Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist - The Story of Abraham Lincoln - Chapter V

|

Chapter V

Welcome Again,

"Long Abraham Licoln a Little Longer" November 1864. |

On 8th November, 'Uncle Abe' was reelected president of the United States of America; he won by a margin of more than 500,000 votes. The results were over-whelming, — but for New Jersey, Delaware and Kentucky, every state had voted for the Republican Party. McClellan received 45% of the popular vote, mostly from Irish and German American voters. Soldier votes went largely to 'Father Abraham', despite the fact that McClellan was a popular commander. The voters of 1860 had not changed their allegiance; countryside farmers, skilled workers, city professionals and the youth all voted for the Republican Party.

Apart from feeling relieved at his victory, Lincoln felt great happiness to see 'that a people's government can sustain a national election, in the midst of a great civil war1; four million people had stepped out to vote. Despite his overwhelming victory, hoping to unite and work towards a common goal for the good of their nation he appealed to the Democrats, ' ...now that the election is over, may not all, having a common interest, re-unite in a common effort, to save our common country?'2

Assassination attempts had been on him made prior to his inauguration in 1861. By now threat letters ceased to disturb him; he refused to see them and asked his secretaries to throw them away. He believed that if conspirators plotted his death, no policing could prevent them from doing so. But with his reelection, confederates and their North sympathisers felt bitter about having to put up with his government for another term. Stanton and others in the administration worried about his safety; they deployed armed personnel to escort him when he went out and also stationed them outside his private rooms in the White House. A kidnapping attempt had failed in September 1864; he had also escaped a shot fired at him during his ride home from Soldier's Home. He knew he was in danger but he was

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Response to a Serenade November 10, 1864, page 641

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Response to a Serenade November 10, 1864, page 641

determined not to worry about it. On the night of November 8th, after the election results came in, Ward Lamon, Lincoln's friend and bodyguard, armed with weapons to protect the president, slept outside Lincoln's bedroom door through the night.

Before his inauguration in March, Lincoln had selected some new members for his cabinet, — Seward, Stanton and Welles he retained; they were invaluable to the tasks still pending. His new cabinet was a good blend of Radical and Conservative faction of the Republican Party. Compared to his previous cabinet members, who at the start were extremely ambitious and antagonistic towards each other and condescending towards him, his new cabinet members were genuinely fond of him. Stanton had become very close and attached to Lincoln. The years had softened Seward too towards Lincoln; he had grown to understand and appreciate the president for his qualities of both the head and heart.

Lincoln was straightforward yet tactful, could motivate and delegate, yet was decisive when needed, knew how to listen and also knew how to command, his humility, openness, lack of vanity and gratefulness; all these qualities produced the man and politician who not only managed his cabinet of rivals but also kindled in their hearts deep affection for him.

Not only his cabinet, his dealings with his generals were equally tactful and honest. Unhappy with two promotions given by the president to two of his officers, General Sherman telegraphed Washington about his displeasure. Instead of getting annoyed, Lincoln responded, 'the two appointments referred to by you... were made at the suggestion of two men whose advice and character I prize most highly. I refer to Generals Grant and Sherman.'1

It was also time to decide on the Chief Justice of the nation. Lincoln knew that most cases in the coming years would involve the constitutionality of his policies regarding liberation of slaves and the legality of paper money that the Treasury printed to

1. Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Allen Thorndike Rice, p. 27

finance the war. Lincoln knew that Chase was a capable man; he had been responsible for the implementation of the National Banking Act in 1863, which provided a unified banking system to the country, the issue of paper currency 'greenbacks' in various denominations as well as the establishment of the Bureau of Internal Revenue for the collection of taxes in an effort to finance the war. Ignoring his reprehensible behavior towards him, Lincoln decided on Chase as Chief Justice; he knew he was the right man for the job.

Thirteenth Amendment

The new session of Congress beginning 5th December began uneventfully; with his overwhelming victory and the military successes, it was difficult for the opposition to attack him. In his annual message to Congress on December 6th 1864, he requested the members of the House to support the thirteenth amendment to the constitution abolishing slavery. In the previous Congress the Senate had passed the bill but it did not get the two-third majority in the House of Representatives. Lincoln had got it included as the keystone in the party platform of the National Union Convention. He added that:

"The intervening election shows almost certainly that the next Congress will pass the measure if this does not. Hence there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amend-ment will go to the States for their action. And as it is to so go at all events, may we not agree that the sooner the better?"'

Having made his appeal to congressmen, he now got to work

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Annual Message to Congress, p. 658

to ensure the passage of this bill in the House; on it rested the abolition of slavery from the country, and the consequent end of the rebellion. He went into collaboration with James M. Ashley, who had introduced it in Congress in 1863.

Another development was taking place simultaneously; three confederate Government representatives were making their way towards City Point to negotiate for peace; this time it was not a plot by the Democrats or the confederates.

Earlier, Lincoln was against all peace talks with the confederates; therefore he had insisted on abolition of slavery as the condition knowing it would not be acceptable; also there was the risk that peace talks would lead to a truce that would give the confederacy its independence.

However, circumstances had changed. The Southern spirit to fight had been weakened by Sherman’s and Thomas’ victories in the West and Grant’s unrelenting siege on Petersburg in the East. The confederacy was almost ready to fall apart. Governors of Georgia and North Carolina were planning to make peace independent of the confederate government. A peace commission created by the Confederate House of Representatives had turned hostile towards Jefferson Davis, blaming him for the continuation of the war. This seemed like an opportune moment to strike. Towards the end of his annual message, Lincoln advised the public:

“…no attempt at negotiation with the insurgent leader could result in any good. He would accept nothing short of severance of the Union — precisely what we will not and cannot give…”

Alluding to Georgia and North Carolina, he said:

“…What is true, however, of him who heads the insurgent cause, is not necessarily true of those who follow. Although he cannot reaccept the Union, they can. Some of them, we know, already desire peace and reunion. The

number of such may increase. They can, at any moment, have peace simply by laying down their arms and submitting to the national authority under the Constitution…”1

With that several emissaries from the North went forth to meet with the governors of those Southern states, which had openly shown an inclination to make peace. Most failed, but Francis Blair came back from Richmond carrying a letter from Davis, promising to appoint representatives for negotiating peace between the ‘two countries’. Not wanting to acknowledge the confederacy as a separate country, Lincoln sent Blair back with a message for Davis stating that he looked forward to ‘se-curing peace to the people of our one common country’.

To avoid endangering the passage of the thirteenth amendment, Lincoln diverted the three confederate representatives to City Point, Virginia instead of receiving them in Washington.

However, during the last few days of the debate in the house, word did get around. Frantically, Ashley inquired from Lincoln, ‘The report is in circulation in the House that Peace Commissioners are on their way or are in the city, and is being used against us. If it is true, I fear we shall loose the bill. Please authorize me to contradict it, if not true.’2

In response, Lincoln carefully penned the following on the same letter, ‘So far as I know, there are no peace commissioners in the city, or likely to be in it.’3

Some Congressmen were coaxed and some were pressurized while Seward bribed some with political appointments into supporting the bill. On 31st January 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment came through, voted for by more than two thirds of the house and sent to the states for ratification. Thaddeus Steven, who had worked on the antislavery movement for decades, aided Seward and Lincoln in pushing it through. ‘The

_________________________

-

Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Annual Message to Congress, p. 658

-

Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 8, letter from James Ashley, Jan. 31. 1865, p. 248,

-

Ibid., p. 248

greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America,’1 he said.

Thrilled with this landmark event; Lincoln could rest assured that the nation now had the ‘King’s cure for all evil’2 to abolish slavery utterly and completely and with it, put an end to the war.

By end December Lincoln had received news of two new victories — Sherman had terminated his march to the sea by taking the city of Savannah and Thomas had checked the confederate invasion of Tennessee and destroyed their army at Nashville. The Thirteenth Amendment had been secured; fortified, he now turned his attention to the matter he had put on hold, — the confederate commissioners waiting at City Point for peace negotiations.

On 3rd February, he met them with Seward on the ‘River Queen’, his steamer at Hampton Roads. He rejected the confederate offer of truce to jointly fight the French out of Mexico. He offered them restoration of the Southern states into the union provided they laid down their arms in submission to the United States of America. Seward also announced that the Thirteenth Amendment of the constitution had been passed by the House and had been sent to the states for ratification. Seeing them unnerved Lincoln offered to them a word of advice. ‘Were I in your place, he said, ‘I would ‘get the governor of the state (Georgia) to call the legislature together, and get them to recall all the State troops from the war; elect Senators and Members to Congress, and ratify this Constitutional Amendment prospectively, so as to take effect

— say in five years…’3 Completely disturbed, the confederate commissioners returned to Richmond from peace negotiations that were an absolute failure.

____________________________

- Our Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln, John Brown, and the Civil War Era, by Stephen B. Oates, p. 83

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Response to a Serenade, February 1, 1865, p. 670

- The Collapse of the Confederacy, edited by Mark Grimsley, Brooks D. Simpson, p. 32

With Charity to All

These had been busy months; with great difficulty the Thirteenth Amendment had gotten through; the war, though now steering favourably in their direction, was still going on. His kind heart found it most disturbing when he had to review court martial cases. He pardoned soldiers who had been sentenced to death for sleeping on sentry duty, desertion and even treason; he was ‘unwilling for any boy under 18 to be shot’. ‘If almighty God gives a man a cowardly pair of legs, how can he help their running away with him?’1 he asked. And yet, when Nathaniel Gordon, who was convicted for capturing 800 negroes for selling them as slaves, appealed for pardon, Lincoln refused, ‘I believe I am kindly enough in nature, and can be moved to pity and to pardon the perpetrator of almost the worst crime that the mind of man can conceive… but any man, who, for paltry gain and stimulated only by avarice, can rob Africa of her children to sell into interminable bondage, I never will pardon.’2

Gideon Welles and Edward Bates, members of his cabinet criticized his kindness; it obstructed the course of military procedure, they felt. They often told him that ‘he was unfit to be entrusted with the pardoning power’.3 When two women came to him with a plea to pardon family members who had been imprisoned for resisting the draft, he called General Dana and after verifying the matter he instructed, ‘these fellows have suffered long enough… and now that my mind is on the subject I believe I will turn out the whole flock…’ The older woman, with tears in her eyes, said, ‘I shall probably never see you again till we meet in heaven.’ Taking both her hands in his, he replied, ‘I am afraid with all my troubles I shall never get to the resting place you speak of… that you wish me to get there is, I believe, the best wish you

_______________________

- Presidential Anecdotes, by Paul F. Boller, page 139

- The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, by Michael Burlingame, p. 23

- The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln, by Carpenter, pp. 68-9

could make for me…’ Worried about serious matters that affected the destiny of the nation, Lincoln was just as sensitive about the destiny of individuals. He confided to his friend, Joshua Speed who witnessed this meeting, ‘Die when I may, I want it said of me by those who know me best to say that I always plucked a thistle and planted a flower where I thought a flower would grow.’1

Lincoln’s compassion was directed towards all; even his enemy. During his visit to an army hospital, he asked a confederate soldier whose leg had just been amputated, ‘Would you shake hands with me if I were to tell you who I am?’ When the confederate said yes, Mr. Lincoln told him, ‘I am Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States.’ The eyes of both men filled with tears’2.

In fact, Lincoln’s compassion was endless; he saved hundreds of ‘sleeping sentries from the firing squad, reunited miscreant husbands with tearful wives and restored last-surviving sons to their widowed mothers’3.

With the winds of change that altered circumstances, Lincoln was quick to change his course of action. Earlier, the need of the hour was the abolition of slavery. Now with the Thirteenth Amendment signed and delivered, abolition was assured and ceased to be a pressing need. The need of the hour currently was to end the war and restore the Southern states back into the union, even if it happened piecemeal, state by state. In fact, he felt that if Southern states broke away from the confederacy and rejoined the union, it would end the rebellion. To accomplish that, he made a proposal to Congress stating that $400,000,000 were to be arranged for disbursement to the Southern states as compensated emancipation for their slave population. Lincoln was sincerely devoted to the cause of restoration of the union and the liberation of slaves — and was willing to be as generous as possible to achieve both his objectives. The republicans supported him fully in the creation of the Bureau of Freedmen,

_______________________________

- Herndon’s Life of Lincoln, by William H. Herndon, Jesse W. Weik, p. 424

- Conversations with Lincoln, Charles M. Segal, editor, p. 210

- Civil War News, Book review by Dr. Allen C. Guelzo of ‘Don’t Shoot That Boy! Abraham Lincoln and Military Justice’, by Thomas P. Lowry

Abandoned Lands and Refugees; these offices would oversee the transition from slavery to freedom in the Southern states.

In view of the favourable circumstances of war and mandate, Lincoln firmly declared that he would veto any reconstruction bill that did not recognize the free state government that had been set up under his 10% plan in Louisiana. Apart from their importance for the restoration of the union, these free state governments were necessary for the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, which needed the votes of at least 27 of the 36 states before it could go into effect. Counting all Northern states and Border States where slavery had been abolished by now, they fell short of two votes. These votes could only come from those confederate states that were now under federal control. And without a government the amendment could not be ratified. To appease the radicals, Lincoln accepted Negro suffrage; his own thinking had evolved and he now believed that the educated African Americans and those who had served in the army should be permitted to vote. He showed them a copy of his letter to Governor Hahn, suggesting limited enfranchisement of blacks. Lincoln was in a hurry; he came straight to the point and asked the Senate, ‘Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relations with the Union, sooner, by admitting or by rejecting the proposed Senators?’1 With great difficulty the Senate managed to get a majority of the Republicans to support the Louisiana bill, but because Negro enfranchisement was absent from their constitution, Charles Sumner and his group of Radicals blocked it. Despite Lincoln’s resolve to keep the reins of control over reconstruction in his hands, he could not steer it towards a Congressional approval for the admission of Louisiana.

_______________

1. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. 8, To Lyman Trumbull, Jan 9, 1865, p. 207

Time To Rejoice

On March 4th, 1865, Lincoln was inaugurated a second time as America’s President. A huge crowd had collected on that cold and rainy day. Lincoln kept his speech short; he put forth before the people his thoughts about the war, a war that neither side thought would wreak so much devastation and pain to its people and yet needed to be fought till the end so that a ‘just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations’ could be established:

“On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war… And the war came…

“Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease…

“Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. ‘Woe unto the world because of offences! For it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!’ If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence

came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him?

“Fondly do we hope — fervently do we pray — that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the na-tion’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”1

With these words Lincoln closed his address to the people at his second inauguration. In just 700 words he summed up the cause of war without directly attributing blame for it. As though he were looking down from above, he saw the spectacle of war as two brothers wrestling with each other. His wideness of vision is clear in his introspection of the civil war; ‘All dreaded it — all sought to avert it’. The war and the destruction it had wreaked had compelled him more and more to look towards the heavens for Divine Guidance. Lincoln always held both north and south responsible for bringing slavery into the country. He bows before the omnipotence of God and while praying for the speedy end of ‘this mighty scourge’, with true surrender and faith he adds that the cessation or continuation of war was no more in the

_______________________

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), Second Inaugural Address, p. 294

hands of men, but in the hands of the Almighty. Inwardly, the sense of doer ship no more belonged to him. He had handed his instrumentality to the Divine.

Not all people understood his speech; it was not a standard speech speaking of war victories and promises. However, it pleased the radicals, the abolitionists and specially Frederick Douglass who called it a ‘sacred effort’. ‘I believe it is not immediately popular’, he wrote to Thurlow Weed, ‘Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world. It is a truth which I thought needed to be told…’1

On the night of the inaugural ball at the White House, when the police tried to stop Douglass from entering, Lincoln sent word to let him in — the first time that an African American had been a guest at a presidential reception. Lincoln had grown during his presidency; the war and its perilous course had chiseled his being; he did not shrink from difficult decisions; he had assumed unprecedented war powers, his only shelter being the Grace of the Almighty to whom he would time and again turn towards for guidance. His purity of purpose gave strength to his resolve.

Extremely fatigued in mind and spirit, Lincoln took a few days off from work. He had begun to look old beyond his years. Mary, fearing that he would not last his second term, urged him to arrange a lighter timetable. To get his mind off his work, she persuaded him to go see plays, especially Shakespeare, his favourite. Lincoln went often with either Mary or Tod or his secretaries or sometimes with a party of friends. These visits to the theatre or the opera were as much for the enjoyment as it was for the rest he could get.

Perhaps the best relaxation he found was in the carriage rides he took with Mary in the afternoons. He enjoyed their quiet

|

1. Lincoln: Speeches and writings (1858-1865), letter to T. Weed, March 15, 1865,

p. 689

conversations, reminiscing the past and looking towards the future. He spoke of a European vacation with Mary and their sons. The Lincoln family had suffered much during the course of his presidency; the loss of Willie and Robert’s enlistment had almost driven Mary to the brink.

Lincoln’s mind was always on the battlefield where his generals were pushing into enemy territory to rout them out. He was often overcome with fear that the overconfidence of his generals would bring about a reversal in their war fortunes and Lee would escape the siege of Petersburg, head for North Carolina for reinforcements and start a new battle. His generals also had a tendency to interfere with peace negotiations; recently, Lee had approached Grant to discuss the issues between the two hostile forces. Having seen the detrimental effect of Grant’s interference during the peace talks with Davis’ men,1 Lincoln categorically told him that the military should refrain from such matters as they were directly under the jurisdiction of the President.

Lincoln did not only want peace but also reconciliation. To discuss this matter further, he decided to visit Grant at City Point. Mary and Tad accompanied him on the River Queen. On 28th March 1865, Lincoln met with Sherman, Grant and Porter for a discussion regarding terms of surrender. He was afraid that the defeat of the confederate army would lead to anarchy and lawlessness among the disbanded soldiers. Not only suspension of hostility but reconciliation could prevent that. He wanted them to ‘get the deluded men of the rebel armies disarmed, and back to their homes’2; he wanted ‘no revenge, no harsh measures, but quite the contrary’3. ‘We want those people to return to their allegiance to the union and submit to the laws’.4

________________________

- In January 1865, to ensure that Lincoln met with the confederate representatives for peace talks, Grant persuaded the confederate commissioners to delete any reference to ‘two separate countries’ from their offer before sending it to Washington.

- Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure, by J. G. Randall, Richard Nelson Current, p. 351

- Ibid.

- Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald, p. 574

The union army was gaining more ground daily; waiting eagerly for confederate surrender, Lincoln returned to Washington on 8th April reading lines from Macbeth to his guests on the River Queen.

|

Union Statistics 2.9 million men served 1.5 million enlisted — 3 years duration 630,000 casualties 360,000 killed in action or died of disease Confederate Statistics 1.2 million men served 800,000 enslited — 3 years duration 340,000 casualties 250,000 killed in action or died of disease |

General Lee surrenders to General Grant at Appomattox

The War Is Over

On 9th April, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court house. Lincoln hugged Stanton in sheer joy and relief but knew that a ravaged south and freed blacks awaited his leadership; just as five years ago the joy of winning his first presidential election, had brought with it the enormous responsibility of steering the nation through its domestic crisis. 11th April was a day of great jubilation; people gathered around the White House in joy; bands played, fireworks burst in the sky, men and women cried to see the President. Lincoln addressed the people from the 2nd floor balcony.

It was not a regular speech applauding the victories of the union armies; his mind had already moved on to the problems

that often befall a nation suffering from the ravages of war. During his trip to Richmond, he had seen for himself the destruction inflicted by the war on the city, its burning buildings, abandoned streets, shut windows and drawn blinds of Southern homes, Union soldiers and sailors manning the city, and felt a deep-seated comprehension of the agony that the soldiers and civilians in the south were experiencing. He feared that Southern ‘society would be broken up; the disbanded armies would turn into robber bands and guerrillas’,1 which he must try to prevent.

He began his speech by expressing hope that the union victories would finally result in the speedy establishment of peace, but thenceforth it was devoted to the experiment being carried out for reconstruction in Louisiana. He reached out to his Northern people to make them understand the urgency of reconciliation with the people of the south; to partner them in the process of reconciliation, to confide in them of the difficulties in achieving it. He wanted them to rise above personal animosity and short-sightedness and look towards the holistic wellbeing of the entire nation.

He spoke of the unfortunate collision between the Executive and the Legislative branches of the government with regard to the process of reconstruction and about the criticism of his support of the new Government of Louisiana. He affirmed the power of Congress to decide upon the admission of the Louisiana government. He also confided in them of the shortcomings in the Louisiana constitution:

“The amount of constituency… would be more satisfactory to all, if it contained fifty, thirty, or even twenty thousand, instead of only about twelve thousand, as it does. It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man”.

____________________________

1. Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, compiled and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, p. 485

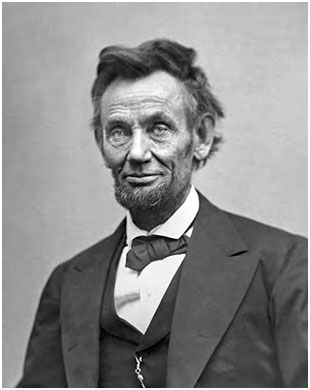

Lincoln in February 1865, two months before his death. The fatigue from pressures of office are clearly evident on his face.

He acknowledged his own personal desire to see the enfranchisement of the Negroes. He then spoke of all that it has accomplished:

“Some twelve thousand voters in the… slave-state of Louisiana have sworn allegiance to the Union… held elections, organized a State government, adopted a free-state constitution, giving the benefit of public schools equally to black and white, and empowering the Legislature to confer the elective franchise upon the colored man… Their Legislature has already voted to ratify the constitutional amendment recently passed by Congress, abolishing slavery throughout the nation.”

He appealed to the people to ‘join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper practical relations between these states and the Union’. He further warned them:

“If we reject, and spurn them, we do our utmost to disorganize and disperse them… If, on the contrary, we recognize, and sustain the new government of Louisiana… we encourage the hearts, and nerve the arms of the twelve thousand to adhere to their work… and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy, and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by saving the already advanced steps toward it, than by running backward over them?”

In the end he asked that though the Louisiana constitution is not all that is desired, ‘Will it be wiser to take it as it is, and help to improve it; or to reject, and disperse it?’1

______________________________

1. Lincoln, Speeches and writings (1858-1865), Speech on Reconstruction April 11, 1865, p. 697

He concluded that he would ‘make some new announcement to the people of the South’. It would seem that as he had allowed Campbell to assemble the rebel legislature of Virginia in order to withdraw from the confederacy, he might make the same offer to the other Southern states.

It was not a speech which the public was expecting, but it was an effort to ‘blaze a way through the swamp’ of criticism and opposition by the Radicals. It was an attempt to win their confidence and convince them of the effectiveness of this process of reconciliation and appeal for their support in his effort to put the war and devastation behind them as soon as possible.

There were those in the audience who sympathized with the south and felt that Lincoln had taken too many liberties. John Wilkes Booth was one of them. Hearing him speak of voting rights for blacks, he decided it would be the last speech he would ever make.

His 11th April speech unfortunately did not arouse the urgency that Lincoln aspired for. The Radicals did not accept his compromises for the Louisiana government. His own cabinet disapproved of his Campbell proposal for Virginia; consequently he sent word that since the confederates had surrendered, action on the part of the Virginia rebel legislature was not necessary.

Despite so much opposition, Lincoln did not give up. His cabinet met on the 14th April and agreed to restore and encourage commercial relations with the south. They all felt goodwill towards the Southern people and aspired to restore safety and government with as little harm to the people and their property. Even Lincoln acknowledged that he had ‘perhaps been too fast in his desires for early reconstruction’. Seeing their enthusiasm to find feasible reconstruction methods, Lincoln, feeling hopeful, observed that ‘if we were wise and discreet, we should reanimate the states and get their governments in successful operation, with order prevailing and the Union reestablished, before Congress came

together in December’.1 He knew that ‘men in Congress, if their motives were good, were nevertheless impracticable, and who possessed feelings of hate and vindictiveness in which he did not sympathise and could not participate’.2

The terms of surrender offered by Grant at Appomattox, pleased Lincoln; he was convinced that news from Sherman from North Carolina would be good; the previous night he had the same dream he always had before every significant victory: ‘he seemed to be in some singular, indescribable vessel, and… he was moving with great rapidity towards an indefinite shore.’3

During the last few years, pained by the ravages of war, he often remarked that he would not outlast the rebellion; ‘but in the flush of triumph, — in his large, loving, and liberal plans for the good of the people whom the fortunes of war had left at his feet, — in his dreams of the future Union and harmony of the states, — he forgot this, and was hopeful and happy’.4 That afternoon, he slipped away with Mary for a carriage ride. Even she found his cheerfulness delightful, to which he responded, ‘we must both be more cheerful in the future, between the war and the loss of our darling Willie, we have both been very miserable.’5

He Belongs To The Ages

He looked forward to going to the theatre that evening. Major Rathbone and his fiancée were to be his guests. His advisors begged him not to go; with the recent confederate surrender, the threat to his life seemed more probable. Before leaving Washington for some work, Lamon, his bodyguard had urged

__________________________

- Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, Compiled and Edited by Don E. and Virginia Fehrenbacher, p. 485

- Ibid., p. 485

- Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald, p. 592

- Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J.G. Holland, Chapter XXX

- Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Vol. 2, Michael Burlingame, p. 300

Death of Lincoln, surrounded by his cabinet, generals and family.

Painted and engraved by A.H. Ritchie

him to stay home in his absence. Indifferent for his safety as always, Lincoln disregarded these warnings and accompanied by Mary left for the Theatre that evening.

Booth had failed several times in his attempt to kidnap the president. This time he was determined to avenge the south. Being an actor he was able to enter the presidential box without difficulty. He locked the door from inside and drawing out his gun, inched up behind the president and shot him in the head at close range. It was around 10:13 pm.

He had an ambitious plan; two of his accomplices were instructed to kill Vice President Johnson and Secretary of State, Seward. One got cold feet and the other entered the home of Seward and knocking down his son and daughter, managed his way into his bedroom. Repeatedly stabbing Seward in the neck, he flew back downstairs slashing anyone who came in his way. Seward was saved by the metal brace he was wearing on account of a carriage accident a week earlier.

Lincoln slumped forward, Mary screamed, Colonel Rathbone went after Booth who slashed him with a dagger and leaping over the box, managed to escape. A couple of army doctors

present in the audience, carried out Lincoln to a boarding house across the street; the bullet was lodged behind his right eye; for the following nine hours doctors did their best. Mary sat beside him crying and begging him to speak. Most of his cabinet members except Seward gathered around him. Through the night his friends and colleagues poured in and sat weeping by his bedside. Charles Sumner, his supporter and agitator held his hand and cried. Stanton, eyes brimming with tears, checked himself from breaking down; as Secretary of War, he had to take over the reins and prevent the government from coming to a halt. Lincoln’s vital tenacity was so strong, said the doctors that he survived beyond the two hours they had predicted, given the nature of the injury.

At 7:22 am Lincoln breathed his last, — the final casualty of a war that tormented him through the years. As he stood by Lincoln’s deathbed, Stanton remarked, ‘Now he belongs to the ages.’

“His sun went down suddenly, and whelmed the country in a darkness which was felt by every heart; but far up the clouds sprang soon the golden twilight, flooding the heavens with radiance, and illuminating every uncovered brow with the hope of a fair to-morrow. The aching head, the shattered nerves, the anxious heart, the weary frame, are all at rest; and the noble spirit that informed them, bows reverently and humbly in the presence of Him in whom it trusted, and to whose work it devoted the troubled years of its earthly life…

“Never had the nation mourned so over a fallen leader. Not only Lincoln’s friends, but his legion of critics… now lamented his death and grieved for their country.’1 ‘From the sunniest hills of joy, the people went down weeping into the darkest valleys of affliction… Men met in the

__________________

- With MaliceToward None: a Life of Abraham Lincoln. S.B. Oates, p. 434

streets, and pressed each other’s hands in silence, or burst into tears… Millions felt that they had lost a brother, or a father, or a dear personal friend. It was a grief that brought the nation more into family sympathy than it had been since the days of the Revolution…’1

The White House threw open its doors to people to have one last look at that kind face; thousands came — ‘the rich and the poor, the white and the black, mingled their tokens of affectionate regard, and dropped side by side their tears upon the coffin. It was humanity weeping over the dust of its benefactor’.2

At his funeral in the White House, Rev. Dr. Gurley, speaking of the great national emergency in which Lincoln was called to power, said:

“He… saw his duty as the chief magistrate of a great and imperiled people; and he determined to do his duty and his whole duty, seeking the guidance, and leaning upon the arm, of Him… Yes, he leaned upon His arm. He recognized and received the truth that the kingdom is the Lord’s.”3

He was finally taken back home to Springfield, Illinois, with his dear son Willie to be buried by his side — on a return journey that four years ago had brought him to Washington as president elect.

Nothing could have been more apt than a quote read out by Bishop Simpson from Lincoln’s speech in 1859. Referring to the slave power he had said:

“Broken by it I too, may be, bow to it, I never will. The probability that we may fail in the struggle, ought not to deter us from the support of a cause, which I deem to be just; and it shall not deter me. If ever I feel the soul within

__________________________

- Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, by J.G. Holland, Chapter XXX

- Ibid., Chapter XXX

- Ibid., Chapter XXX

me elevate and expand to those dimensions not wholly unworthy of its Almighty Architect, it is when I contemplate the cause of my country, deserted by all the world besides, and I, standing up boldly and alone, and hurling defiance at her victorious oppressors.”1

________________________

1. The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln: Student and Book Club Edition, by Francis Fisher Browne

Excerpt from

Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln by J.G. Holland

“… We have seen a great popular government, poisoned in every department by the virus of treason, and

blindly and feebly tottering to its death, restored to health and soundness through the beneficent ministry of this true man, who left it with vigor in its veins, irresistible strength in its arms, the fire of exultation and hope in its eyes, and with such power and majesty in its step, that the earth shook

beneath its stately goings.

We have seen four millions of African bondmen who, groaning in helpless slavery when he received the crown of power, became freemen by his word before death struck that crown from his brow.

We have seen

the enemies of his country vanquished and suing for pardon; and the sneering nations of the world, whose incontinent contempt and spite were poured in upon him during the first years of his administration, becoming first silent, then respectful, and then unstinted in their admiration and approbation…

… Uninfluenced by popular clamor, and unbent by his own humane and Christian desire to see all men free, he did not speak the word of emancipation until his duty to the Constitution which he had sworn to protect and defend demanded it… It was not slowness, nor coldness, nor indifference that delayed the emancipation of the slaves. It was loyal, devoted, self-denying virtue…

… He knew and felt the weakness of human nature… Hence, he was patient with his enemies, and equally patient with equally unreasonable friends…

He has given them a statesman without a statesman’s craftiness,

a politician without a politician’s meanness, a great man without a great man’s vices,

a philanthropist

without a philanthropist’s impracticable dreams; a Christian without pretensions,

a ruler without the pride of place and power, an ambitious man without selfishness, and a successful man without vanity.

On the basis of such a manhood as this,

all the coming generations of the nation will not fail to build high and beautiful ideals of human excellence,

whose attractive power shall raise to a nobler level the moral sense and moral character of the nation.

This true manhood

— simple, unpretending, sympathetic with all humanity, and reverent toward God —

is among the noblest of the nation’s treasures; and through it, God has breathed,

and will continue to breathe, into the nation, the elevating and purifying power of

His own divine life.”

* * *

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet