Lincoln; they shared a common love for poetry and politics. They were both prone to mood swings. They both hailed from Kentucky. Henry Clay, who influenced Lincoln's political views, was a regular visitor at her father's house in Kentucky. She saw the potential in Lincoln; he was quite vocal about his ambitions, — he had grown as a politician and a lawyer and there was promise of a great future. Despite their differences in society and class, they fell in love. Mary's family disapproved of Lincoln, considering Mary's higher station in life. Sensitive to the disapproval and unable to handle close relationships in his life, he broke off the engagement. Instead of feeling relief, he was miserable. Around the same time, his best friend Speed moved to Kentucky, — just when he needed his friend the most. He was distraught. He wrote to Stuart about his agony, am now the most miserable man living. If what I feel were equally dis-

Left : Mary Todd Lincoln (1846 or 1847), and right : Lincoln in Springfield at the same time

Left : Mary Todd Lincoln (1846 or 1847), and right : Lincoln in Springfield at the same time

tributed to the whole human family, there would not be one cheerful face on the earth.'1 Knowing of his tendency to go into depression, his friends were worried that he might end his life. He finally decided to visit Speed in Kentucky. This togetherness bore fruit, — his confidence in himself and his love was restored and he returned to Springfield happy. In fact, Lincoln too convinced Speed to marry the love of his life, Fanny.

Mary had written to Lincoln that she would wait for him to change his mind. A year later, they began courting again and finally in 1842, at thirty-three years of age, Lincoln wed Mary, ten years his junior. Though later Mary became impulsive and would be prone to hysterical behavior, Lincoln would always support her and care for her in times of agony. Mary admired him and depended on him emotionally. A deep love would bind them to each other till the end.

He could not as yet afford a house; but they enjoyed their

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Letter to John Stuart, January 20th 1841, p. 69

blissful union at the local tavern where they boarded at four dollars a week. He missed his friend Speed tremendously; he often wrote to him of his political affairs, joys and sorrows, and Speed would mentor him. In 1843, he was disappointed on not being nominated for congress by the Whigs and it added insult to injury when his Party asked him to help Baker, his opponent, during the canvassing. In a subsequent letter he acknowledged that Speed was right in advising him to support his Party nominee.

And not only did he support Baker politically but also protected his person from physical harm. During his speech, some ruffians threatened to take Baker off the stage; Lincoln who was listening to his speech immediately came on stage and in a calm but firm voice, spoke of fair play and finally quieted the bullies with threats. What started as a fight for a seat in congress, terminated as an enduring friendship between Lincoln and Baker till the death of the latter.

His friendliness was not limited to only his dear friends, — he extended his heart to anyone who needed it. A client, on the verge of bankruptcy, gave him a promissory note in lieu of his fee. A few months later, when Lincoln met him, the poor man had also lost his hand in an accident. Seeing his plight and his embarrassment at not being able to pay his fee, Lincoln took out the promissory note and handed it back to his client. At that time it did not matter that he was having difficulty in meeting his own family expenses and could not afford to visit his friends.

In 1843, they were blessed with their first son, Robert. The fruits of his labour on the 8th Circuit were beginning to yield results. In a year's time, he managed to buy their first house, which would be their home for seventeen years.

Joys of his new domestic life, legal cases in courthouses and local political intrigues kept Lincoln busy for two years. His partnership with Logan came to an end in 1844, after which he set up his own firm and invited young William Herndon as a junior lawyer. 'Mr. Lincoln, you know I am too young, and I have no standing and no money; but if you are in earnest, there is nothing in this world that would make me so happy.' Though Herndon

was more educated than Lincoln, in all other respects he was his junior. Lincoln was like a father to Herndon; even when his drinking bouts caused embarrassment, Lincoln refrained from rebuking him. Their mutual respect and trust grew over time, "Billy and I never had the scratch of a pen between us; we just divide as we go along,' said Mr. Lincoln'.1

The presidential elections of 1844 gave him a new vigour; his idol Henry Clay, was the candidate of the Whig Party for the presidency and he poured all his energies into the canvassing.

Once again, as a candidate for Presidential elector, he campaigned in the state of Illinois and later in Indiana, giving a string of speeches. Despite all the effort, Clay lost; not only the overall election but also the state of Illinois that supported expansionist ideas; it was a defeat that brought gloom to all his admirers, and in no small measure to Lincoln. But the campaign lifted Lincoln to great heights politically; his efforts had fortified the Whig Party in Illinois considerably, and his fame as a mighty debater had been proven throughout the country. His speeches, based on substantial facts and unarguable logic, became legendary.

The defeat of Clay was disappointing and unexpected for Lincoln. He believed that Clay was superior to Polk2, and the policies of the Whigs far superior to those of the Democrats, who fought the election on the Manifest Destiny platform. He blamed the people for their error in judgment rather than a shortcoming in his demi-god, Clay. Disgusted by the popular vote of the people given to one so undeserving in his eyes, he decided to quit politics and devote himself to his profession.

But destiny would not allow him to quit; two years hence, he got an opportunity to hear Clay speak on the subject of gradual emancipation at a meeting in Kentucky. He found it rather disappointing; it had neither the spontaneity nor the spirit he had expected. His personal interview with Clay was as disappointing as his speech had been. Though Clay appeared kind

- Life on the Circuit, by Henry C. Whitney, p. 460

- Democratic Candidate, 1844 Presidential elections

and acknowledged his gratitude for his active support during the campaign, Lincoln found Clay's manner overbearing and to some extent condescending.

"It is quite possible that Mr. Lincoln needed to experience this disappointment... It was, perhaps, the only instance in his life in which he had given his whole heart to a man without knowing him... He was, certainly, from that time forward, more careful to look on all sides of a man, and on all sides of a subject, before yielding to either his devotion, than ever before."1

Wind Beneath His Wings

In 1846, he made a bid for Congress and succeeded in securing a nomination; given his honest reputation and capabilities, the Whigs must have been as keen to have him in Congress on their ticket, as he was to be there.

His was the only Whig seat that won from Illinois in the House of Representatives; he was elected by an enormous margin and received votes that outnumbered those received by Clay in 1844. His popularity in his own district was phenomenal. As in New Salem during the Legislature elections, it was clear that he received votes that crossed party lines, thanks to the faith he evoked in his fellow men for his sincere and honest nature and honourable character.

Lincoln moved to Washington with his family and made their home in a boarding house where other congressmen were residing as well. With so much political and legislative experience behind him, Lincoln was quite comfortable in the House of Representatives. Coincidently, Stephen Douglas, his Democratic

1. Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Josiah Gilbert Holland, page 96

opponent from Illinois, at that time sat in the Senate. Almost like an operatic performance, leading to a crescendo, these two young political opponents were working their way up on the notes of the political scale. Illinois being predominantly Democratic, Douglas had an easy edge over him in Illinois. But the fact that Lincoln was the only Whig Congressman from Illinois made him conspicuous amongst his peers in Congress.

Lincoln was keenly aware of the issues that stirred the House and divided the people. Three issues were central to Lincoln's participation in the Congress.

Though he had remained silent on his objection to the Mexican War (see Map p. XII A), and supported the funding for the war at the time of the election, Lincoln took the general Whig position in denouncing President Polk for waging a war on Mexico, which they termed was both unconstitutional and unnecessary. Polk, keen to justify the war and uphold himself before the people, had sent a message to the House asserting that Mexico had commenced the war 'by invading our territory and shedding the blood of our citizens on our own soil.'1 Lincoln took the floor of the House and made a powerful speech in the House confronting Polk's stand; he presented an elaborate paper called the 'spot resolution' demanding information about the exact spot on which Mexicans attacked American soldiers and shed their blood. He pointed out that Polk had transcended his executive powers, `... because the power of levying war is vested in

1. In Sept. 1845, President James K. Polk wanted to negotiate the disputed Texas border, settle U.S. claims against Mexico, and purchase New Mexico and California for up to $30 million. When his offer was snubbed by Mexico, he sent General Zachary Taylor with his troops to occupy the disputed area between the Nueces and the Rio Grande, and wanted to justify his aggression on grounds that Mexico refused to pay U.S. claims and refused to negotiate the purchase. However, he got word that Mexican troops had crossed the Rio Grande and killed 16 U.S. soldiers. He, therefore, changed his message that Mexico had 'invaded...' Though Congress approved the War, Whigs viewed Polk's motives as immoral greed and abolitionists saw the war as an attempt to extend slavery. Democrats, however, especially those in the Southwest, strongly supported the conflict.

Congress, and not in the President'1 It seems that Lincoln would later regret making this statement, since during his presidency, he would be extending the war powers of the executive.

During the second session of Congress, he tried to arrest the expansion of slavery by voting in support of the Wilmot Proviso2, which stated that all territory annexed after the Mexican War would be declared free soil.

Though Lincoln believed that slavery was morally wrong, he was controlled and held back by his obligation to the Constitution of the United States. In an effort to reduce slavery, he, in collaboration with Abolitionist congressman J. Giddings, proposed legislation for a gradual and compensated emancipation of slaves in the District of Columbia, subject to majority votes of its people. But his effort failed; Congress discarded his proposal, — abolitionists thought it was a very weak and conservative manner of dealing with the slavery issue, and the slaveholders felt threatened by such a radical approach.

Lincoln's opposition to the Mexican War was considered anti-expansionist and was not received well in Illinois; they felt that Lincoln was misrepresenting their state in Congress. Democratic newspapers declared that 'spotty Lincoln' had committed political suicide. Herndon had tried to help Lincoln, both legally and politically:

"I wrote to him on the subject again and again and tried to induce him to silence, if nothing else; but his sense of justice and his courage made him speak, utter his thoughts, as to the war with Mexico... When Lincoln returned home from Congress in 1849, he was a politically dead and buried man; he wanted to run for Congress again, but

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Autobiography Written for Campaign, p, 166

- Mexico lost the War, a peace treaty was signed in which Mexico ceded all the territory now included in the states of New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, California, Texas, and western Colorado for $15 million. In August 1846, Representative David Wilmot of Pennsylvania tried to add an amendment to it called the Wilmot Proviso, banning slavery from any territory acquired from Mexico but it was never passed.

it was no use..."1

Dejected with politics he returned to his law practice, which his junior partner William Herndon had been managing in his absence. Younger to Lincoln by ten years, he held him in great respect. They worked well together as a team and remained law partners till Lincoln's death in 1865. He devoted himself to his practice; they moved their office into a larger space; his reputation as a first class lawyer of high integrity grew. He began to appear before the Supreme Court regularly and continued to ride the Eighth Circuit. Though personally Lincoln was opposed to slavery, as a professional lawyer he had been representing both slaves and slave owners in courts. His cases became more diverse, — he had clients from capital cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia; he represented railroad companies, banks, insurance companies, merchants and manufacturers.

He always advised clients to settle matters amicably and to go to court only as a last resort. He took on cases that deserved merit and justice. Few lawyers in those days had the courage to take on fugitive cases, especially those with political ambitions, but Lincoln fearlessly accepted a case on its merit, irrespective of how it would affect his political career. An old widow who had been swindled by a pension agent; a free negro, who had foolishly gone ashore in a slave state and taken captive, his friend Armstrong's son, who had been convicted for murder, — all were accepted by him as clients and helped. The last one was saved by Lincoln's use of the farmer's almanac2 to prove that the moon was at a low angle on the night of the murder and the witness' claim that he had seen the accused in strong moonlight committing the crime was false.

Rarely did Lincoln raise objections in the courtroom, but if it ran against his principles of justice he did. And in the case of his cousin who was charged with murder, the judge, though a

- The Hidden Lincoln, Emanuel Hertz, p. 172

- Calendar

Democrat, sustained the objection, admitted the evidence presented by Lincoln and changed the verdict to 'not guilty'.

Likewise, honesty and integrity were priority for him, over and above the interest of his clients. He once represented a client against a railroad company, claiming an amount that they owed him. The jury voted in favour of his client and when they were about to announce the amount after deductions, he declared that the deductions needed to be more. Even though his statement would grant less money to his client, he would not let it affect his decision based on fair play!

Though he was an extremely successful jury lawyer, his earnings were moderate; around fifteen hundred dollars a year. He did not care to charge too much from his clients. His law practice was going on well, and life was settling down into a fine rhythm when in 1850, Lincoln and Mary suffered a terrible loss. Though they had looked after him day and night, Eddy, their four-year-old son died. They were both devastated. To fight off depression, Lincoln returned to the Eighth Judicial Circuit and poured himself into his work. He became a close friend of Judge David Davis, who had practiced law with Lincoln before he became a judge. He had to look after Mary too, whose behavior had become unpredictable; she would erupt at the slightest instigation, and at times he would simply leave the house until her temper cooled off.

Ten months later, in December 1850, their third child, William was born. His birth helped alleviate their loss considerably. But within a few weeks he got news of his father's death. Though he was her stepson, he cared for his stepmother's welfare much more than her own son did. Lincoln's concern about his stepmother's future is evident in his letter to his stepbrother, chiding him for selling their father's land and not making provisions for their mother's future.

Mary joined the First Presbyterian Church a couple of years later and though Lincoln attended church sometimes he did not become a member. In 1854, they were blessed with a fourth son, Thomas, whom he lovingly called Tad.

This sabbatical from politics gave him time to be with his boys; he was a loving, gentle father with tremendous patience and tolerance to overlook their peevishness and wild activities. Their sweetness and innocence were a constant source of joy to him. But for his time in court, he spent most of the time in their company. He would be seen giving them pram rides in the streets, and as they grew older he carried them around on his shoulders and read to them too. He was not strict with them nor did he impose rules on them. Though such freedom did result in unruly behavior in his children, he preferred to shower them with fatherly love rather than parental control. Willie was a lot like him, — very intelligent, with a mind far ahead of his age, methodical and capable of great activity. He was a beautiful boy who was also very loving, honest and had great retentive powers. Lincoln had passed on to him his sense of humour as well as his fondness for writing poetry. 'I know every step of the process by which that boy arrived at his satisfactory solution of the question before him, as it by just such slow methods I attain results'1 he would think of the special affinity he had with Willie.

Both he and Mary indulged the children tremendously, both at home and at the law office where they had a free run over tables and chairs, upsetting papers and ink stands, much to the chagrin of Mr. Herndon, his junior partner.

He also got time to study during this period; he decided to compensate his inadequacy in education by turning his attention to Mathematics and 'nearly mastered the six-books of Euclid'2. He often thought about difficulties he had experienced in navigating his boat down the rivers during his New Salem days. He was good at mechanics; he had built a flatboat when he was not even twenty. He pondered over the invention of a device that could be attached to the hull of a boat and inflated to lift the vessel safely over an obstruction in the river and finally acquired a patent for it (the only president who patented an invention), though it was

- The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, Michael Burlingame, p. 66

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Autobiography Written for Campaign, p. 162

never used commercially.

The gulf between the north and south had been widening on many fronts, — economically, politically as well as culturally — the north was evolving as an industrial people; most inventions and technical improvements came from the north, most industries were set up there, large cities developed, population increased with immigrants from Europe who settled there and found work in the factories and in building of infrastructure projects like railroads, bridges, roads. They preferred a strong central government since it helped their economy in many ways — it would ensure good infrastructure like roads and railways that connected states for the transportation of goods, and a common currency that was best handled by a strong central government; matters of taxation would also be best if it became a central issue. On the slavery issue, the north was divided into two factions, — the abolitionists who wanted to put an end to slavery immediately and the others who recognized that it would be logical to arrest the growth of slavery, and allow it to die out on its own.

The south, on the other hand, was predominantly agrarian, mostly growing crops such as cotton, which was heavily dependent on slave labour. They preferred to be sovereign states that could govern themselves; their taxation policy was often in conflict with those of the north and they felt that the central government favoured the north. Also, the Southerners felt that a strong central government would threaten the slave system that was fundamental to their financial prosperity. The policy of the central government to encourage people to go west was also a bone of contention for both the south and the north; the Northerners wanted every new state added to the union to be a free state while the Southerners wanted it to be a slave state. It was important for both sides since the population of each state determined the number of congressman it could send to the House of Representatives. The greater the representation of slave states, the greater the influence over the legislation of bills that favoured slavery.

Very soon after the commencement of the Mexican War in 1846, conflict between the southern slave states and the northern free states had begun on the question of admitting the territories as free or slave states. There were at that time 15 free states and 15 slave states. The Southern states led by John Calhoun, objected to admission of California as a free state since it would swing the balance in favour of free states politically; by 1850, nine of them even threatened to leave the Union. Whig leader Henry Clay and Daniel Webster suggested a compromise designed to appease both the south and the north.

Known as the Compromise of 1850 (see Map p. XII A), it admitted California as a free state, New Mexico and Utah were declared as territories where the issue of slavery was to be settled later, slave trade was abolished in Washington D.C. and a Fugitive Slave Law (much abhorred by and protested against by Northerners) was approved that facilitated slave owners to recapture runaway slaves with federal assistance. This compromise deferred the conflict between the north and the south.

In 1852, on the death of his former idol Henry Clay, Lincoln delivered a eulogy at Springfield. His adulation of Clay had waned and this shift in his perceptions was apparent in his words:

"But Henry Clay is dead. His long and eventful life is closed. Our country is prosperous and powerful; but could it have been quite all it has been, and is, and is to be, without Henry Clay? Such a man the times have demanded, and such, in the providence of God was given us. But he is gone. Let us strive to deserve, as far as mortals may, the continued care of Divine Providence, trusting that, in future national emergencies, He will not fail to provide us the instruments of safety and security."1

His prayer to the Divine for an instrument of safety and

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Eulogy on Henry Clay at Springfield, Ill, July 6th 1852, pp. 271-72

security seemed to be a silent offering of his own person for this task, as it were, — an offering that would manifest in his Presidential election eight years hence. The same year he canvassed for Winfield Scott, Whig candidate for Presidential elections after accepting the Presidential electoral ticket in 1852. Since victory for the Whigs in Illinois seemed impossible he did not invest too much of his time or energy into it.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet