Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist - The Story of Abraham Lincoln - Chapter II

Chapter II

Awakening

Acouple of years later, things changed to revive Lincoln's sagging interest in politics. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska bill was introduced by Senator Stephen Douglas. It proposed to organize large tracts of land on the west of Missouri into two territories1 for settlers and for a Midwestern Transcontinental Railroad. He advocated popular sovereignty, which would leave the decision to permit slavery or not to the mandate of the people of each state. Douglas claimed that personally he was indifferent to the issue of slavery and believed that it would be in the interest of the nation to allow people of each state to choose democratically for themselves to be a free or slave state.

1. Land west of Missouri was part of the Louisiana territory wherein the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had prohibited slavery north of the parallel 36:30 degrees north except within the boundaries of the proposed state of Missouri which came in as a slave state.

Douglas likened the Kansas-Nebraska Act (see Map p. XII-B) to the Compromise of 1850, where the issue of free or slave state was left to popular sovereignty in Utah and New Mexico. He argued that the Missouri Compromise1 of 1820 was not being violated, it was being ignored since the mandate to be a slave or free state would be given to the citizens of the states. However, anti slavery factions did not agree with him; they felt betrayed since Kansas-Nebraska Act violated the Missouri Compromise that had banned slavery in both these territories and declared that all states north of 36:30 latitude would in the future be free states; it would open those very doors again to slavery through popular sovereignty. However, little did Douglas realise that this very act would be the cause of the greatest conflict in the country leading to the Civil War, causing the death of thousands of its soldiers.

By 1854, Lincoln's interest in politics had almost been overshadowed by his law profession. But the Kansas-Nebraska Act, passed in 1854 after months of debates in both houses, repealing the Missouri Compromise of 1820 'aroused him as he had never been before. '2

Lincoln was opposed to slavery, but he felt that it would be wiser to prevent any further expansion of slavery to other states, and gradually over time and through a mandate of the people eradicate slavery from each slave state (as he had suggested in the case of British Columbia). He did not agree with the abolitionists who wanted to end slavery immediately. He had doubts whether the white people and Negroes could co-exist peacefully with each other, given the racial incompatibility created over a hundred years. He feared that this Act would reverse the effort to contain slavery and might revive the African slave trade that would turn America into a massive slave empire.

Douglas addressed the people with the aim to defend the

- Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which Missouri was admitted as a slave state, Maine was admitted as a free state and states north of 36:30 degrees north latitude would be admitted into the union as free states.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings ( 1859-1865), Autobiography Written for Campaign, page 154

Kansas-Nebraska Act at Springfield with great confidence and the next day Lincoln replied, directly criticizing the Kansas—Nebraska Act:

"My distinguished friend says it is an insult to the emigrants to Kansas and Nebraska to suppose they are not able to govern themselves... I admit that the emigrant to Kansas and Nebraska is competent to govern himself, but I deny his right to govern any other person without that person's consent."1

This statement revealed the root of the matter and the gulf between the position of Douglas and Lincoln. Lincoln's clarity in expression allowed the audience to see the immorality of `Popular Sovereignty'.

Douglas addressed the people defending the Kansas-Nebraska Act at Peoria. On 16th October 1854, Lincoln responded with his famous Peoria speech:

"... It is wrong; wrong in the direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska – and wrong in the prospective principle, allowing it to spread to every other part of the wide world, where men can be found inclined to take it.

"This declared indifference, but I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I cannot but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself... it deprives our republican institutions to taunt us as hypocrites...the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity...it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticizing the Declaration of Independence and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest...

1. The Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Henry Raymond, page 21

"If all earthly power were given to me, I should not know how to do, as to the existing institution [of slavery]. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves and send them to Liberia – to their own native land. But a moment's reflection would convince me...its sudden execution is impossible. If they all landed there in a day, they all perish in the next ten days...Free them and make them politically and socially our equals? My own feelings will not admit this; and if mine did, we know that those of a great mass of white people will not. Whether this feeling accords with justice and sound judgment is not the sole question, if indeed it is part of it. A universal feeling, whether well or ill-founded, cannot be safely disregarded. We cannot then, make them equals. It does seem to me that systems of gradual emancipation might be adopted; but for their tardiness in this, I will not undertake to judge our brethren of the south...

"The doctrine of self-government is right – absolutely and eternally right – but it has no just application, as here attempted... When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself, and also governs another man, that is more than self-government—that is despotism. ...What I do say is, that no man is good enough to govern another man, without the other's consent... Our Declaration of Independence says:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, DERIVING THEIR JUST POWERS FROM THE CONSENT OF THE GOVERNED."

"...But Nebraska is urged as a great Union-saving measure.

Well I too go for saving the Union. Much as I hate slavery, I would consent to the extension of it rather than see the Union dissolved, just as I would consent to any GREAT evil, to avoid a GREATER one. But when I go to Union saving, I must believe, at least, that the means I employ has some adaptation to the end. To my mind, Nebraska has no such adaptation.

"... Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man's nature — opposition to it is in his love of justice...repeal all past history, you still cannot repeal human nature...

"...Near eighty years ago we began by declaring that all men are created equal; but now from that beginning we have run down to the other declaration, that for SOME men to enslave OTHERS is a 'sacred right of self-government.'...Let us return to the position our fathers gave it... Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence. We shall have so saved [the Union], that the succeeding millions of free happy people, the world over, shall rise up, and call us blessed, to the latest generations."1

He toured the state giving speeches to awaken the people to the injustices of the Act and enlighten them towards their duty towards the preservation of the union. Contrary to Douglas' advice to the people, he insisted that whether the territories came in as slave or free states did affect the entire country since slave states had an advantage over free states in the Senate and House of Representatives.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act led to the emergence of the Republican Party in July 1854, founded by ex-Whigs and other antislavery activists. It was a merger of various groups, which were united by their passionate opposition to the expansion of

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Act at Peoria, Ill, p. 307

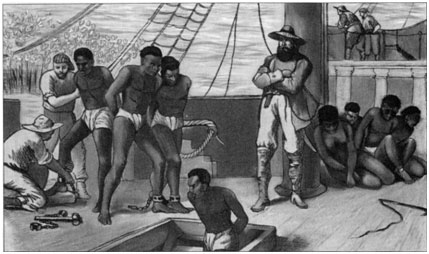

Slaves being taken on a boat for trade

slavery. It soon became the most dominant political Party in the North.

In November 1854 Lincoln won the election to the Illinois House of Representatives on the Whig ticket but declined it. He felt it was time to make a bid for the Senate where he would be able to make a bigger difference.

The political parties too were going through a transition. The Southern Whigs had broken off from the main party and joined the Democratic Party. A faction of the Democratic Party broke off and formed the Anti-Nebraska Democratic Party. Here again we see how the greater interest of the nation superceded Lincoln's own personal ambitions. The Whigs nominated Lincoln, the Anti-Nebraska Democrats nominated Lyman Trumball and the Democrats nominated Governor Matteson for the Senate. Lincoln did not want Governor Matteson to win since his stance on the subject of slavery was questionable. The only way possible was if the Whigs joined hands with the Anti-Nebraska Democrats. Since the Anti Nebraska Democrats were unwilling to sacrifice their nominee, he requested his friends to vote for Lyman Trumball instead of himself. This decision proved to be

the right one; in time to come the new Republican Party would gather all these forces under its umbrella and choose Lincoln to stand at the helm.

Though Lincoln hated slavery, he was opposed to any unlawful opposition to it. The newly formed Abolitionist Party decided to come to assist the anti slavery faction in Kansas. Lincoln, answered in response to their cry for 'Liberty, Justice, and God's higher law':

"Friends, you are in the minority — in a sad minority; and you can't hope to succeed, reasoning from all human experience. You would rebel against the Government, and redden your hands in the blood of your countrymen. If you have the majority, as some of you say you have, you can succeed with the ballot, throwing away the bullet... Let there be peace... Revolutionize through the ballot-box, and restore the Government once more to the affection and hearts of men, by making it express, as it was intended to do, the highest spirit of justice and liberty. Your attempt, if there be such, to resist the laws of Kansas by force, will be criminal and wicked; and all your feeble attempts will be follies, and end in bringing sorrow on your heads, and ruin the cause you would freely die to preserve."1

Since the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened up the territories, wagonloads of people moved into Kansas. Since it shared its border with Missouri, slaveholders from Missouri wanted Kansas also to be a slave state and felt threatened by the emigration of freeholders in Kansas. Both factions had aspirations to control the state policy; Slaveholders set up their convention in Lecompton and free-soilers chose Topeka as their headquarters. Slaveholders wanted to ensure that slavery is voted up by any means and resorted to corrupt measures and even violence to ensure that Kansas be brought in as a slave state. Polls were

1. The Every-Day Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Francis F. Brown, p. 158

conducted that were completely controlled by proslavery hooligans of Missouri. President Franklin Pierce too supported the entry of Kansas as a slave state. Very soon there were skirmishes between the two factions. In 1856, a proslavery group ransacked a free soil stronghold, burned down a hotel and destroyed homes and shops. In retaliation, John Brown, an abolitionist killed a group of proslavery men. For months these two groups fought each other, destroying property and taking lives. What was purported to be a democratic Act was disintegrating into mayhem.

The violence and the corrupt politics in Kansas outraged the north and the antislavery faction and led to a rising of the tide against the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It reached the Congress; senators of several Northern states vehemently criticized Douglas' Act; Democrat Preston Brooks physically attacked Charles Sumner1 after he delivered a sharp criticism of the Act in the Senate. The country was beginning to fall apart.

Unable to support the Whigs any further, in 1856, Lincoln joined the Republican Party, whose platform was expansionism and opposition to popular sovereignty. John C. Fremont was announced as their first presidential candidate. Lincoln campaigned fervently for the presidential elections and resultantly the Republican Party gained substantial support in the Northeast. But some southern politicians threatened to secede from the union if Fremont won the presidency, therefore, Democrat James Buchanan, won the election and was sworn in as President in 1856. Despite the Republicans losing the election, Lincoln had become a familiar and popular name in the North.

Kansas was still controlled politically by the proslavery faction despite the fact that free-soilers outnumbered them. President James Buchanan, like his predecessor, was a southern sympathizer and wanted Kansas to enter the union as a slave state. But Douglas objected since it violated his idea of Popular Sovereignty; it was the people of the state who ought to decide. Once again polls ensued, were indecisive, and the

1. Anti slavery leader of the Republican Party

mayhem went on.

The issue of slavery was beginning to reach a crescendo; the Dred Scott Decision of 18571 angered the anti slavery faction even more and galvanized the Republican Party for the next elections. Further, the Fifth Amendment spelled out that no person could be deprived of 'life, liberty or property (which included slaves) without due process of the law'; this made the Federal government powerless to prohibit the practice of slavery anywhere in the Union, even in free states where slavery was banned.

It was a severe setback for the abolitionists and the antislavery faction and appeared to be a momentous triumph for the south. But the Dred Scott Decision also challenged the sanctity of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which advocated that the people of the state have the right to decide whether they want a free state or a slave state. The powerlessness of the Federal Government corresponded to the powerlessness of the state governments. The Dred Scott Decision rendered the principle of popular sovereignty null and void and Douglas was hard-pressed to reconcile both.2

Criticising the Dred Scott Decision, Lincoln said:

"... In those days, our Declaration of Independence was held sacred by all, and thought to include all; but now, to aid in making the bondage of the Negro universal and eternal, it is assailed, and sneered at, and construed, and

- Dred Scott, a slave, who had been brought by his master to live in Illinois, a free state, had sued for his freedom on the grounds that according to the Missouri Compromise, after living in a free state for a fixed number of years, legally he could not be returned to slavery. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (influenced by President Buchanan's pro slavery views) passed a judgment that since the Constitution gave no rights to a slave, Scott could not present a case in a Federal court. Also, the Fifth Amendment spelled out that no person could be deprived of "life, liberty or property without due process of the law," and since slaves were termed as property, the Federal government was powerless to prohibit the practice of slavery anywhere in the Union, even in free states where slavery was prohibited. This meant that someone from a free state could go to a pro slavery state, buy a slave and bring him back to a free state and keep him there as a slave. It amounted to a violation of the constitutional rights of the free states.

- See previous footnote

hawked at, and torn, till, if its framers could rise from their graves, they could not at all recognize it...." 1

At the Republican Party Convention at Springfield, which nominated Lincoln for the Senate in 1858 he gave his famous house divided speech:

"... If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. 'A house divided against itself cannot stand.' I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new — North as well as South.

"Have we no tendency to the latter condition? ...

"The result is not doubtful. We shall not fail — if we

stand firm, we shall not fail. Wise counsels may accel-

erate or mistakes delay it, but sooner or later the victory

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Speech on the Dred Scott decision at Springfield, Illinois, June 26th 1857, p. 390

is sure to come."1

With these words reflecting his inner conviction and strength of purpose, he closed his speech. Lincoln had deliberately quoted from the bible; on the evening previous to delivering his speech, he had read out his speech to Herndon.

"Mr. Herndon was startled at its boldness. "I think," said he, "it is all true. But is it entirely politic to read or speak it as it is written?" "That makes no difference," said Lincoln. "That expression is a truth of all human experience, — 'a house divided against itself cannot stand.' The proposition is indisputably true, and has been true for more than six thousand years; I want to use some universally known figure, expressed in simple language, that may strike home to the minds of men in order to rouse them to the peril of the times."2"

He also wanted people to realize that despite Douglas' statement that he was indifferent to the issue of slavery, he covertly was in favour of slavery and ought not to be trusted with the task of keeping the union from falling apart:

"...This was their lofty, and wise, and noble understanding ... they knew the tendency of prosperity to breed tyrants, and so they established these great self-evident truths... While pretending no indifference to earthly honors, I do claim to be actuated in this contest by something higher than an anxiety for office... I am nothing; Judge Douglas is nothing. But do not destroy that immortal emblem of Humanity — the Declaration of American Independence."3

- Lincoln Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), 'House Divided' speech addressing his Republican colleagues in Springfield, 16th June 1858, p. 426

- The Every-Day Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Francis F. Brown, chapter XI, p. 178

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 2, edited by Roy Basler, Speech at Lewistown, Illinois, on 17th August 1858, p. 544

Douglas, knowing that in Illinois there was a deep-seated universal prejudice against the Negro, constantly misrepresented Lincoln in his reference to the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln responded:

"My declarations upon this subject of Negro slavery may be misrepresented, but cannot be misunderstood. I have said that I do not understand the Declaration to mean that all men were created equal in all respects...Certainly the Negro is not our equal in color, perhaps not in many other respects; still, in the right to put into his mouth the bread that his own hands have earned, he is the equal of every other man, white or black."1

When Douglas had heard of Lincoln's nomination, he had remarked anxiously:

"I shall have my hands full. He is the strong man of the party — full of wit, facts, dates — and the best stump speaker, with his droll ways and dry jokes, in the West. He is as honest as he is shrewd, and if I beat him my victory will be hardly won."2

Lincoln's 'house divided' speech had a great impact on the people of the North about slavery dividing the Union. He then invited Douglas to engage in a series of public debates with him in their state (see Map p. XIII). He wanted to improve his position among the people. They faced each other seven times over three months in front of large crowds, sometimes upto fifteen thousand people. These Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 drew the attention of the entire nation. The press covered these debates comprehensively and the nation could follow the evolution of the campaign.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), Speech at Springfield on 17th July 1858, p. 460

- A. Lincoln: A Biography, by Ronald C. White, Jr., p. 258

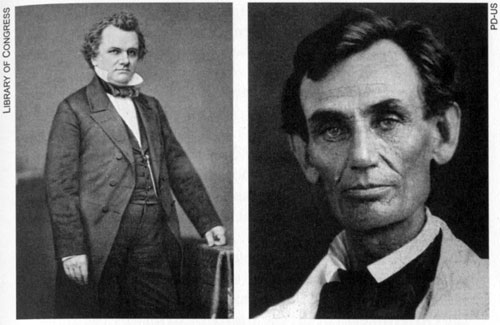

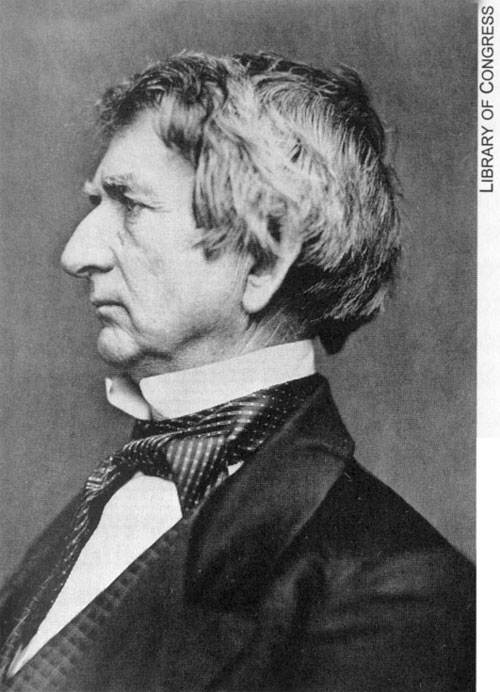

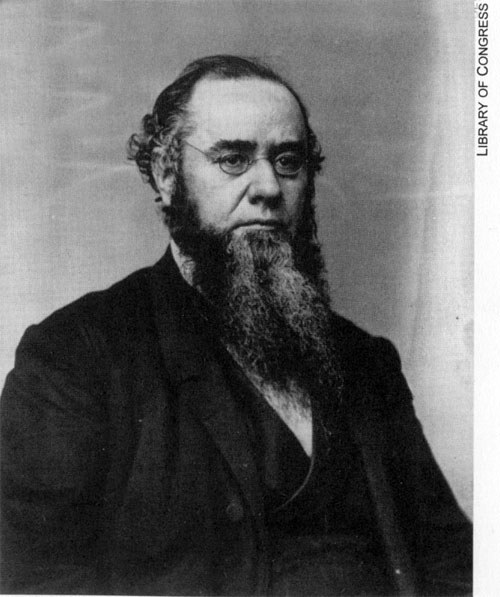

The contenders in the debates of 1858 - Left: Stephen Arnold Douglas, and right: Lincoln

The contenders in the debates of 1858 - Left: Stephen Arnold Douglas, and right: Lincoln

The two were complete antithesis of each other — Douglas was short in front of Lincoln's towering frame, he was a known figure in the country while Lincoln enjoyed only a local reputation, Douglas was short and stocky, dressed in fancy clothes while Lincoln was thin and tall and plainly dressed. Douglas, a strong and formidable contestant, known as the 'little giant' was an outstanding orator with a booming voice, while Lincoln was ungainly on the podium and his voice often became high pitched when he spoke. Douglas was a former judge of the Supreme Court of Illinois and had been a sitting senator since 1847.

These debates revolved around the subject of slavery; Douglas asserted the superiority of the white man while Lincoln referred to the Declaration of Independence that 'all men are equal'. He attacked Douglas on three issues: he insisted that slavery was wrong and the nation could not permanently exist part slave and part free, that the doctrine of Popular Sovereignty that essentially suggests that if one man chooses to enslave another,

no third man can intervene or object was wicked and that there existed a conspiracy to perpetuate slavery in the entire nation, a part of which were the Dred Scott decision and the Kansas-Nebraska bill.

At Quincy Lincoln closed his speech with the following remarks:

"... Judge Douglas asks you, `Why cannot the institution

of slavery, or, rather, why cannot the nation, part slave and part free, continue as our fathers made it forever?' In the first place, I insist that our fathers did not make this nation... part slave and part free. I insist that they found the institution of slavery existing here. They did not make it so, but they left it so, because they knew of no way to get rid of it at that time... More than that; when the fathers of the Government cut off the source of slavery by the abolition of the slave-trade, and adopted a system of restricting it from the new Territories where it had not existed... it was in the course of ultimate extinction; and when Judge Douglas asks me why it cannot continue as our fathers made it, I ask him why he and his friends could not let it remain as our friends made it?"1

At Alton, he began by saying:

"...What is it that we hold most dear among us? Our own liberty and prosperity. What has ever threatened our liberty and prosperity, save and except this institution of slavery? If this is true, how do you propose to improve the condition of things by enlarging slavery? — by spreading it out and making it bigger? You may have a wen or cancer upon your person, and not be able to cut it out lest you bleed, to death; but surely it is no way to cure it to ingraft

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1832-1858), 6th debate at Quincy, Illinois, 13th October 1858, p. 730

it and spread it over your whole body — that is no proper way of treating what you regard a wrong. This peaceful way of dealing with it as a wrong — restricting the spread of it, and not allowing it to go into new countries where it has not already existed — that is the peaceful way, the old-fashioned way, the way in which the fathers themselves set us the example. Is slavery wrong? ... They are two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time; and will ever continue to struggle. The one is the common right of humanity, and the other the divine right of kings... 'You work, and toil, and earn bread, and I'll eat it.' No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men... for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle."1

Lincoln stressed on the morality of the issue while Douglas stuck to the legality of the issue of slavery. However, in Douglas' hometown Freeport, Lincoln decided to confront him on legal grounds. Since the Dred Scott Decision rendered the principle of popular sovereignty null and void, how could Douglas support both these conflicting views?

Douglas dismissed the Supreme Court verdict as irrelevant since according to the Act, people of a state had a right to self govern and choose to allow slavery or not in their state by electing representatives to the legislature who would establish regulations that would either permit or ban slavery in that territory or state. Such strong words did not go down well in the national media. They felt he was validating mobocracy over the law of the country. But Illinois was still strongly in favour of state rights; in 1858 Douglas won the Senate seat narrowly from Illinois.

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings ( 1832- 1858), 7th debate at Alton, Illinois, 15th October 1858, p. 774

The Ascent To The Top

Despite his disappointment, Lincoln continued to rise as a national figure and emerged as a strong Republican Party leader. He went back to his profession; politics had kept him away from his livelihood and he needed to earn money.

The Kansas turmoil resulted in a crack in the Democratic Party between the proslavery Southern states and the antislavery Northern states. The Republican Party reaped the benefit of this split and in the midterm elections of 1858 had secured seats in the northern and western states, thereby strengthening their position as the opposition party.

In September 1859 when he heard that Senator Douglas was going to address people in Cincinnati, Ohio, he agreed to give a speech there as well. Speaking to the Kentuckians (slaveholders) in the audience he said:

"...I think slavery is wrong, morally and politically. I desire that it should be no further spread in these United States, and I should not object if it should gradually terminate in the whole Union.

"While I say this for myself, I say to you Kentuckians, that I understand you differ radically with me upon this proposition; that slavery is right; that it ought to be extended and perpetuated in this Union. Now, there being this broad difference between us I do not pretend in addressing myself to you, Kentuckians, to attempt proselyting you; that would be a vain effort...

"What do you want more than anything else to make suc-

cessful your views of Slavery, — to advance the outspread

of it, and to secure and perpetuate the nationality of it?...

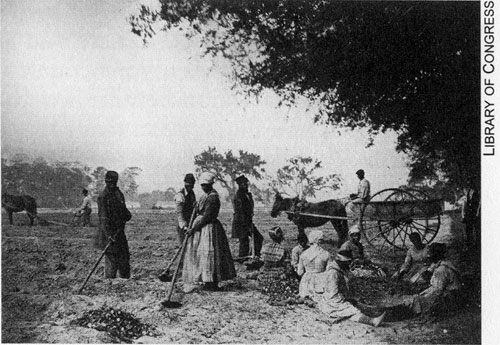

Slaves working on a southern plantation

What is indispensable to you? Why! if I may be allowed to answer the question, it is to retain a hold upon the North — it is to retain support and strength from the Free States. If you can get this support and strength from the Free States, you can succeed. If you do not get this support and this strength from the Free States, you are in the minority, and you are beaten at once.

"... I will tell you, ... what we mean to do with you. We mean to treat you as near as we possibly can, like Washington, Jefferson and Madison treated you. We mean to leave you alone, and in no way to interfere with your institution; to abide by all and every compromise of the constitution... We mean to recognise and bear in mind always that you have as good hearts in your bosoms as other people, or as we claim to have, and treat you accordingly.

" ... I want to know, now... what you mean to do. I often hear it intimated that you mean to divide the Union whenever a Republican, or anything like it, is elected President of the United States.

"Well, then, I want to know what you are going to do with

your half of it? ... are you going to keep it right alongside of us outrageous fellows? Or are you going to build up a wall some way between your country and ours... You have divided the Union because we would not do right with you as you think, upon that subject; when we cease to be under obligations to do anything for you, how much better off do you think you will be? Will you make war upon us and kill us all? Why, gentlemen, I think you are as gallant and as brave men as live... but being inferior in numbers, you will make nothing by attempting to master us."

Then addressing the entire audience of Ohio he said:

"It is a favorite proposition of Douglas' that the interference of the General Government, through the Ordinance of `871, or through any other act of the General Government, never has made or ever can make a Free State; that the Ordinance of '87 did not make Free States of Ohio, Indiana or Illinois. That these States are free upon his 'great principle' of Popular Sovereignty, because the people of those several States have chosen to make them so.

"Pray what was it that made you free? What kept you free? Did you not find your country free when you came to decide that Ohio should be a Free State? ... Let us take an illustration between the States of Ohio and Kentucky... Kentucky is entirely covered with slavery — Ohio is entirely free from it. What made that difference? Tell us, if you can... if there be anything you can conceive of that made that difference, other than that there was no law of

1. The Northwest Ordinance was adopted by the Confederation Congress on July 13, 1787. It established a government for the Northwest Territory, defined the process for admitting a new state to the Union, and promised that newly created states would be equal to the original thirteen states. The Northwest Ordinance also protected civil liberties and outlawed slavery in the new territories.

any sort keeping it out of Kentucky?1 While the Ordinance of '87 kept it out of Ohio.

Illinois and Missouri came into the Union about the same time, Illinois in the latter part of 1818, and Missouri, after a struggle, I believe some time in 1820. At the end of that ten years, ... the number of slaves in Illinois had actually decreased; while in Missouri, beginning with very few, at the end of that ten years, there were about ten thousand.

"... in Missouri there was no law to keep that country from filling up with slaves, while in Illinois there was the Ordinance of '87. The Ordinance being there, slavery decreased during that ten years — the Ordinance not being in the other, it increased from a few to ten thousand. Can anybody doubt the reason of the difference?

"I think all these facts most abundantly prove that my friend Judge Douglas' proposition, that the Ordinance of `87 or the national restriction of slavery, never had a tendency to make a Free State, is a fallacy — a proposition without the shadow or substance of truth about it.

"Douglas looks upon slavery as so insignificant that the people must decide that question for themselves, and yet they are not fit to decide who shall be their Governor, Judge or secretary, or who shall be any of their officers. These are vast national matters in his estimation but the little matter in his estimation, is that of planting slavery there. That is purely of local interest, which nobody should be allowed to say a word about.

1. Ohio was a part of the Northwest Territory under the Ordinance of 1787, which outlawed slavery; Kentucky was a territory under no law that kept slavery out.

"Labor is the great source from which nearly all, if not all, human comforts and necessities are drawn... Some men assume... that nobody works unless capital excites them to work. They begin next to consider what is the best way. They say that there are but two ways; one is to hire men and to allure them to labor by their consent; the other is to buy the men and drive them to it, and that is slavery. Having assumed that, they proceed to discuss the question of whether the laborers themselves are better off in the condition of slaves or of hired laborers, and they usually decide that they are better off in the condition of slaves.

"In the first place, I say, that the whole thing is a mistake. That there is a certain relation between capital and labor, I admit. That it does exist, and rightfully exists, I think is true. That men who are industrious, and sober, and honest in the pursuit of their own interests should after a while accumulate capital, and after that should be allowed to enjoy it in peace, and also if they should choose when they have accumulated it to use it to save themselves from actual labor and hire other people to labor for them is right. In doing so they do not wrong the man they employ, for they find men who have not of their own land to work upon, or shops to work in, and who are benefited by working for others, hired laborers, receiving their capital for it. Thus a few men that own capital, hire a few others, and these establish the relation of capital and labor rightfully. A relation of which I make no complaint. But I insist that that relation after all does not embrace more than one-eighth of the labor of the country."

He added that 'the hired laborer with his ability to become an employer, must have every precedence over him who labors under the inducement of force'. He continued:

"Whoever desires the prevention of the spread of slavery and the nationalization of that institution, yields all, when he yields to any policy that either recognizes slavery as being right, or as being an indifferent thing... This government is expressly charged with the duty of providing for the general welfare. We believe that the spreading out and perpetuity of the institution of slavery impairs the general welfare. We believe — nay, we know, that that is the only thing that has ever threatened the perpetuity of the Union itself... Our friends in Kentucky differ from us.

"I say that we must not interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists, because the constitution forbids it, and the general welfare does not require us to do so. We must not withhold an efficient fugitive slave law because the constitution requires us, as I understand it, not to withhold such a law. But we must prevent the outspreading of the institution, because neither the constitution nor general welfare requires us to extent it. We must prevent the revival of the African slave trade and the enacting by Congress of a territorial slave code. We must prevent each of these things being done by either Congresses or courts. The people of these United States are the rightful masters of both Congresses and courts not to overthrow the constitution, but to overthrow the men who pervert that constitution.

"To do these things we must employ instrumentalities. We must hold conventions; we must adopt platforms if we conform to ordinary custom; we must nominate candidates, and we must carry elections. In all these things, I think that we ought to keep in view our real purpose, and in none do anything that stands adverse to our purpose. If we shall adopt a platform that fails to recognize or express our purpose, or elect a man that declares himself inimical to our purpose, we not only take nothing by our success,

but we tacitly admit that we act upon no [other] principle than a desire to have 'the loaves and fishes', by which, in the end our apparent success is really an injury to us."1

So patiently he explained to the audience how Douglas was resorting to falsehood to convince the public about his Doctrine of Popular Sovereignty. So diligently he explained the history of the arrival of states into the Union and the laws adopted by the Federal Government to safeguard the country against the spread of slavery. And so lucidly he educated the masses about the difference between hired labour and slaves. He wanted to prepare them to vote wisely during the next presidential elections.

Jesse Fell, a friend of Lincoln, who had encouraged him to enter into these debates with Douglas, had begun to find in him the potential for higher office. He urged Lincoln to consider running for the office of president of the United States. In his inimitable humility and candidness, he replied:

""Oh, Fell, what's the use of talking of me for the presidency, whilst we have such men as Seward, Chase and others, who are so much better known to the people... nobody, scarcely, outside of Illinois, knows me... I... admit that I am ambitious, and would like to be President... but there is no such good luck in store for me as the presidency of these United States; besides, there is nothing in my early history that would interest you or anybody else..."2"

In fact urged by him he wrote a short autobiography for Fell, who got it published in a newspaper on February 1860. In the attached letter he remarked, "There is not much of it, for the reason,

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, (1859-1865), Speech at Cincinnati, Ohio, 17th September 1859, p. 59

- http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/34129

I suppose, that there is not much of me."1

In December 1859 Lincoln visited various towns in Kansas and addressed large gatherings of people eager to listen to his charming speeches and reassuring words. People responded with thundering applause.

On the evening of February 27, 1860 Lincoln addressed a large and brilliant audience at the Cooper Institute. An eyewitness that evening recounted:

"'When Lincoln rose to speak, I was greatly disappointed. He was tall, tall, — oh, how tall, and so angular and awkward that I had, for an instant, a feeling of pity for so ungainly a man... As Lincoln warmed to his subject, however, a change came over him. He straightened up... his face lighted up as with an inward fire; the whole man was transfigured. I forgot his clothes, his personal appearance, and his individual peculiarities. Presently, forgetting myself, I was on my feet like the rest, yelling like a wild Indian, cheering this wonderful man... When he reached a climax, the thunders of applause were terrific... When I came out of the hall, my face glowing with excitement and my frame all a-quiver, a friend, with his eyes aglow, asked me what I thought of Abe Lincoln, the rail-splitter. I said, `He's the greatest man since St. Paul."'2

During their debate at Ohio, Stephen Douglas had tried to convince the public that the Founding Fathers had believed in the system of slavery. To refute that statement, Lincoln prepared his speech after carefully examining the views of the 39 signers of the American constitution. He found that 21 of them believed that slavery should not be allowed to expand. In his speech he gave a detailed analysis along with statistical data of the views of the Founding Fathers individually, thereby proving to the

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings, (1859-1865), To Jesse W. Fell, Enclosing Autobiography, Dec. 20, 1859, p. 106

The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace, by H.W. Brands

audience that the position taken by the Republicans was not revolutionary, but similar to that of the Founding Fathers. He captivated the audience with his powerful words, and made direct and sharp references to the escalating discontent and aggression in the Southerners and their threat to secede if a Republican was elected President:

"...And how much would it avail you, if you could... break up the Republican organization? Human action can be modified to some extent, but human nature cannot be changed. There is a judgment and a feeling against slavery in this nation, which cast at least a million and a half of votes. You cannot destroy that judgment and feeling —that sentiment — by breaking up the political organization, which rallies around it..."

He advised his fellow Republicans of the need to be temperate but fearless in doing what they believed to be right:

"...A few words now to Republicans... Even though much provoked, let us do nothing through passion and ill temper... If slavery is right, all words, acts, laws, and constitutions against it, are themselves wrong, and should be silenced, and swept away... but, thinking it wrong, as we do, can we yield to them? Can we cast our votes with their view, and against our own? In view of our moral, social, and political responsibilities, can we do this?

"...Wrong as we think slavery is, we can yet afford to let it alone where it is... but can we, while our votes will prevent it, allow it to spread into the National Territories, and to overrun us here in these free States? If our sense of duty forbids this, then let us stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively... Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government... Let us have

faith that right makes might; and in that faith, let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it."1

His speech was published extensively in newspapers and used as campaign literature. It electrified intelligent and well-read New York citizens and Lincoln gained support in what was the home territory of William Seward, a Republican presidential nominee. It made him a known and popular figure throughout the country and was very much instrumental in his nomination for the Presidency. The press praised his speech and published rave reviews in their newspapers.

His successful address at Cooper Union institute had bolstered his confidence about his nomination for presidential elections on the Republican ticket. He toured New England for two weeks addressing folk and helping Republican candidates. Till now he had been a bit doubtful whether he would be nominated; but after his successful eastern tour and its thunderous response from the public, he confessed to Trumball2, 'The taste is in my mouth a little.'3

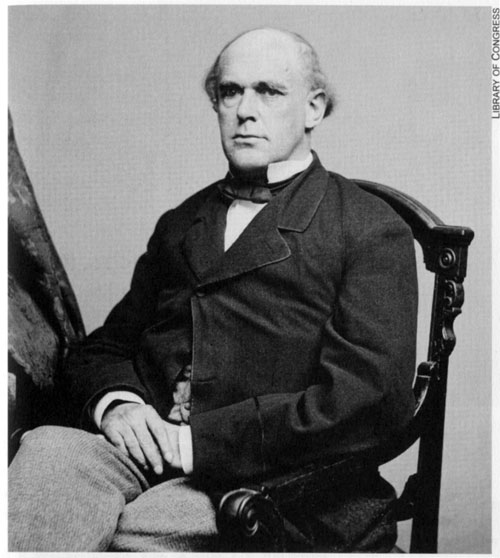

In May 1860, the Illinois state convention of the Republican Party met to choose their Presidential candidate. There were four main contenders for the office of the president — William Seward from New York was considered the front runner; with Lincoln of Illinois, Salmon Chase of Ohio and Edward Bates of Missouri behind him. Seward was an experienced statesman and politician, a known leader in the Republican Party, having served as New York's governor earlier and currently a senator. Lincoln, on the other hand, was just a country lawyer, having come into limelight only as the competitor of Senator Douglas in Illinois in 1858. His political reputation and support came mainly from the west. Therefore, Seward's supporters expected their nominee

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Cooper Union Speech, p. 111

- Lyman Trumbull was a United States Senator from Illinois during the American Civil War, and co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), To Lyman Trumbull, April 29, 1860, p. 154

would, without doubt, be nominated. Yet Lincoln's Cooper Institute speech, had made him popular in the east, and 'honest old Abe' now became a known figure in most of the free states.

Despite his lack of experience and polish, Lincoln won the nomination and was declared the Republican Party's presidential candidate with Senator Hannibal Hamlin as his vice-presidential running mate. Their platform stated the following: containment of slavery, abolishment of popular sovereignty, freeing of Kansas, high tariffs, internal improvements, and development of frontier regions — issues very close to Lincoln's heart.

There is a wonderful anecdote with regard to his nomination:

"Judge Kelly of Pennsylvania, one of the committee, and a very tall man, looked at Mr. Lincoln, up and down... a scrutiny that had not escaped Mr. Lincoln's quick eye. So, when he took the hand of the Judge, he inquired: "what is your height?" "Six feet three," replied the Judge. "What is yours, Mr. Lincoln?" "Six feet four," responded Mr. Lincoln. "Then, sir," said the Judge, "Pennsylvania bows to Illinois. My dear man," he continued, "for years my heart has been aching for a president that I could look up to; and I've found him at last, in the land where we thought there were none but little giantsi.1'2

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party split due to irreconcilable differences on the principle of slavery. Eventually, there was Lincoln of the Republicans, Stephen Douglas of the Democrats, John Breckenridge of the Southern Democrats and a third party sprang up called the Constitutional Union Party with their presidential candidate, John Bell.

Lincoln did not do any active campaigning; in fact he did not leave his hometown. He urged his visitors at Springfield to read his earlier speeches. In contrast, Douglas and Southern Democratic

- 'little giants' is a reference to Stephen Douglas

- Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J.G. Holland, p. 230

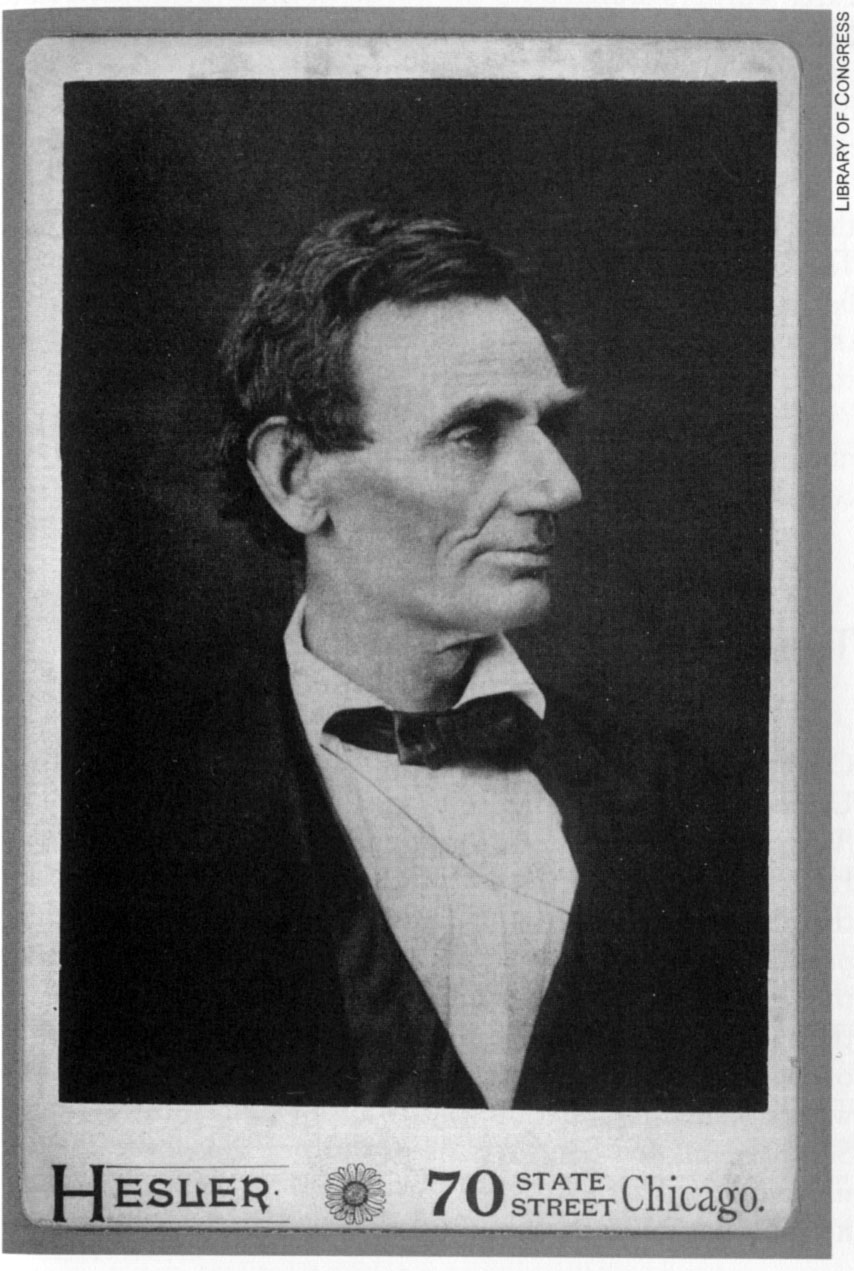

Candidate for US President (1860)

Party workers toured both the northern and the southern states. Lincoln's party workers campaigned zealously, focusing on their party's platform and thoroughly utilizing his life sketch — his humble rural background, his native intelligence, his rise from obscurity to prominence.

The Republicans were confident of Lincoln's win provided they could establish their popularity in the northern states. They did not even campaign in the southern states but for a few border cities. By the end of the campaigning it was evident that the republicans had a clear advantage in the north. Its interesting to note that because of their system of counting, Lincoln won a sweeping 180 of a total of 303 electoral votes; 152 being the number needed to win, even though he won less than forty percent of the popular vote.1 (see Map p. XIV, A & B)

To The White House, Mr. President

On 6th November 1860, Lincoln was elected president of the United States. His response to his friends and supporters was, `Well, boys, your troubles are over now, but mine have just begun.'2 He was referring to the threat given by some Southern states that they would secede if an 'anti-slavery' republican was elected president. Though republicans had declared that they supported the right of each state to choose to be pro slavery or anti slavery their party platform stated that they were against the expansion of slavery in new territories. Having a national government, which wished to arrest the expansion of slavery, threatened the Southerners. Ten Southern states did not even have Lincoln's name on the ballot. It was a formidable task before him, — to keep his nation from falling apart.

- Presidential Elections in the USA, Appendix III

- Conversations with Lincoln, Compiled, edited and annotated by Charles M. Segal, p. 38

Till now the federal government had placated the south through legislations to arrest the spread of slavery but never attempted to put an end to it. But with the coming of Lincoln as President of the United States of America the southern states were convinced that the days of placation would soon be over.

No sooner had the news of his victory at the polls been announced, (See Chart p. XIV) he was beset with throngs of people who wished to meet with him — 'those who called for love and those who sought for office'1 Many advised him on the choice for his cabinet members; some republicans wished to make peace with the south by installing Southerners into it and compromising on the issue of slavery. But that was not acceptable to Lincoln; he would not compromise on his principles and though he knew that the road ahead was dark and dangerous he kept firm in his beliefs and refused such advice.

"All that I am in the world — the Presidency and all else

— I owe to the opinion of me which the people express when they call me 'Honest Old Abe'. Now, what would they think of their honest Abe if he should make such an appointment as the one proposed?"2

`Harboring no jealousies, entertaining no fears concerning his personal interests in the future, he called around him the most powerful of his late rivals — Seward, Chase, Bates — and unhesitatingly gave into their hands powers which most Presidents would have shrunk from committing to their equals, and much more to their superiors, in the conduct of public affairs.'3 Despite the fact that they thought themselves to be superior to him in their education, social standing and their tenure in politics, Lincoln had made up his mind about having them in his cabinet. Lincoln knew that they would be capable of steering the country through this civil turbulence.

- Holland's Life of Abraham Lincoln, J.G. Holland, p. 233

- The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Francis Fisher Browne, p. 257

- Ibid., p. 257

Seward gradually came to admire Lincoln and became his closest friend among his secretaries. Edward Bates was selected as an appeasement to the Border States that were proslavery. Chase, though highly egoistic and ambitious, was chosen as Secretary. of Treasury because of his astute mind. Simon Cameron, extremely corrupt and greedy was the only person in his cabinet, who was given an office as a favour. Edwin Stanton who replaced Cameron was critical of Lincoln at first, but grew to admire and respect him and became one of his most faithful secretaries. Once when someone commented that Stanton had made an uncomplimentary remark about him, Lincoln brushed it aside, `If Stanton said that I was a damned fool, then I must be one, for he is nearly always right, and generally says what he means. I will step over and see him.'1 His lack of vanity was his very strength that with his straightforwardness and humility kept his warring cabinet together.

His victory at the polls did not go well with the southern states. South Carolina seceded from the union the very next month in December 1860. President Buchanan did not take any military action against this rebellious act; not willing to distance either one, he declared on one hand that the Southern states had no legal right to secede and on the other that the Federal Government had no legal right to prevent them from seceding.

Efforts were made by various sections of society to prevent this schism. Lincoln began to arrest the tide of slavery even before he assumed office. He privately communicated to various republicans in Congress advising them:

"Entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The instant you do, they have us under again; all our labor is lost, and sooner or later must be done over. Douglas is sure to be again trying to bring in his Top. Soy.' Have none of it. The tug has to come &

1. Walking with Lincoln: Spiritual Strength from America's Favorite President, by Thomas Freiling

Two of Lincoln's rivals who eventually became his indispensable Cabinet Secretaries

William Seward, Lincoln's Republican rival for the presidential nominations of the 1860 elections.

Edwin Stanton, a Democrat and a prominent lawyer. Though he had slighted Lincoln during a court case and was overbearing and ill tempered, Lincoln selected him for his innate honesty and intelligence.

better now than later.

You know I think the fugitive slave clause of the constitution ought to be enforced-to put it on the mildest form, ought not to be resisted."1

Meanwhile, events were moving towards a face off between South Carolina and the White House. Refusing to accept the demands of South Carolina to evacuate Charleston Harbour, Buchanan sent a supply ship to fortify Fort Sumter. Spotting it as it approached the harbour, South Carolina opened fire on it, forcing it to retreat.

Emboldened by South Carolina's aggression, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana followed suit and seceded from the Union with Texas being the last of the seven Southern states to do so on 1st February 1861. The rebel states met and formed the Confederate States of America under the presidency of Jefferson Davis and formed the Confederate army.

That was not all; every department in Washington was replete with spies and traitors; the Southerners in the Buchanan Cabinet and in Congress set into motion their plans to pillage the government of its resources. The federal treasury was depleted, navy ships were dispersed from their posts and arsenals were plundered to equip the southern army. Simultaneously, the Confederates seized several Southern coastal forts and war supplies.

All this he saw from a distance, knowing well that with seven rebellious states on his hands the Presidency would bring with it a crown of thorns. He was kept informed by fellow republicans in Congress about all important turn of events. The Border States were a buffer between the South and Washington; if they seceded, Washington would be vulnerable and its capture a calamity. General Scott had warned President Buchanan about the need to fortify their position in the Southern forts against the

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), To William Kellogg, Dec. 11th 1860, p. 190

aggression from the seceded states; Buchanan ignored his advice; Lincoln, through a fellow republican, however, requested of General Scott, `...to be as well prepared as he can to either hold or retake the forts, as the case may require, at and after the inauguration.'1

Before departing for Washington, Lincoln decided to bid farewell to his stepmother. He travelled to Coles County and spent a day with her, reminiscing about his childhood and her cheerful influence on him. It was a sentimental reunion; she was worried for his safety and as he hugged her he had tears in his eyes.

A day prior to his departure from Springfield, Lincoln came to the law office to complete some unsettled matters with Herndon who relates a touching anecdote. After all the work was over, he `threw himself down on the old office sofa... He lay for some moments, his face towards the ceiling... Presently, he enquired, Billy... how long have we been together?" "Over sixteen years," I answered. "We've never had a cross word during all that time, have we?" To which I returned a vehement, "No, indeed we have not". He then recalled some incidents of his early practice and took great pleasure in delineating the ludicrous features of many a lawsuit on the circuit... I never saw him in a more cheerful mood... Before leaving he made the strange request that the signboard which swung on its rusty hinges at the foot of the stairway should remain. "Let it hang there undisturbed", he said, with a significant lowering of his voice. "Give our clients to understand that the election of a President makes no change in the firm of Lincoln and Herndon. If I live I'm coming back some time, and then we'll go right on practicing law as if nothing had ever happened." He lingered for a moment as if to take a last look at the old quarters, and then passed through the door into the narrow hallway.2

On his departure from Springfield on 11th February 1861, his farewell address reflects the gravity of the state of affairs the

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 4, letter to E.B. Washburne, Dec. 21st 1860, p. 159

- Herndon's Life of Abraham Lincoln, William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, pp. 389-90.

nation was in. His faith and belief in God are evident in his appeal to the people of Springfield.

"... I go to assume a task more difficult than that which devolved upon General Washington. Unless the great God who assisted him, shall be with and aid me, I must fail. But if the same omniscient mind, and Almighty arm that directed and protected him, shall guide and support me, I shall not fail, I shall succeed. Let us all pray that the God of our fathers may not forsake us now... Friends, one and all, I must now bid you an affectionate farewell."1

All his speeches on the way to Washington were well thought out, temperate, and yet with a sincere heartfelt honesty, asking his people for patience and faith in the American constitution. But, there was also a quiet resolve and firmness with regard to the problem of secession.

"I shall endeavor to take the ground I deem most just to the North, the East, the West, the South, and the whole country. I take it, I hope, in good temper — certainly no malice toward any section. I shall do all that may be in my power to promote a peaceful settlement of all our difficulties. The man does not live who is more devoted to peace than I am. None who would do more to preserve it. But it may be necessary to put the foot down firmly."2

Along with temperance and warmth, his speeches contained words of eternal wisdom:

"...If the politicians and leaders of parties were as true as the PEOPLE, there would be little fear that the peace of

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln,volume 4, Farewell Address at Springfield, Illinois, Feb 11, 1861, p. 190

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Address to the New Jersey General Assembly at Trenton, NJ, Feb. 21, 1861, p. 210

the country would be disturbed. I have been selected to fill an important office for a brief period, and am now, in your eyes, invested with an influence which will soon pass away; but should my administration prove to be a very wicked one, or what is more probable, a very foolish one, if you, the PEOPLE, are but true to yourselves and to the Constitution, there is but little harm I can do, thank God!"1

An assassination plot was uncovered which forced him to travel in the cover of darkness. Travel schedules were changed to foil the assassination attempts. Lincoln was forced to enter Washington quietly under guard of General Scott's men — a fact that was used by his adversaries to mock him as a coward. But prior to that, against the advice of his friends and colleagues he insisted on keeping to his schedule of raising the flag in Philadelphia, 'even if it cost him his life.'

After twelve days of chequered journeying, dodging assassination plots and giving speeches in various towns and cities, he arrived in Washington.

He was not met with a warm welcome there, — its high society was against him and his principles. But despite the antagonistic atmosphere and threats of assassination looming on him, on 4th March 1861, after a strong inaugural address, assuring the people that he did not wish to deprive the South of their constitutional rights with regard to slavery, reasserting the rights of both state and federal governments but keeping the overall stress on the dire need of preserving the union, and remarking the secession by the Southern states legally null and void, he took oath of office and became the 16th president of the United States of America:

"Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories,

1. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 4, p. 197

and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain precisely why we do it?

"... In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. 'You' have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to preserve, protect, and defend it."1

With great finesse he put the onus of any aggression on the South and any war by the union as a rightful defense to protect the nation, thereby fulfilling his declaration that he only wanted to preserve the nation.

"I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."2

He ended on a conciliatory note appealing to the people of the south to remember that they were brothers belonging to the same nation.

However, contrary to his appeals and hopes, the very next day, word reached Washington that Fort Sumter had been surrounded by the confederacy and was running out of supplies.

If supplies were sent, the confederacy would attack. Without supplies General Anderson would be unable to hold the Fort.

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), First inaugural address March 4th 1861, p. 215

- Ibid., p. 215

Having declared that the union would not be the aggressor, Lincoln could not send reinforcements, as it would be called an act of war. Fearing loss of men and resources, Seward, Secretary of State and General Scott advised him to abandon the fort but Lincoln was loathe to do so, 'by many it would be construed as a part of a voluntary policy; that at home it would discourage the friends of the Union, embolden its adversaries... in fact, it would be our national destruction consummated.''1 After much deliberation with other seasoned politicians, Lincoln sent a messenger with a note to the Governor of South Carolina:

"...I am directed by the President of the United States to notify you to expect an attempt will be made to supply Fort-Sumter with provisions only; and that, if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition, will be made..."2

This notice seemed premonitory — even before the relief ship could arrive at Charleston Harbour, the Confederates demanded the evacuation of Fort Sumter. On Major Anderson's refusal, they opened fire on Fort Sumter. Outnumbered in men and ammunition, on 14th April, the union army surrendered. The Civil War had begun (see Map p. XV). -

While the revolution almost a hundred years ago against the mother country Britain, had created the United States, the Civil War between brothers would decide whether it was to be an undivided nation with a sovereign national government or a loose federation of independent states. On this outcome would rest its destiny — whether it would break into small quarreling countries where slavery still existed in some of its parts or it lived up to its declaration that all men were created equal.

Lincoln was neither in favour of war nor of keeping peace. He only wished to preserve the union and with this aggressive

- Ibid., Special Message to Congress 4th July 1861, p. 246

- Ibid., letter to Robert S. Chew, April 6th 1861, p. 229

act of the Confederates, he felt that war would put an end to this rebellion. Having informed South Carolina that the relief ship would only be carrying provisions, the Union was now justified in protecting itself 'in self defense'.

The very next day, on the 15th of April, he issued a proclamation to the state governors calling for 75000 troops. And on the 19th of April, Lincoln issued a proclamation declaring a blockade of the ports of South Carolina, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia and Alabama. Not having much industry, the south depended on foreign supplies for weapons and other goods. They traded cotton for weapons with England. To prevent goods, troops and weapons from entering the southern states, the Union Navy used as many as 500 ships to patrol the east coast from Virginia to Florida and the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas. With these two key steps Lincoln commenced armed hostilities against the South in an attempt to preserve the union.

Virginia responded to the call for military volunteers by joining the confederacy, followed soon by Tennessee, North Carolina and Arkansas. Young men from both sides North and South joined their armies to fight for what they believed in. Those in the South did so, not so much for the cause of slavery but because they believed that a state had a right to self-rule.

To counter the effect of Virginia's defection, in April, Lincoln offered the command of the Union armies to Colonel Robert E. Lee, noted for the capture of John Brown, an abolitionist who began an armed rebellion to put an end to slavery. Although Lee was against slavery, his allegiance to his home state prompted him to decline the offer, resign from his military position in the union army and join the confederacy. With great foreboding he remarked, 'there is a terrible war coming, and these young men who have never seen war cannot wait for it to happen, but I tell you, I wish I owned every slave in the South, for I would free them all to avoid war.'1

1. Building Fluency Through Practice and Performance: American History, by Timothy Rasinski, Lorraine Griffith, p. 69

Salmon Chase, another rival during the republican nominations for the elections of 1860

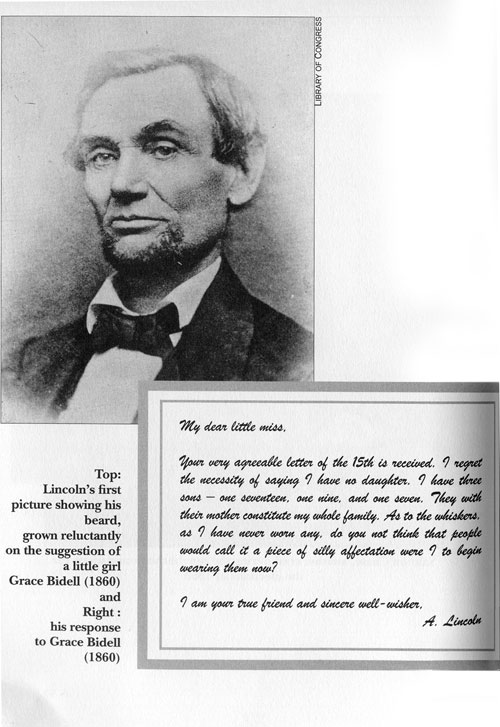

Top: Lincoln's first picture showing his beard, grown reluctantly on the suggestion of a little girl Grace Bidell (1860) and Right : his resonse to Grace Bidell (1860).

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet