Landmarks Of Hinduism - Vedas, Puranas And Thereafter

Vedas, Puranas and Thereafter

— Continuity and Change —

I

The Vedas stand out in Indian history as the Himalayas of spirituality and as the perennial source of multisided culture. The Vedic Samhitas bear witness to epical struggle and victory of the Vedic Rishis, and those Rishis are felt even today as the spirits who assist their offsprings as the new dawns repeat the old and lean forward in light to join the dawns of the future. And as we read the inner history of India, we find these great Rishis shaping and moulding new Rishis age after age and helping them to build the bridges between the past and future. Continuity and change mingle with each other in the great adventure of India which thus always remains at once ancient and new.

The secret of the unaging puissance of the Veda can be traced to the freshness with which the Rishis attempted to deal with the enigma of life and authenticity of knowledge that was discovered and applied for the solution of the perplexing paradoxes and contradictions of world-experience. These Rishis fathomed the deep waters of the three great oceans of consciousness, the ocean of dark inconscient in which darkness is shrouded in greater darkness, the ocean of the human consciousness, and the ocean of the superconscient, which is the goal of "the rivers of clarity and of the honeyed wave." A study of interrelationship of these three oceans enabled the Rishis to discover the

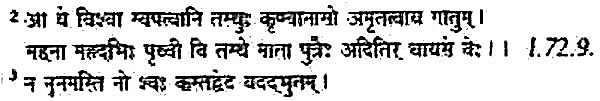

means by which one can overcome the life that is full of. untruth and attain to truth and immortality. In a symbolic and poetic chant, Vamadeva says that a honeyed wave climbs up from the ocean and by means of this mounting wave, which is the Soma (amshu), one attains entirely to immortality; he further says that that wave or that elixir is a secret name of the clarity (ghrita) he further says that it is the tongue of the Gods and it is the nodus of immortality.¹

Another great discovery of the Vedic Rishis was the secret of relationship between man and the cosmos. They discovered three earths of physical existence (prithvi) and three heavens of pure mind (dyau) and the intermediate Mid-region of life-force (antariksha); they discovered, at a still higher level, three luminous heavens of Swar, described variously in terms of the Truth, Right and Vast (satyam, ritam, brihat), and the supreme triple divine worlds. They discovered that the path to immortality is the path of truth and that this path is built by man's expansion into cosmic consciousness and by his interchange with cosmic powers who enable him to reach the Supreme creative consciousness, mother Aditi, who is one with the original substance, the Supreme Triple Reality. As Rishi Parashara explains:

"Our fathers broke open the firm and strong places by their words, yea, the Angirasas broke open the hill by their cry; they made in us the path to the great heaven; they found the Day and Swar and vision of the luminous Cows."

________________________________________

¹ समुद्राद् ऊर्मि: मधुमान् उदारद् उपांशुना सं अमृतत्वं आनद् ।

घृतस्य नाम गुह्यं यद् अस्ति । जिह्वा देवानां अमृतस्य नाभि: ॥ IV.58.1

He adds that this path is the path which leads to immortality. "They who enter all things that bear right fruits form a path towards the immortality; earth stood wide for them by the greatness and by Great Ones, the mother Aditi with her sons came (or, manifested herself) for the upholding."²

The secret of the interchange between man and the cosmic powers, which are called Devas in the Vedas, is the inner sacrifice of limitations so that the required room is increasingly made in human consciousness for the formation and establishment of the cosmic consciousness and all that transcends the cosmic consciousness.

The conquest of immortality, the Vedic Rishis discovered, involved also a long and difficult battle with formidable powers, Dasyus, Panis, Vritra; and the courage and heroism required in this battle imparted to the Vedic Rishis intimate knowledge of the intricacies of the web of the world as also of the knowledge of inner means by which the entanglements of the web could be disentangled and hold of adverse forces can be loosened and annulled.

But the loftiest discovery was that of the One, the mysterious and the wonderful, the eternal, unbound by Time and Space and unseizable even by the highest flights of Thought. As Indra declares:

"It is not now, nor is It tomorrow, who knoweth That which is Supreme and Wonderful? It has motion and action in the consciousness of another but when It is Broached by the thought It vanishes.'³

The complexity and the richness of the knowledge of the One becomes increasingly evident when we try to understand the great statement of Rishi Dirghatamas: ekam sad viprā bahudhā vadanti, the One that is variously described by the wise. The One, tad ekam, which was described in the Vedas as triple Divine came to be expressed in one complex word in the Upanishad " Sacchidananda”. A more detailed summary of the complexity of this One Reality was further articulated in intensely meaningful words, Brahman, Purusha, Ishwara with associated words: Maya, Prakriti, and Shakti. The Veda is replete with descriptions of this One Reality, and they invite us to transcend all superficial exercises of speculation so that by an act of meditative and experiential consciousness, we may try to enter into the inner mystery and wonder.

This subtle and complex concept of tad ekam lies at the root of the complex character of the Vedic Godheads which have been wholly misunderstood by those who ascribe to them only outer physical significance. Each of these Gods is in himself a complete and separate cosmic personality of the One existence, and in their combination of powers they form the complete universal power, the cosmic whole. Each again, apart from his special function, is the one godhead with the others; each holds in himself the universal divinity. Each God is all the other gods. This is the aspect of the Vedic teaching to which a European scholar has given the sounding misnomer henotheism. But the Veda goes on to say that these Godheads put on their highest nature in the triple Infinite and are names of the One nameless Ineffable.

_____________________________________________

1. अन्घस्य चित्तमभि संचरेण्यमुताधीतं वि नश्यति।। I.170.1

II

These lofty heights of knowledge which we find in the Vedas serve as the elements of continuity, and we find them or some of them in the same or different terms in all the succeeding developments of Indian religion and spirituality. Upanishads which were nearest to the Vedas have been acknowledged as the crown and end of the Veda; that is indicated in their general name, Vedanta. In the stress of the seeking which can be discerned from such records as the Chhandogya and Brihadaranayaka, the truths held by the Vedic Rishis broke their barriers which were present in the earlier system of communication, and they swept through the highest minds of the nation and fertilised the soil of Indian 'culture for a constant and ever-increasing growth of spiritual consciousness and spiritual experience. And even when this turn was still evident, chiefly among the Kshatriyas and Brahmins, we find too among those who attained to the knowledge men like Janashruti, the wealthy shudra or Satyakama Jabala, son of a servant girl who knew not who was his father.

The Upanishads mark both continuity and change. The Vedantic seers renewed the Vedic truth by extricating it from its cryptic symbols and casting it into a higher and most direct and powerful language of inner intuition and inner experience. It is true that the language of the Upanishads was not the language of the intellect, but still it wore a form which the intellect could take hold of, translate into its own more and abstract terms and convert into a starting-point for an ever- widening and deepening philosophical speculation and intellectual search after a truth original, supreme and ultimate. It was this Vedantic restatement of the Vedic knowledge that has served as the bedrock of-continuity,

and the Indian development of religion and spirituality was guided, up-lifted and more and more penetrated and suffused by the Vedantic saving power of spirituality.

The next stage of Indian civilisation, the post-Vedic stage was marked by a new climate as a result of the efflorescence of intellectual search and rise of great philosophies, many-sided epic literature, beginning of art and science, and evolution of vigorous and complex society. Also there emerged Buddhism, which seemed to reject all spiritual continuity with the Vedic roots. And yet, Indian religion, after absorbing all that it could of Buddhism, preserved the full line of its own continuity casting back to the ancient Vedanta.

Indeed, there was still a great change, but this change moved forward not by any destruction of principle, but by a gradual fading of the prominent Vedic forms and the substitution by others. The psychic and spiritual endeavour of the Vedic hymns disappeared into intense luminosity, but there grew up at the same time more wide and rich and complex psycho-spiritual inner life of Puranic and Tantric religions and Yoga.

III

It has been said that Puranas existed in ancient times in the Vedic age itself, but it was only in the post- Vedic age that they were entirely developed and became the characteristic and the principal literary expression of the religious spirit and it is to this period that we must attribute, not indeed all the substance but the main bulk and the existing shape of the Puranic writings. Whatever may be our ultimate judgement on the significance of the Puranas, it can be observed that Puranas as also Tantras which belong to this age contain in themselves the highest spiritual and physical

truths derived from the lofty realisations of the Veda and the Upanishads. These truths are not broken up and expressed in opposition to each other as in the debates of the thinkers, but synthesised by a fusion, relation, or grouping in a way most congenial to the catholicity of the Indian mind and spirit. This is mostly done in a form which might carry something of it to the popular imagination and feeling by a legend, tale, symbol, epilogue, miracle and parable. This method is, after all, simply a prolongation of the method of the Vedas, in another form and with a temperamental change. The system of the Puranic symbolism is constructed in terms of physical images and observances each with its psychical significance. The geography of the Puranas is expressly explained in the Puranas themselves as a rich poetic figure; it is a symbolic geography of the inner psychical universe. As in the Vedas, so in the Puranas, the cosmogony which is expressed sometimes in terms proper to the physical universe has a spiritual and psychological meaning and basis. The rich and endless profusion of Puranic stories have produced enormous effect in training the mass mind to respond to a psycho- religious and psycho-spiritual appeal that prepared a capacity for highest things. Not all the Puranas contain high substance uniformly, but on the whole, the poetic method employed is justified by the richness and power of the creation. Some of the Puranas are, indeed, excellent both in substance and style. The Bhagavata, for instance, which is strongly affected by the learned and more ornate literary form of speech, is an ' extraordinary production, full of subtleties, rich and deep thought and beauty. It is in the Bhagavata that we get the culmination of the emotional and aesthetic religions of Bhakti. The aim of the Bhaktiyoga was to take and transmute the emotional, the sensuous, even the sensual motion of the being into a psychical form

and to utilise these elements for the attainment of the joy of God's love, delight and beauty. In later Puranas, we see development of the aesthetic and erotic symbol, and as in the Bhagavata, it is given its full power to manifest its entire spiritual and philosophic as well as its psychic sense and to remould into its own line of a shifting of the centre of the synthesis from knowledge to spiritual love and delight the earlier significance of the Vedanta. The perfect outcome of this evolution is to be found in the philosophy and religion of divine love promulgated by Sri Chaitanya.

It is true that the Vedic Gods rapidly lost in the Puranas their deep original significance. The great Trinity, Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva came to dominate and gave rise to a new pantheon. It must, however, be remarked that the predominance of this Trinity was a result of the significance that was attached to these three Gods in the Veda. Brahma evidently developed out of Brahmanaspati, Vishnu was already recognised as the all-pervading Godhead and Vishnu has a close connection with Rudra or Shiva. It is true that in the Veda larger number of hymns were devoted to Agni and Indra, but the importance of the Vedic Gods should not be measured by the number of hymns devoted to them. In fact, Agni and Indra are not greater than Vishnu and Rudra. In the Veda, Vishnu, Rudra and Brahmanaspati provide the conditions of the Vedic work and assisted from behind the more present and active Gods. Brahmanaspati is the Creator by the word, and it is from this creative aspect of Brahmanaspati that the Puranic conception of Brahma, the Creator, arose. For the upward movement of Brahmanaspati's formations, Rudra supplies the force; he is named in the Veda the mighty one of heaven, but he begins his work upon the earth and gives effect to the sacrifice on the

five planes of our ascent. He is the Violent One who leads the upward evolution of the conscious being, his force battles against evils, smites the sinner and the enemy. Agni, Kumara, prototype of the Puranic Skanda, is on earth the child of this force of Rudra. In these and many other aspects which are described in the Veda, we have all the materials necessary for the evolution of puranic Shiva-Rudra, the Destroyer and Healer, the Auspicious and Terrible, the Master of the force that acts in the worlds and the Yogin who enjoys the supreme liberty and peace. While Brahmanaspati’s word creates and Rurdra’s force supplies the force, Vishnu provides the necessary static element. He supplies the ordered movement of the worlds and the highest goals. The Veda speaks of Vishnu's three strides by which he establishes all the worlds. The Veda tells us that Vishnu pervades all these worlds and gives less or greater room to the actions and movements of the Gods. Here, again, the Vedic Vishnu is a natural precursor and sufficient origin of the Puranic Narayana, Preserver and Lord of Love.

In the Vedic religion, ritualistic sacrifice occupied the central place. In the Puranic tradition, the Vedic sacrifice persisted only in broken and lessening fragments. The house of fire was replaced by the temple, the Karmic ritual of sacrifice was transformed into the devotional temple ritual. The Physical images of the two great deities, Vishnu and Shiva, and their Shaktis and their offshoots were used to stabilise their psychological functions, and they were made the basis both for internal adoration and for their eternal worship. Here, again, it may be mentioned that image worship seems to have developed from the Vedic concept of how man takes the cosmic powers that are acting in the Universe upon himself, makes an image of

them in his own consciousness and endows that image with the life and power that the Supreme Being has breathed into His own Divine forms and world energies. It is for this reason that Indian image worship is not the idolatry of a barbaric or undeveloped mind, for even the most ignorant knows that the image is a symbol of support and can be set aside when its use is over.

A great contribution of the Puranas is the celebration of the inner presence of the Divine in the universe and in man. The Vedic concept of the sacrifice of Purusha which is one of the mysteries of the Vedic tradition, can be seen to be the precursor of the concept of the Divine avatara which has played a major role in the epical and Puranic literature of India. Here, too, we can see the continuity of the Veda in the Puranas.

IV

Inner significance of the Puranas can be appreciated when we realise that the Puranic religion was an effort, successful in a great measure, to open the general mind of the people to a higher and deeper range of inner truth, experience and feeling. It was a catholic attempt to draw towards the spiritual truth minds of all qualities and people of all classes. While much was lost of the profound psychic knowledge of the Vedic seers, much also of new knowledge was developed, untrodden ways were opened and a hundred gates discovered into the Infinite. Puranas attempted to lay hold on the inner vital and emotional nature, to awaken a more inner mind even in the common man, and to lead him through these things towards a higher spiritual truth. The Puranic system, along with the Tantric, was a wide, assured and many-sided endeavour. It can be said that it was unparalleled in its power, insight, amplitude, to provide the race with a basis of generalised psycho-religious

experience from which man could rise through knowledge, works or love or through any other fundamental power of his nature to some established supreme experience and highest absolute status.

Much of the adverse criticism of the Puranas emanates from the lack or neglect of the intention that lay behind the Purano-Tantric forms of worship and of the mythological method employed in the literary works. Much of this criticism has been concentrated on side-paths and aberrations which could hardly be avoided in this immensely audacious experimental widening of the basis of the culture. At the same time, it is easy to see how in the increasing ignorance of later times the more technical parts of the Puranic symbology inevitably lent themselves to much superstition and to crude physical ideas about spiritual and psychic things.

The Vedic system of different planes of existence and corresponding worlds remained fundamentally unaltered in the Puranas. The Puranas refer to the seven principles of existence and the seven worlds correspond to them with sufficient precision. The principle of pure existence, sat, corresponds to the world of highest truth of the being (Satyaloka); the principle of pure consciousness, Chit, corresponds to the world of infinite will or conscious force (Tapoloka); the principle of pure bliss ananda, corresponds to the world of creative slight of existence (Jnanaloka); the principle of knowledge or Truth, vijnana, corresponds to the world of vastness (Maharloka); the principle of mind, which was Dyau in the Vedas corresponds to the Puranic world of light (Swar); the principle of life which in the Veda was the Principle of antariksha corresponds to the world of various becoming (Bhuvar); and the principle of matter, prithvi, corresponds to the material world (Bhur). The

cosmic gradations in the Veda correspond with those in the Puranas although they were differently grouped, - seven worlds in principle, five in practice, three in their general groupings.

Just as the Veda is concerned with the application of inner knowledge to the solution of the practical problems of life, even so, the Puranas aim at the exposition of the highest knowledge and they also aim at inspiring increasing number of people to apply that knowledge in fighting battles of life. As the Veda is an account of the inner battle of life with Vritra Vala and Panis, even so Puranas give an account of the battle between Gods, Devas and their enemies Asuras, Rakshasas and Pishachas. As the Veda speaks of immortality as the goal, even so Puranas speak of the conquest of the elixir of life and attainment of undying celestial joy.

In spite of the great change in the colour and climate in the deeper and wider ranges of experience there is a continuity between the Veda and the Puranas.

V

The great effort of the Puranas or the Purano-Tantric age covered all the time between the Vedic age and the decline of Buddhism. But this was not the last possibility of the evolution of religion in India. It appears that there is a hidden design in the development of Indian religion. It certainly aims to mediate between God and man, but it wants to train all aspects of man all sections of human society, and all ranges of the potentialities so that God can manifest in all His aspects in man's physical life. The Vedic stage prepared the natural external man for spirituality. The Second stage which covers the Puranic period takes up his outward life into a deeper mental and psychical living and brings

him more directly into contact with the spirit and divinity within him. The post-Puranic age aimed at rendering him capable of taking up his whole mental, psychical, physical living into a first beginning at least of a generalised spiritual life. This work had already begun, and this was signified by the outburst of philosophies, great spiritual movements of saints and bhaktas and an increasing resort to various paths of Yoga. But before this task could proceed further, there began unhappy decline of Indian culture and because of increasing collapse of general vitality and knowledge, it could not bear its natural fruit. But still the work which was done was extremely important and it has created a great possibility for the future. In the changing situation of today, once again the theme of continuity and change has become extremely important. We need to understand once again the inner heart and soul of the Veda, the inner heart and soul of the Puranas and Tantras, and also inner heart and soul of the post- Puranic age with its great movements of Bhakti and multisided Yoga. And we have to open ourselves to make the treasures of the past as our support for unfinished task of the integral divinisation of human life and nature. It seems that India's mission is to work out the widest and highest spiritualising of life on earth, even by going beyond all exclusive and limiting boundaries of religions or religionism, and it is in that direction that India can move forward, if it is to fulfil the mission of her deepest soul.