Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body - The Roots Of The Martial Arts

Myth to History:

The Roots of the Martial Arts

Once primitive martial arts had reached the Far East they took root and began the gradual process of diversification into a number of sophisticated branches. Unfortunately there is very little evidence beyond myth, hearsay and speculation that relates to the early growth and spread of the martial arts. Yet fragments of information, drawn from the ancient literary and artistic traditions of China and India, suggest that the martial arts began to develop in these civilizations some time between the fifth century BC, when the mass manufacture of swords began in China, and the third century AD when the exercises on which the martial arts are based were first written down.

If this assertion seems impossibly vague compare it with efforts to pinpoint key events in the history of other ancient arts — cooking, wine-making, cheese-making or farming. The origins of such skills can rarely be traced with any accuracy, but from time to time a document or object is found which proves that by a certain date techniques had changed.

There are very few such documents or objects in the early history of the martial arts. Rather, many martial artists believe that their art began in China early in the sixth century AD.

Their belief is based on a legend that relates how there came one day to the Songshan Shaolin Temple and monastery at the foot of the Songshan Mountains in the Kingdom of Wei in China, a monk from India called Bodhidharma. He taught a new, more direct approach to Buddhism that involved long periods of static meditation. He is said to have sat facing a cave wall for nine years, arid to have instructed the other monks in the same way.

To help them withstand long hours of meditation he taught them breathing techniques and exercises to develop both their strength and their ability to defend themselves in the remote mountainous areas where they lived.

It is believed that from his teachings was born the dhyana or meditative school of Buddhism, called Ch'an by the Chinese and Zen by the Japanese. The fighting art known as Shaolin ch'uan-fa or Shaolin Temple boxing is held to be based on his exercises. Many Chinese and Japanese fighting arts are thought to have evolved from this tradition.

There is a great deal of doubt about the accuracy of this legend, but some of the historical facts it appears to reveal, if true, are of interest. The legend reflects the fact that mutual interest in Buddhism kept China and India in contact around the sixth century AD, a fact that is confirmed in the work of the great twentieth-century sinologist, Dr Joseph Needham. Furthermore, it implies that from very early times, meditation and martial exercises were complementary aspects of Buddhism; the one passive and static, the other active and moving.

Yet a careful search of the historical sources shows that the martial arts were already blossoming in both India and China long before the journey of Bodhidharma.

The fighting traditions of the Far East

What was military life like in China and India between 500 BC and the third century AD? Were the conditions right for the evolution of the very specialized form of fighting which could later be identified as the precursor of today's martial arts?

The evidence has been neither researched nor presented with this specific academic question in mind, but the ancient military systems of China and India are quite well recorded and enough information exists to give a picture of military life in those times and places. Since war fare and the martial arts are both essentially about fighting, it is useful to take a brief look at the development of the fighting traditions of the ancient East.

Before 500 BC China did not exist as a nation. The territory occupied by the People's Republic of China today was divided into a large number of minor, independent states, whose social systems were essentially feudal in structure.

Warfare was endemic, but armies of peasants, led by local war lords, were often small. The war lords would be driven in chariots to the battlefield to fire arrows upon the poorly armed peasant infantry mustered by their opponents. On occasions they would even hold single combat (a style of warfare that was essentially a martial art), before

their opposing armies, to decide the issues at stake.

Wars were conducted in a highly ritualistic fashion. They were prohibited during certain seasons and in some other circumstances, such as after the death of a leader. Armies might lounge for days while omens and oracles were consulted to determine the timing of a strike.

Gradually the smaller states were swallowed up by larger ones, and, as prosperity increased, cities of as many as 750,000 people grew up in China. By the end of the fifth century BC trade between these population centres had expanded greatly. Among the items traded by merchants would have been the tools and weapons of high quality that ironmasters were beginning to manufacture on a large scale. A low grade kind of steel was perfected, so the first rulers of the Warring States Period (480-221 BC) were able to equip their armies with weapons manufactured in foundries and stored in arsenals.

An expansion of the ancient state bureaucratic machine provided for equipping and feeding these armies, and also for training them. The art of war, earlier confined to the aristocratic war lords, became the province of professionally trained and equipped officers and men.

As a result, warfare became much more destructive, devious and decisive. Armies of several hundred thousand men, including their sup port forces, took to the field.

With professional armies came a new generation of specialists: experts in engineering, cartography, signals, amphibious operations and so on. The most famous of these was Sun Tzu, a brilliant tactician and strategist whose book, the Art of War (c.350 BC), is still essential reading for all ambitious military personnel. Sun Tzu's thoughts on warfare are said to have influenced Mao Tse-tung.

By 300 BC, therefore, the military arts had passed the stage of martial arts as practised by local war lords. Nevertheless, conditions in other, non-military, aspects of Chinese life may have encouraged the development of the martial arts.

Through the Warring States Period and thereafter, the Chinese countryside was rife with groups of bandits and outlaws. However, there were great profits to be made from interstate trade. Merchants must have employed bodyguards to protect themselves and their goods from brigands.

Employment as a bodyguard, in which small-scale, close-quarter com bat was to be expected, suited the martial artist perfectly. Accompanying

trade caravans to distant parts of the land would have exposed the bodyguards to the hardening rigours of long journeys under harsh travelling conditions, and to the knowledge and techniques of other body guards. It may have been under these circumstances, then, that the martial arts evolved in the East.

Yet the emergence of a martial art depends on more than the practice of skills and the endurance of hardships. The martial arts have an intellectual content. They embody sets of values and are based on specific views of the world and of man's place within it.

China's two great philosophers had lived during the first half of the second millennium BC. Confucius had laid down theories of man and the way of human society around 500 BC. Lao Tzu is thought to have expounded his mystical vision of man and the tao or 'way of nature' around 300 BC. Taoism is particularly important to the history of the Chinese martial arts, although it is only recently that Taoist martial arts have spread beyond the bounds of Chinese Asia.

Similarly, the philosophy of Buddhism, founded by the Prince Gautama Siddhartha Buddha who was born in north-eastern India around 560 BC, has profoundly affected the martial systems of all countries where the two have met, be it in China, Japan, India or South East Asia.

It was therefore during the latter half of the first millennium BC that the philosophies upon which the martial arts depend were first laid down. Although some arts may have evolved at a much later date, the conditions for their development were established when these creeds were first promulgated.

India has always been a breeding-ground of warriors. The India into which the Buddha was born was composed of a large number of small kingdoms. In some areas tensions led to continual feuding and raiding between kingdoms. Yet occasionally, for example under the great Emperor Ashoka (268-231 BC), large areas of India were united under one leader. Ashoka, Emperor of the Maurya Dynasty, whose empire covered some two-thirds of the Indian sub-continent, began his rule as a warrior king, but after his conversion to Buddhism, he renounced warfare as an act of policy.

Throughout the second half of the first millennium BC, southern India especially was ruled by successive dynasties of kings of different religious convictions. Yet the wars these kings waged were generally

on a smaller scale, more ritualized and less destructive than those happening in China at that time.

Neither does the same degree of military specialization appear to have taken place in India, as in China. It is likely that in India the martial skills were part of the overall training of an accomplished man, especially one born into an aristocratic warrior class. The classic Indian tradition relating to the accomplishments of an individual are usually attributed to Agastiya, the mythical founder of Indian art and sciences. Among the arts he advocated were martial skills of armed and unarmed combat.

Buddhism never succeeded in ousting the traditional Hinduism as the first religion of India, although it survived there for more than 1,500 years. Yet, when the teachings of Buddhism reached China, they immediately attracted the attention of courtiers, scholars and aristocrats.

Records from history

The military styles of China and India were entirely different and yet there is a close relationship between the martial arts of the two countries. Not only are there similar patterns of movement in, for example, kalaripayit practised by a peasant in South India and kung fu practised by a waiter in Hong Kong, but even the secret techniques are used in similar ways.

Anyone who accepts the Bodhidharma legend as true has no difficulty in understanding this, but early written sources throw no light upon the origins of these similarities.

There has recently been much searching among ancient Chinese texts for proof that the martial arts existed in China before the coming of Bodhidharma in the sixth century AD. The most publicized find so far has been a set of exercises recorded by a famous doctor, Hua Tuo. He based them upon the movements of five animals: the tiger, the bear, the monkey, the stork and the deer. This relationship between animals and movement is fundamental to Chinese martial arts as practised today, but what is most significant is that Hua Tuo lived at the time of the Three Kingdoms (AD 220-65), well before Bodhidharma arrived in China.

In a newly published book, Shaolin Kung Fu by two Chinese scholars, Ying Zi and Weng Yi, the authors claim that a fresco in a tomb dating from the Han Dynasty, about AD 200, shows two men in a martial

arts stance. The fresco, called Sumo (although it bears no apparent resemblance to the Japanese form of wrestling or grappling called sumo), if authentic, is the oldest painting known to represent the martial arts, but from the photograph it seems to have been repainted.

At around the time that this picture is said to have been painted, ancient teachings were being written down in the Tamil language of South India. These writings included sastras, ancient Indian texts, which described in detail methods of striking the vital points (the spots on the body where a precise blow can knock out or kill) of an opponent, as well as the use of weapons in combat. The Indians claim that these texts are part of a much older oral heritage, but there is no corroborating evidence to support them.

Cultural exchange

The known written sources do not resolve the controversy about the comparative antiquity of the martial arts of India and China. Yet, if there is a mutual relationship between the arts of the two countries, there must in the past have been an interchange between people who needed the kinds of skills the martial arts could offer. For hundreds of years two kinds of people were the principal travellers between India and China. They were monk-scholar-diplomats and merchants. The routes were forged by trade, and merchants making those vast journeys must have needed the protection of bodyguards, just as they had always needed them on their trading journeys over the vast distances of China.

Employment as a bodyguard would have given a training in the kind of man-to-man fighting on which the martial arts were based. Moreover, travelling with trade caravans would have exposed the bodyguards to the influence of the different fighting styles practised by the various races encountered along the way. In this manner, martial knowledge would have been disseminated beyond the borders of India.

The journey from India to China was always gruelling. One route passed through Afghanistan, then north or south of the great Takla Makan desert that lies to the north of Tibet and east of China. By the end of the second century BC the larger part of this route ran along the Old Silk Roads down which Chinese silk passed to the frontiers of the Roman Empire in Syria.

It takes great determination to travel along these roads. Peter Fleming, the great English travel writer of the 1930s, brother of Ian Fleming,

struggled against weather, bureaucracy and war lords on his journey along the Old Silk Roads, much as the travellers did when forging links with the West some 2,000 years earlier.

Merchants began using this road before the birth of Buddha in the mid-sixth century BC, but as Buddhism gathered strength they were joined by monks from India. Consequently, by AD 65 the first Buddhist community had been established in China.

That event marks the beginning of an invasion of Chinese custom and thought by the culture and philosophy of the Indians. Buddhism gradually became a powerful force within China and as it did so, violent power struggles broke out between Taoists and adherents to the invading religion.

Meanwhile, Indian monks travelling to China to disseminate the Buddha's teachings passed on the road Chinese monks on their way to India. They were pilgrims visiting the holy places where the Buddha had passed parts of his life, and were searching for the sutras and sastras of the Buddha's teaching that had been written down in the traditional manner on palm leaves.

Most famous of these scholar pilgrims was Hsuan-tsang (c.AD 600 64) who travelled the length and breadth of India between 629 and 645. In India he was called Tripitaka, and in that guise he was later immortalized as the pilgrim priest of Monkey, a collection of legends written down by the sixteenth-century Chinese writer, Wu Ch'eng-en.

Tripitaka travelled to India to find the sacred texts, accompanied by Monkey and three other guardian spirits, all of them expert martial artists. The legends, which arose after the seventh century when Hsuan-tsang lived, are full of descriptions of the epic battles they fought with the demons and monsters living along the way.

On his travels to southern India, Hsuan-tsang visited Kanchipuram, a possible birth place of Bodhidharma, where he became a friend of the king, and where his face can still be seen carved on the wall of a temple built shortly after his visit.

The perils of travel were real. He was captured by bandits and escaped, because, as he prayed for help, he went into a trance and a sudden wind blew up, frightening the bandits.

Another monk, I-Tsing, described his own escape in his book The Buddhist Religion as Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago, written between 671 and 695:

'At a distance of ten days' journey... We passed a great mountain and bogs; the pass is dangerous and difficult to cross.... At that time I, I-Tsing, was attacked by an illness of the season; my body was fatigued and without strength. I sought to follow the company of merchants, but tarrying and suffering, as I was, became unable to reach them. Although I exerted myself and wanted to proceed, yet I was obliged to stop a hundred times in going five Chinese miles... I alone remained behind, and walked in the dangerous defiles without a companion. Late in the day, when the sun was about to set, some mountain brigands made their appearance; drawing a bow and shouting aloud, they came and glared at me, and one after another insulted me. First they stripped me of my upper robe, and then took off my under garment. All the straps and girdles that were with me they snatched away also... There was a rumour in the country of the West (India) that when they took a white man, they killed him to offer a sacrifice to heaven.... Thereupon I entered into a muddy hole, and besmeared all my body with mud. I covered myself with leaves, and supporting myself on a stick, I advanced slowly.' He reached his friends late that night.

It is clear from such descriptions that not all monks were trained fighters, but doubtless, such experiences must have made travelling monks keenly aware of the need to learn the arts of self-defence.

To recapitulate: first, there is no clear evidence that points to China or India as the country where the martial arts first developed into the systems of action and thought that approximate to the Asian martial arts of today.

However, records of many aspects of these ancient cultures have a bearing upon the origins of today's martial arts.

In a purely physical sense, the fighting systems of ancient India, in which a warrior class was expected to be conversant with a wide range of skills, seems to be more compatible with the development of martial arts than the more specialized approach of the military men of China.

At the level of ideology, however, the doctrines of Buddhism in India and of Confucianism and Taoism in China, laid down during the 500 years before the birth of Christ, have been readily adopted as the philosophical basis of martial traditions in India and China, and indeed throughout Asia.

Recorded sources relating directly to the history of the martial arts are too fragmentary to be conclusive. Yet the long history of cultural

interchange between China and India means that it is highly likely that martial knowledge was shared between these two cultures from the earliest times.

Therefore perhaps it is better not to try to choose between the two countries, but rather to remember the travellers, the monk-pilgrim diplomats and the merchants, who beat the first paths between the two great cultural traditions, and to conclude that the birth place of the martial arts was on the roads that bound these two great civilizations.

The spread of the martial arts

The story of the martial arts from the third century AD has been one of the gradual development of their techniques, the enrichment of their philosophies, and of their slow spread into other countries, usually as a travelling companion of Buddhism.

Many different martial arts have evolved in India and China during the last 1,500 years, and many are still practised, but most of them have emanated from the founding schools; most kung fu, for example, is believed to have evolved from Shaolin Temple boxing. The complete martial arts systems, consisting of ideology plus practice or technique, were exported beyond the borders of China and India to Korea, Japan and South East Asia.

These countries must have had their own fighting arts, but as the superior techniques and advanced ideas from abroad were absorbed by their fighters, they were changed, and the changes resulted in a trans formation of the indigenous systems into true martial arts.

The existing martial arts systems of Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Indochina and Korea are all clearly related to forms of Chinese boxing. However, it is the intellectual content that distinguishes a martial art from a fighting art. Although the dissemination of the martial arts from country to country can be traced, it is not yet clear when the process of assimilation took place and the indigenous arts became martial arts.

The Japanese, who were strongly influenced by Chinese culture, learned the lessons of the ancient masters most thoroughly early in their history. On the basis of Chinese techniques, the Japanese slowly evolved their own martial arts forms. Now, Japan is the richest country in Asia, both in the variety of martial arts and in the numbers practising as a proportion of the population.

The Western view of the East

In the West, however, knowledge of the martial arts of the East hardly existed before the twentieth century.

It was not until the beginning of the fourteenth century that Europeans set out on the first voyages of discovery. From 1400 onward, successive explorations gradually revealed to them a world whose non European inhabitants astonished them.

Yet the peoples of East Asia remained unaffected by discovery. They showed little interest in the newcomers from Europe, whom they considered barbarians, and were content to remain unexplored.

Having lost traces of their own past, European explorers had to re establish the links forged centuries before by their ancestors. They had forgotten the contact established with India by the Greek King, Alexander the Great, during the fourth century BC; the settlements established in southern India by the Romans during the first century AD, and then by early Christians; and the opening of the Silk Roads, which stretched from the Mediterranean borders of the Roman Empire to Central China as early as the beginning of the first century BC, more than 14 centuries before Marco Polo travelled along them on his journeys of discovery.

Moreover, Renaissance Europe was not the world centre of intellectual life. Four of the world's great religions were created in the Far East. Both India and China had advanced medical systems, and had made great progress in the fields of mathematics, chemistry and astronomy.

In the field of technology, the British sinologist, Dr Joseph Needham, in his erudite series of volumes, Science and Civilization in China, lists 34 Chinese technological innovations that were used in China long before they were discovered elsewhere, and that reached Europe and other parts of the world between the first and the eighteenth centuries AD. Among them were the wheelbarrow, silk textile-producing machinery, the cross-bow, gunpowder, the magnetic compass, paper and printing. On the other hand, only four inventions produced in the West were transmitted to China during the same period. They were the screw, the crankshaft, clockwork and the force pump for liquids.

Knowledge of the Asian martial arts hardly existed before the twentieth century. Around 1900 two or three Englishmen and as many Americans began to learn judo and other Japanese martial arts. Interest grew only slowly, however, until after 1945 when, as a result of the

enthusiasm engendered by American servicemen who had studied the martial arts while stationed in Japan, the numbers practising increased dramatically.

These learned mainly Japanese techniques, however. The spread to the West of knowledge about the martial arts of other parts of Asia has been even slower. Chinese masters practising in Hong-Kong and Taiwan have begun to respond only recently to pressure from Westerners to reveal their techniques so that their arts can be taught in Europe and the USA.

At least one eastern art has yet to be reported in the West. Even experts have largely neglected the existence of martial arts in the Indian sub-continent. No descriptions of Indian martial arts made during the period of British rule have so far come to light. Yet in India the ancient fighting art of kalaripayit, which has existed in the south for centuries, has not yet been described,

Martial arts systems are exported wholesale to the West. There, people are still learning and it will be some time, perhaps generations, before martial arts systems emerge that can be called European or American in the same way that, say, judo, can be called Japanese.

The Enigma of Bodhidharma

There is some evidence that in the year AD 520 an Indian monk, thought to have been born in Kanchipuram near Madras, travelled to the city of Kuang (modern Canton) where he was granted audience by Wu Ti, an Emperor of the Liang Dynasty. From there he travelled to a monastery in the Kingdom of Wei, where he spent long hours in meditation.

If the legend of Bodhidharma is true and he did visit the Songshan Shaolin Monastery, he is doubly important in the history of the martial arts, for not only did he establish Shaolin boxing, but he is also the first patriarch of Ch'an or Zen Buddhism. As such he is the patron saint of most Japanese martial artists, who call him Dharuma and hang his Bodhidharma

portrait in a position of honour in their dojos or training halls. In these portraits, Bodhidharma is always ugly. He has glaring blue eyes, wild, dark, curling hair and a beard.

The founder of Shaolin boxing and Ch'an or Zen Buddhism is a mysterious person. Biographies were written of many of his contemporary monks, but he, most important of all to the followers of his teachings, is ignored. There exists only one eyewitness account of him in a piece of writing by Yang Hsuan-chih, a Chinese citizen of Lo-yang, in modern Honan, which was completed in AD 547 and is entitled Lo yang chia-lan-chi (Record of the Monasteries in Lo-yang).

The author describes an occasion on which he climbed up to the great Yung Ning Temple with the Prefect of the city of Lo-yang, and there met Bodhidharma: "... at that time also there was the Sramana of the Western lands, Bodhidharma, who was basically a Hon of the Kingdom of Posseur (Persia). Before the marvels of the temple he said he was 150 years old, that he has traversed in all directions many and different kingdoms and there was not the equal of this temple for beauty."

It is possible to date this meeting. The temple was built in 516. It burned down in 535, but from 528 troops were billeted in it, so the meeting must have taken place between 516 and 528.

It is very useful to have an account that seems to prove that Bodhidharma did exist, but it must be considered with caution. Chinese texts were copied many times and there were frequent mistakes in copying. Moreover, mistakes occur in their translation into other languages. This is an English version of a translation from Chinese into French by a famous orientalist, Paul Pelliot, and is therefore doubly subject to error.

Supposing the translation to be accurate, what is its meaning? What language did Bodhidharma use when talking to the author? Was he fluent in Chinese? Did he mean to say he was 150 years old? If he did, was he saying what he thought was true or speaking in riddles in the manner of later Ch'an and Zen monks?

Does the phrase 'basically a Hon of Posseur' mean that he looked like one or was one? Pelliot thinks that it means the 'Hon with the blue green eyes'. The person he was describing could have been an Indian, even if his colouring was fair. In the north-west of India there were many fair-skinned, blue-eyed people.

After this report, which is frustrating because it is incomplete, there

is hardly a mention of Bodhidharma in any text for almost 500 years. Even Hsuan-tsang, the seventh-century Chinese scholar-pilgrim, who visited both the Shaolin Temple and Kanchipuram 100 years later, fails to mention him. Then, suddenly, around the eleventh century, books appear containing long, complex narratives describing his days in China and his teachings in the martial arts.

This gap of four centuries seems inexplicable. However, there is an argument that fits the facts and provides an explanation.

When the teachings of Ch'an or Zen Buddhism first appeared they were radical, and possibly also heretical. Chinese scholars of the time lived for the study of manuscripts and their religious practices were full of elaborate rituals conducted in temples.

In the Ch'an sect, however, religious practices were simple, there were no manuscripts and even the Buddha was not needed. Ch'an Buddhist teachings say: 'you will find the Buddha if you look directly into your inner essence'. Ch'an Buddhism, a religion in which postulants seek sudden inner enlightenment, is without objects of veneration.

A telling quotation from about 840 sustains this view. A Ch'an master, Hsuan-Chien, is recorded as having said 'There are no Buddhas, no Patriarches. Bodhidharma was merely a bearded old barbarian... the sacred teachings... sheets of paper to wipe the pus from your boils'. Bodhidharma, reckoned among the most important of saints was yet, according to Ch'an beliefs, unnecessary.

Ch'an was eventually to surface at the time of the persecution of other Buddhist sects that took place in China in AD 845. This movement was directed against the wealth and power of monasteries, but since Ch'an did not rely for its existence upon the accumulation of wealth and material objects the Ch'an sect escaped persecution.

Yet as their sect, no longer considered heretical, survived, became established and prospered, the monks, like all religious, would no doubt have felt a need to record the life and to spread the word of their great founder.

The books in which Bodhidharma's teachings were expounded were all written long after his death; and the books of exercises probably not for 1,000 years. However, any shred they may contain of his martial arts teaching must have been changed and diluted through the centuries of oral tradition, so as to be scarcely recognizable today.

Since all the records of the Shaolin Temple were burned in 1928, it is

unlikely that more documents will be found to prove that Bodhidharma deserves his position as the patriarch of Ch'an or Zen and the martial arts. His teachings, nevertheless, live on through the practitioners of the arts he is said to have founded.

It was the master of the Chinese internal arts, Master Hung I-hsiang, who finally made clear to us the significance of Bodhidharma's teachings. He explained that it was Bodhidharma who introduced into China the notion of wu-te or martial virtue. By this he meant the qualities of discipline, restraint, humility and respect for human life. As he put it: "Prior to the arrival of Ta-Mo, Chinese martial artists trained primarily to fight and were fond of bullying weaker folk. Ta-Mo brought wu-te, which taught that the martial arts are really meant to promote spiritual development and health, not fighting."

The Village Art of Kalaripayit

About an hour before dawn the children of a little South Indian village gather in a nearby quarry. It is lit by fading moonlight and a suspended fluorescent tube. They talk together, their voices quiet against the sudden harsh sounds of an awakening village: a bucket being filled in a well; a long, agonizing burst of coughing. Then the Master arrives and, after proper salutations to the gods and to him, they start their morning session of kalaripayit, the martial art of South India.

They practise for about an hour, twisting and turning with extraordinary agility, the sounds of their breathing always counterpointed by the sounds around them — the calls of the first flight of crows across the brightening sky; the almost silent footsteps of an elephant padding softly on his way to a building site; the earth being swept clean by the mothers of the practising children; and the local temple switching on its tape to send electronically distorted holy music echoing over the fields. Finally, as the sun touches the tips of the coconut palms, the children finish their class and go to school or to work.

As there are no masters nor schools of kalaripayit known to be operating outside India, it is possible to understand why it has been so neglected by students of the martial arts. It is extraordinary, however, that none of the researchers and writers who have been studying the martial arts for many years should have reported the existence of kalaripayit. Those few writers who have mentioned it merely make reference to an imported system similar to karate. Yet it is difficult to believe that any

one who has watched Indians practising kalaripayit could so describe it. However, because this attitude exists, we feel we must make a case for this almost unknown martial art.

There are two points that need to be established. First, is it an indigenous martial art, or is it imported? Second, has it continued unchanged since earliest times, or did it die out and then revive, per haps in some other form?

It can be proved that the martial arts were practised in South India during the sixth and seventh centuries. Statues in the Temple at Kanchipuram near Madras, built early in the seventh century AD show the use of complex disarming techniques as well as many weapons in use. There are also the eye-witness accounts of Hsuan-tsang, the famous Chinese pilgrim-scholar-diplomat, who wrote of the Indian weapons that he saw on his journey.:

'The chief soldiers of the country are selected from the bravest of the people, and as the sons follow the profession of their fathers, they soon acquire a knowledge of the art of war. These dwell in garrison around the palace (during peace), but when on an expedition they march in front as an advanced guard. There are four divisions of the army, viz.(1) the infantry, (2) the cavalry, (3) the chariots, (4) the elephants. The elephants are covered with strong armour, and their tusks are provided with sharp spurs. A leader in a car gives the command, whilst two attendants on the right and left drive his chariot, which is drawn by four horses abreast. The general of the soldiers remains in his chariot; he is surrounded by a file of guards, who keep close to his chariot wheels.

The cavalry spread themselves in front to resist an attack, and in case of defeat they carry orders hither and thither. The infantry by their quick movements contribute to the defence. These men are chosen for their courage and strength. They carry a long spear and a great shield; sometimes they hold a sword or sabre, and advance to the front with impetuosity. All their weapons of war are sharp and pointed: spears, shields, bows, arrows, swords, sabres, battle-axes, lances, halberds, long javelins, and various kinds of slings. All these they have used for ages.'

Many of the weapons described in this extract from Records of Western Countries Book II by Hsuan-tsang (c.600-64) are still in use today.

There are much earlier Indian texts, which were written down on palm leaves, and, since wood-eating insects and fungi attacked them, they were copied time and time again over the centuries. Indian scholars make a special study of dating such texts, which are on literary, medical and religious subjects, as well as the martial arts. The South Indian texts on the martial arts were written in early versions of Tamil, a language that was first written down after AD 200.

The copying of such texts is still common in South India. They are written with a sharp point on the palm leaves and then rubbed with lampblack which adheres in the cracks made with the point. The present day masters of kalaripayit usually have versions copied from those of their masters.

Another line of evidence for kalaripayit as an indigenous art comes from traditional Indian folk and classic dancing. These have clear relationships with kalaripayit. In ancient Indian classic dance, for in stance, many postures are strikingly similar to those of kalaripayit, and in kathakali dance theatre, one of the four classic Hindu dance-dramas, established during the 17th century in Kerala State in South India, many poses are very similar indeed to the postures of the martial arts.

There are other strong points which support this evidence. From prehistoric times India has had an entire class whose function was to wage war. The kshatriyas, traditionally the military and ruling class, supported their king in his quarrels with his neighbours. As members of a warrior class they had the time to practise, and they were exactly the kind of men who would be ingenious in their thinking about fighting. A warrior class would also keep a fighting tradition alive for as long as it lasted.

However, perhaps the strongest evidence, both for the argument that kalaripayit is an indigenous Indian art, and that it has continued since earliest times, comes from the way in which the art is practised in modern times. If it were an imported art, it would be based in cities and practised by the educated, sophisticated Indians. This is exactly what is happening with karate today.

Kalaripayit is, on the contrary, practised mainly by villagers, who are so notoriously conservative that the idea that they may have been taught a foreign fighting system seems ludicrous. Kalaripayit is deeply embedded in the social and religious life of the peasants over a huge area of South India, and so it must have been for thousands of years.

The masters of kalaripayit

The lives of the masters in their different villages generally follow the same pattern. After the morning's practice with the children, they turn to their other important function, that of doctors to the neighbourhood.

It is customary in the martial arts that the masters are also doctors. Because of the nature of the art, a person who practises fighting techniques for a long time becomes increasingly absorbed in medical knowledge, since almost every day someone will be hurt in practice. As a young student the master learns how to heal minor bruises and strains, but as he becomes a serious student with the possibility of eventually becoming a master, he will study more widely, learning how to set bones and heal internal injuries. Many masters remain at this level of knowledge, but others go on to study the full range of their indigenous medicine.

A day spent with such a master and doctor while he treats his patients shows how much western medicine is limited by its scientific block busting, pill-dispensing techniques. Even at the level of a village doctor the traditional (Ayurvedic) system of medicine in India shows a depth of care for the patient that is rare in the West.

Many of the patients are men who have hurt themselves while working, usually by working too hard. A day lost to a poor fisherman while he visits the doctor is a real loss, which continues until the doctor can help him to gain enough strength to go back to hauling the nets.

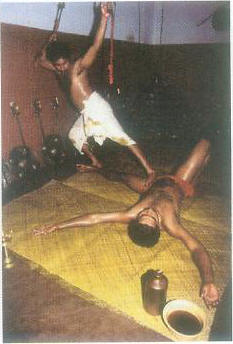

Deep, powerful massage is a most important part of the healing process. This mainly takes the form of foot massage. The doctor, sup porting his weight on a rope stretched across the room, works his feet over the patient's oiled body.

One of the masters we worked with, Master Mathavan, runs a small private hospital, an old, mud-walled building with deep, thatched eaves set among coconut palms. Inside it is cool, scented by herbs and massage oil carried on a gentle breeze. Babies sleep on the clean earth floor while their mothers are treated by the Master's wife. Outside there is a special herb garden where the medicinal plants grow. There is no profit in such caring; very few patients can pay the few rupees that represent the real cost of their treatment.

After surgery, in the evening when the young men come home from their day's work, it is time once again for kalaripayit.

The northern and southern styles

The name kalaripayit is taken from two words used by the Malayalam speaking people of Kerala. Kalari means battlefield or place, and payit means practice. So the term literally means 'battlefield training or practice'. Kalaripayit comprises two major styles which, being divided geographically, are consequently known as the northern and southern styles.

The northern style is practised mainly by the Nayars, a Malayalam speaking people who are part of the Aryan cultural tradition of North India. The southernmost part of India is occupied by Tamil-speaking people, descendents of the area's ancient inhabitants, who practise the southern style. This style is also taught in Madras, although probably only by Tamil immigrants.

Curiously, there seem to be no masters between Nagercoil on the southernmost tip of India, and Madras. Although no official census has yet been carried out there are probably more than 100 masters of each style. They teach throughout the year except during the hot, dry season, from January to April, when all teaching stops.

Although the northern and southern styles are obviously closely

related, and kalaripayit generally is quite different from the other martial arts, significant distinctions can be made between the two styles. At the geographical boundary between the two cultural groups and fighting styles there is some overlap. A few Malayalam speakers also practise the southern style in their area.

Northern Kalaripayit is practised in a building of fixed dimensions — 14x7 meters (42 x 21 feet) — with thick walls and a floor that is a meter (three feet) or so below ground level. This building, the village kalari or battleground, is the property of the master, who may also use it as a surgery and massage parlour. Students always practise indoors and at night, so as to maintain secrecy.

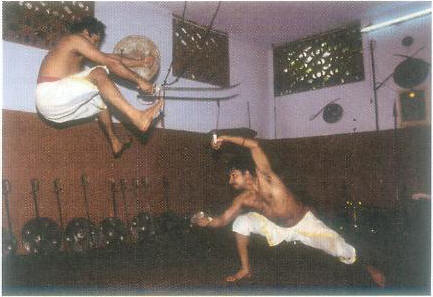

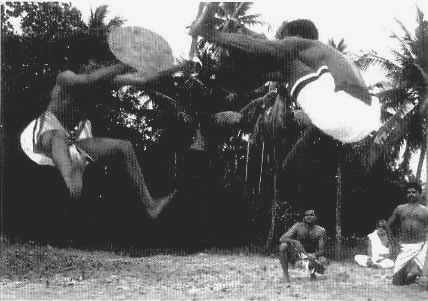

Technically, the northern style is characterized by very high jumping and kicking techniques, long strides, low stances, and blows and blocks delivered by arm and hands that are almost fully extended. Warming-up gymnastic techniques are very strenuous. Peculiar to the northern style is a whole range of armed and unarmed forms or patterns of movement called suvadus, and several breathing techniques, probably taken from yoga, that are found in its training regimen.

The southern style is often practised outside during daylight hours. Some masters use outdoor pits or hollows as training grounds, but others simply teach under the palm trees behind their houses. Many southern masters have training grounds in several villages and spend much of their time travelling between them, teaching at each one either at dusk or dawn.

There are fewer elaborate altars to the Hindu gods in southern training grounds, although students of both styles must perform salutations to both their martial gods and goddesses, and their masters, before training. A whole pantheon of gods is associated with the kalari, but the principal figure is Kali, goddess of war.

The southern style contains more circular movements and perhaps looks cruder than the northern. Strikes and blocks are usually delivered with the hands open and the arms bent. The southern ways of using weapons, and southern forms, the basic patterns of movement used in practice, are different from those of the northern style. There are few of the high jumps and kicks found in the north, but higher, more solid stances and a powerful use of the arms, shoulders and torso.

The Southerners are perhaps a little less energetic than the Northerners, but nonetheless impressive in their strength and toughness. They

constantly fall, roll and are thrown on to the dusty, stony ground, and always come bouncing back with dirt clinging to their clothes and limbs.

Where the Northerners generally concentrate on the perfection of form, the Southerners aim for effectiveness and strength in action. It is not so much the content of the art (which is substantially the same in both styles) as differences in language and culture, and the execution of the movements, which divide kalaripayit into two distinct styles.

In both styles the art of kalaripayit is composed of four branches of combat techniques. There is unarmed training; training with bamboo or rattan sticks; training with a range of weapons; and for the most advanced students there are the secret techniques of striking vital points, known in India as marma-adi. Besides these basic types of training, students also practise disarming techniques against weapons and sticks, and the use of several wrestling holds such as throws, locks and pin holds or techniques for pinning an opponent to the floor. Students learn all these branches of the art from the beginning, but, following the widely held theory that weapons are essentially an extension of the limbs, the emphasis is placed upon unarmed techniques.

Training

In the following pages we shall give a detailed description of the training regimens followed by the schools that we visited and filmed in the Kerala and Tamil Nadu states. Kalaripayit has not yet received the attention it deserves from the rest of the martial arts fraternity and we hope that this report will stimulate other serious researchers into carrying out more detailed and long-term investigations of this ancient and fascinating art.

Kalaripayit as we saw it is still largely a village art, practised in many of the rural communities of south-west India. People become masters only after long and arduous training periods, and most of the 40 or so masters we met were more than 50 years old. Almost all were also masters of the traditional Ayurvedic medicine.

Some masters were very secretive and taught only a few students, others had large, flourishing schools with 40 or more students attending training sessions. These are held during the cooler hours of the day, either before eight o'clock in the morning or around dusk; they last for about one and a half hours. Most masters like to teach their

students at least twice a week.

The youngest students we saw were youths of ten or so. There were also some beginners of 30 years old, many of whom had been told to begin training for medical reasons. A few girls and young women study the art. Those students who had clearly been studying intensively for several years were superbly fit and had excellent physiques and great agility, speed and endurance.

Before a student begins to train in kalaripayit, he or she must under go daily massage by the master. This loosens and stretches the muscles and tendons in preparation for the exertion of training.

The student is rubbed with coconut oil infused with herbs and lies down on a slightly curved wooden platform. Balancing himself by grasping a rope which hangs about one and a half meters (four and a half feet) above his head, the master uses his feet to massage the student's back and limbs, pushing outward from the centre of the body. He may stand on the student while doing this, but the pressure and pushing movement of his foot is minutely controlled.

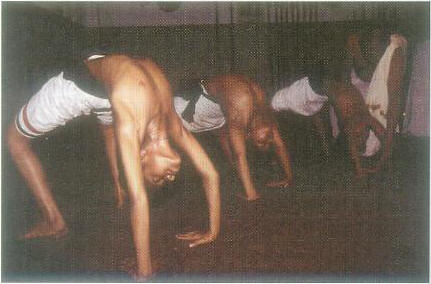

Before the master calls his class to order, just as in any martial arts academy in the world, students of all grades mill around practising forms, warming up or sparring lightly. There follows an elaborate pattern of salutations in which each student pays respect to mother earth, the master and the gods of the hall. The salute consists of a complex set of moves — making fighting gestures, walking in circles, touching the ground and kissing the master's feet. The class then forms two lines. Together, they work through a rigorous set of warming-up exercises to tense and stretch

muscles, tendons and joints. Some of these exercises, such as press ups and sit-ups, are found in most western fitness programmes, but several are peculiar to India.

In one exercise, similar to a press-up, the students put their right arms behind their backs and take up the press-up position. They lower themselves on their left hands to the ground, twisting their bodies at the same time. The degree of suppleness required to perform these exercises at speed is similar to that of an acrobat or contortionist.

The gymnastic part of a training programme is designed not only to warm up the muscles and flex the tendons and joints in preparation for martial training, it also plays a major part in developing fitness. Students may be told to execute 20 or 30 press-ups or similar exercises to improve their circulation and breathing, and also to strengthen the muscles.

After half an hour or so of gymnastics the students go on to practise empty-handed techniques, the basis of their art.

Empty-handed techniques

The strikes, blocks and kicks of which kalaripayit is composed are rehearsed one after another, sometimes by students standing alone and sometimes in pairs, with one student defending while the other attacks.

As the name implies, most of the strikes are delivered with the hand held open, flat and rigid. The hand in this position may be used like a knife, either to 'cut' with the side of the hand, or to 'stab' using the points of the fingers. The hard, body part of the palm near the wrist, and the clenched fist, are also used for striking. Blocks are mainly circular, that is, the arm makes a sweeping, circular movement to deflect the blow. The forearm is the point of contact.

Most kicks in the southern style are low, and are delivered to the front of the body, but the roundhouse side kick (in which the knee is lifted to the level of the waist, with the foot held out to the side, and the kick penetrates the opponent's side) is also used occasionally. The upper surface of the foot, the big toe and the ball of the foot are the contact points. In the northern style kicks are very high. Some students can raise their front kicks almost two and a half meters (seven and a half feet).

Great emphasis is placed upon evading, rather than blocking, kicks, and to this end many of the pre-set forms consist of leaping from very low stances, then landing in the upright posture. In combat footwork kalaripayit adepts of both styles characteristically lift their heels very high behind them, giving an impression of strutting that is unique to this art. The movement is designed to avoid stumbling on the rough South Indian terrain.

In a blocking technique which is unique to kalaripayit, one fighter raises a foot in a high forward kick to push the opponent's biceps back ward. This technique, which will halt an incoming blow, is very effective,

Grappling techniques

All the techniques we have described so far are typical of the kick-boxing tradition that may date back to the age when Babylon flourished. However, kalaripayit consists of many more techniques than these.

One complex of techniques centres on the use of grappling, locks, throws and methods of immobilizing an opponent. Pressure may be

applied against joints, limbs twisted or nerve points pressed in order to neutralize the attacker, or to throw him clear. Curved movements and bent limbs, and a relaxed physical and mental state, are needed to exe cute such techniques effectively.

Some of these practices clearly derive from the great Indian traditions of wrestling and grappling, whose roots extend even further than kalaripayit into the past. However, others are not related to this tradition. The complex locks and throws found in Kalaripayit in the soft Chinese arts, today are also found in ju-jutsu and aikido in Japan, in eskrima in the Philippines, and in the highest levels of Okinawan karate. They are generally regarded as the most advanced techniques in the martial arts.

Practising forms

When the techniques have been practised, the master leads his students on to the practice of forms. These are prearranged sequences of movement that the student must repeat continually until he or she can exe cute them perfectly. Each form lasts for about a minute and incorporates 20 to 50 essential techniques. After repeated practice, the students know the forms so well that when faced with an opponent they perform the techniques contained within the forms almost instinctually.

The student moves in straight lines forward and backward and from side to side, using steps of advance, retreat, evasion and so on to link the techniques into one flowing movement, which traces the form of a cross or a square.

Forms, called suvadu in South India, begin and end with a salutation. They are beautiful to watch. Certain techniques may be mirrored, or repeated in different directions. So, if you have just stepped forward to the east on the right leg and punched and blocked with the right arm, the next move may be to turn round, step forward to the west on the left leg and punch and block with the left arm.

In kalaripayit, empty-handed forms can also be reproduced exactly, holding any weapon in the hand. Practising forms with an opponent will produce a paired form of mock combat. This is choreographed, and is therefore entirely different from free-form fighting, in which students are free to use whatever movements and techniques they want as long as they refrain from hurting each other.

Forms are used extensively in many Chinese and Japanese martial

arts. Some Chinese forms are known to have reached South India centuries ago. Typical of these forms are hand movements which are much more rapid and complicated than the Indian forms. To a trained eye they are recognizably Chinese, although they are far from exact copies of Chinese forms. ;

Forms are intended to instil self-discipline in the performer and to improve balance, timing and precision. Many of the kalaripayit forms involve executing spectacular leaping turns, feints, or sham attacks to divert attention or deceive the opponent, ducking beneath kicks and jumping over strikes. Besides the traditional northern and southern forms are those that individual masters sometimes develop for use with weapons.

Training with sticks

Practice with stick and staff, called silambam in South India, is almost a separate martial art. Recently steps have been taken to establish sporting tournaments and competitions in order to encourage a separate stick art, but kalaripayit masters still teach it in traditional form as part of their syllabus.

Throughout Asia the staff and stick have always been popular defensive weapons. A stick, the traditional traveller's said, is light and inconspicuous, and presents no immediate threat to another person. As a weapon, however, it is cheap and easy to acquire, strong and durable, and can be used in many different ways. A staff or stick provides an excellent defence against all but projectile weapons. Most staffs, even those made of rattan and bamboo, will stand up quite well even to sharp-edged blades; indeed, it is possible to knock a metal blade from an opponent's hand, or even to break it, using a stick or staff.

Stick and staffs also make excellent training weapons. They are blunt, but inflict sufficient pain to deter apathy in the trainee. Cut to the appropriate lengths they can be made to represent knives, swords, spears, halberds and so on, which can be wielded with ease. They have special advantages in combat since they may be used to stun, immobilize or hurt an opponent without causing serious injury. It is for this reason that they are the chosen weapon of so many of the world's police forces.

Indian silambam sticks range in size from about,15 centimetres (six inches) to a little less than two meters (six feet). Most students use sticks made from rattan, which is quite flexible, but advanced students use hardwood staffs.

The longer weapons are usually held with one hand grasping the centre and the other holding one end. It is a characteristic of Indian fighting, however, that the stick may be grasped with both hands at one end only, and wielded rapidly, so that blows are showered on the opponent. Blocking is often effected by holding the stick with each hand one-third of the way along its length.

Low stances and a rapid fire of blows and blocks typify silambam techniques. Single and paired stick forms are studied first, followed by free sparring, usually between master and student.

Training with weapons

Many stick techniques can be used in conjunction with the other weapons of kalaripayit. One simple weapon, fashioned from two pairs of deer horns tied together, has two sharp stabbing points, and is also excellent for blocking. The Indian dagger, known as Bundi in most parts of the sub-continent, is also excellent for blocking because of its unique handle. Bundis may be used singly, or in pairs.

Swords, with blades about 65 centimetres (26 inches) long are commonly used by themselves, in pairs or with a buckler or shield. Other kalaripayit weapons include various types of spear, trident and battle axe. There is also an array of improvised weapons such as knife swords made from the noses of sword-fish, and even three-directional knives, that is, knives with three blades, each pointing in a different direction.

The urumi or spring-sword is perhaps the most spectacular Indian weapon. It is made from two or three bands of metal, each about four centimetres (two inches) wide and two meters (six feet) long, joined at one end to a wooden handle. It is difficult and dangerous to use, but, when mastered, is a most effective means of beating off an attack from many people.

Staffs whose ends are fitted with heavy, wooden balls may be used as flying weights, rather like the European mace. Alternatively, they may be covered in rags, soaked in oil, and set alight to frighten and deter opponents. This weapon may have originated in ancient times when fire was used to try to break up the charge of elephants in battle.

Many kalaripayit weapons are reminiscent of medieval weapons. Both the weapons and the techniques for using them may have originated on the battlefield. However, today kalaripayit is more often displayed on ceremonial and festive occasions than in battles, and this has led to an emphasis upon spectacular techniques and weapons, some of which are of questionable martial use. Most of the other techniques in current use are, however, fearsome and efficient.

The medical lore of the masters

As senior students complete their rigorous and extensive training in kalaripayit, some may seek to penetrate deeper into the wisdom and knowledge of their masters. Only a few carefully chosen students are allowed to follow this course, but either or both of two paths exist for those permitted to choose them. Both are concerned with a deepening intimacy with the workings of the human body, and there is a sense in which the two are complementary. On the one hand there is the path to medicine and healing in the great Ayurvedic tradition. On the other there is the way to the secret martial art of marma-adi, the striking of the vital points of the body.

The master, also traditionally the local doctor in this as in every

martial art, must treat not only the simple injuries, such as bruises and strains to muscles and joints, sustained by students during practice, but occasionally a nerve centre that has been jarred, or a fractured bone. More rarely a student or performer sustains internal injuries to the abdomen or another part of the body. After years of treating a wide variety of injuries he becomes increasingly expert in medical knowledge.

Moreover, in a more strictly martial sense, the Indian masters of kalaripayit have access to a venerable body of medical knowledge first recorded in the sastras, ancient Buddhist texts or treatises that were written upon palm-leaf pages and handed down from master to student.

The Susruta-Samhita, a medical sastra dating from between the second and fourth centuries AD, and written by the Indian physician and surgeon, Susruta, contains specific information about 107 or 108 spots on the body which, when struck, pierced or just squeezed forcibly, will result in temporary paralysis, extreme pain, loss of consciousness or even immediate or delayed death.

These vital points are thought in India to be the junction points of blood vessels, ligaments and nerve centres. Each spot is located in a precisely defined area of the body which may be tiny and difficult to isolate, and must be struck in a particular fashion and with specific force. Only the most advanced practitioners of the art are therefore capable of using this knowledge effectively.

All masters guard every closely their knowledge of the vital points; those whom we met made it clear to us that the little they were prepared to pass on to us should be treated with the utmost respect. For this reason we have reproduced only photographs showing the striking of vital points at spots that are well-known danger points in such disciplines as boxing as well as the martial arts. Targets such as the temple, the sternum, the jugular vein and the testicles are known to most fighters as highly vulnerable points. There is however, a large number of less well known spots which can be used to disable still more effectively.

Many readers may remain cynical about our reticence on this subject. However, hidden in the annals of forensic scientists, both English and Asian, are fully documented details of what will happen to anyone. struck on one of these spots. It is out of respect for the masters and not because of doubts about the validity of the information, that we mention little in this book about the lore of vital points. Those who wish to

know more must study diligently for many years before any master will trust them with such deadly information.

The secret system of marma-adi adds to the evidence of the depth and antiquity of kalaripayit. It brings the art into line with the most esoteric of its Chinese and Japanese counterparts, which also contain secret knowledge of a deadly nature. Experts, who have compared the locations of the vital spots revealed in ancient Indian texts with the locations known to the practitioners of the modem Chinese and Japanese arts, have found a high degree of correlation.

In accordance with the martial arts tradition, masters of marma-adi in South India know how to resuscitate anyone who has been struck on one of the vital spots. They do this by massage, bone and joint manipulation and the use of herbs and poultices. It is not surprising that they should have gained such knowledge, since occasionally, during training, a student is struck accidentally on a vital spot.

One aspect of the system that is almost unique to South India is that there exist a few men who are masters of marma-adi alone, and who do not practise any other form of martial art.

Ways of controlling elephants

Animals as well as humans have vital spots, many of which are familiar to the Indians. The elephant is known to have 90. By prodding one spot with a sharp stick, the mahout or rider can command his elephant to trumpet; poking another will make it kneel or lie down, turn round, go forward, and so on. There are six spots which, if prodded in a particular way, will frighten an elephant, one which will benumb it and four teen which will cause the animal's immediate death.

***

VASUDEVAN GURRUKAL

Vasudevan Gurrukal, Master of the northern style of kalaripayit, talked to us about his kalari or training ground:

"In ancient times big landlords had their own kalaris. In the course of time, if they were not used for practice of kalari, they would not demolish them. But instead, they were converted into temples.

Even if there are no students to practise, a kalari will never be demolished. A sacred lamp will be lit there every day. If there is anyone with good knowledge of kalaripayit they will be able to use it, but if there is no-one to use it, the kalari will remain surrounded by trees, shrubs and creepers. Here it was so when I came. "

Then the Master spoke of the importance of students in kalaripayit:

"The students should be of obedient nature. If they fight with others inside or outside the kalari we expel them at once.

The kalari can be compared with the body of a human being and the students are like the spirit of the being.

Without the body, the spirit cannot exist; without the kalari, the students cannot be.

The students cannot study except in the kalari. Without it, they would be like the spirit which is without the body. Similarly, kalaripayit without the students is useless. It is like the body without spirit. Both are essential.

Students must respect the Goddess of war. Kali, and always show respect to their master. That is where our strength of mind comes from. If we receive the blessings of our master and the Goddess Kali, we receive power. It becomes our habit and we have faith in it. We believe that we get power from our master and the Goddess. Sometimes students will engrave the mantras (sacred passages, usually from the Vedas, the Hindu scriptures) on a piece of metal and carry this around, or tie it around the wrist with a small packet of turmeric powder, kumkum, camphor, or some other medicinal herb, twisted into a kind of bangle.

When I begin teaching a student with a stick or a weapon I pray that he should not use this thing for any evil purpose, that no ill should befall him because of it and that it should be a protection for him from all evil forces.

But whatever the guru teaches, it will add up to only one quarter of that student's knowledge. A quarter he derives from his own personal interest, and from hard work; a quarter comes from God's blessing, and the final quarter comes in his old age from his own personal experiences. "

Finally, the Master spoke of the moral responsibility of a trained student of kalaripayit:

"We must forgive our enemy. Also, it is our duty to safeguard our families. If we want we can easily kill a man, but we may have to go to jail, and that will affect our families. So we must think of our families, and our enemies' families, and avoid fights, forgive enemies. It is easy to strike a person and to fight, but it doesn't enable us to escape from our responsibilities."

***

MATHAVANASAN

Mathavanasan, Master of the southern style, chose to explain to us his teachings by relating some of the crucial points in his own experiences of learning kalaripayit, and the associated manna medical systems on which he now concentrates.

"When I was six years old, I went with my father to see a festival at which his basic and advanced students were giving a demonstration of kalaripayit techniques. We were standing at the side, near the back, and because I was a small boy, I could not see what was going on. My father lifted me on to his shoulder and went up to the front, near the stage. When the people who had organised the show saw him, they gave him a seat beside the guests and honoured him. Then was the first time in my life that I wanted to learn kalaripayit.

That day, after the festival, when we were returning home, I asked my father about kalaripayit. What is this? They performed fights with sticks, and wrestling didn't that hurt them? Such were the questions I asked. He said that if we learn the art fully, we will not feel pain. The sticks of others will not fall on our bodies. We can keep our bodies healthy and in good condition by learning the techniques.

So I started learning this art under the guidance of my father, uncles and their friends and students. I continued the studies for years. While I was doing my higher schooling, I studied the sastras, the philosophy behind the higher techniques.

I inherited the post of physician from my grandfather and my father.

They were marma physicians, and they used to spend most of their time in the field of kalaripayit treatment. I acquired a good knowledge from them, and then went to study further. This background enables me to work with greater confidence, and that brings mental peace.

I do not want to be a very rich man. I just want mental peace. Helping those people who suffer from pain, and those who do not want to live in this world because of some severe illness, is giving me satisfaction. It was for this reason — to help others — that I studied and specialised in marma treatment. It is more difficult than any other medical system. We study the whole body, to understand its system, functions, differences and defects. There is no other study as clear as this one.

I have never studied any other science. Manna is a vast subject, a great and endless science.

The man who has studied marma and kalaripayit techniques should be a useful person to society. He must possess traits such as reverence, civility, humility, patience, self-control, obedience, and kindness towards others. He should be an example to others. This does not apply only to men, for women too should be like this. The masters of this art and marma physicians should never do wrong to others, but should help people. This is the way they should lead their lives.

One thing more you must know. If an enemy comes to attack you, you must keep quiet for some time. You must think well and calmly. Within this time your mind will have some peace, and that peace of mind is the most important thing. If an enemy comes, fighting with him, overcoming him and killing him is not the important thing. That any body can do. If instead of fighting with him you say to your enemy "you have won " and bow before him, that is the biggest deed in the world."

_______________________________

from Howard Reid and Michael Croucher,

Martial Arts,

Eddison/Sadd Editions Ltd,

1983.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet