Philosophy of Indian Art - Philosophy of Indian art

Philosophy of Indian Art

From various accounts which have evidential value, it is clear that India pursued the quest of the knowledge and the experience of reality through a multiple and even integral approach. The basic quest of India was to discover the causes of disintegration and to find effective remedies by which disintegration can be prevented. In positive terms, this was the quest for immortality, and the ancient literature gives us convincing proof of this quest as also of the victory that was attained. We also find accounts of the processes by which this victory was attained. In this process the major role was played by a difficult psychological discipline in which thought power, will power, and affective power were so elevated and perfected that higher realms of comprehensive knowledge and power were discovered and possessed. Truth, Right, and Vast – satyam, ritam, brihat – these three words constituted the formula of the process and the victory. This process was so comprehensive that every gate of inquiry was required to be opened up and explored. And it is for this reason that the basic science of this quest, namely the science of Yoga, included pursuit of Dharma, Darshan, Shastra as also

Philosophy of Indian Art

From various accounts which have evidential value, it is clear that India pursued the quest of the knowledge and the experience of reality through a multiple and even integral approach. The basic quest of India was to discover the causes of disintegration and to find effective remedies by which disintegration can be prevented. In positive terms, this was the quest for immortality, and the ancient literature gives us convincing proof of this quest as also of the victory that was attained. We also find accounts of the processes by which this victory was attained. In this process the major role was played by a difficult psychological discipline in which thought power, will power, and affective power were so elevated and perfected that higher realms of comprehensive knowledge and power were discovered and possessed. Truth, Right, and Vast – satyam, ritam, brihat – these three words constituted the formula of the process and the victory. This process was so comprehensive that every gate of inquiry was required to be opened up and explored. And it is for this reason that the basic science of this quest, namely the science of Yoga, included pursuit of Dharma, Darshan, Shastra as also Kalā. Hence, the range of cultural activities of India centred on the quest of spiritual truth but it also promoted quest through science, philosophy, art and several other means. Intense spirituality, robust scientific and philosophical intellectuality and powerful literature, poetry, art and inexhaustible vitality have marked the essential characteristics of Indian culture.

. Hence, the range of cultural activities of India centred on the quest of spiritual truth but it also promoted quest through science, philosophy, art and several other means. Intense spirituality, robust scientific and philosophical intellectuality and powerful literature, poetry, art and inexhaustible vitality have marked the essential characteristics of Indian culture.

If our educational system is to reflect these characteristics of our culture, we must have full provision for pursuit of all these aspects, so that our students can be recipients of our true Indian heritage.

Just as science is a quest of truth, just as philosophy is a quest of truth, even so art, too, is a quest of truth. But each one of them has its own specific method which distinguishes it from all others. The chief characteristics of scientific method are that of observation, experimentation and verification as also expansion by progressive inquiry. The essence of philosophical method is exploration of the realm of ideas, of eternity and infinity, of essence of universality and individuality, and a comprehensive approach to grasp the totality and reality not merely through speculation but particularly through investigation of the significance and meaning of the totality of experience, so that what is thought is also attempted to be realised and experienced and utilised for the enhancement of the fulfilment of life. Art is also characterised by a quest, but its chief characteristic is to fathom the depths of experience of an object or a field until the depths of experience begin to vibrate with images appropriate to the object of experience. This fathoming of the depths of experience reveals the truth of the object but it also inspires formulations that can express themselves variously so as to give us special techniques and cannons of art forms such as painting, sculpture, architecture, music, poetry and others. Art is a voyage of discovery and expression, a voyage inspired and marked by joy, love and beauty, a voyage that brings us closest to the inner recesses of consciousness and unites in its expression the inner and the outer in such a way that the

formulations lead the artist and the viewer or the hearer to something that is within us in order to hear the inaudible, to see the invisible and to seize the unseizeable.

This is the boon of art, and the bounty of this boon we should be able to shower on all the seekers, particularly students and teachers of all ages.

Considering that our present system of education has no place or only peripheral place for art education, it is imperative that we explore the philosophy of art, the philosophy of Indian art in particular, and the values that art education can furnish in the process of a total development of personality.

There are certain essential elements that are the distinguishing features of art and art experience. There is, first, intuition of the artist, – intuition that marks the awakening in an experience that unites the self of the artist and the object on which the artist concentrates. This experience may be at various levels, ranging from a contact to a penetration leading up to an identity. Again, this experience is marked by a sincerity which is intensified at deeper and deeper levels. The result of the experience is the discovery of the truths of the object and the discovery of the beauty of the object. This beauty vibrates in the consciousness in a state of joy, in a state of feeling, in a state of rasa of creation and some kind of inevitability of the expression of form through a technique that is appropriate to the given form of art. Form and technique are interrelated and they demand each other in their road towards perfection. At a given stage of expression and creativity, they assume great importance, and the great

masterpieces of art embody these elements and determine their excellence.

There is, we might say, mystery, miracle and magic of form, and the joy of the artist, the creativeness of the artist is in the discovery and expression of this mystery, miracle and magic. The artist arrives in the great stress of experience at the origin of the form, where the form seems to emerge from the womb of the formless, from the reality that is ineffable, which is yet no monotone and which is not devoid of potency, but is capable of power, and of multiple formations of significant symbolism. Art is thus essentially a journey to the secret where the unseizeable is seized, where significant forms are discovered and expressed. The subtlest experience of art consists in arriving at the subtlety of the relationship between the form and the formless, the finite and the infinite, the qualified and the unqualified, the conditioned and the unconditioned. But this subtlety has degrees, and there are ways and manners, and there are levels at which this subtlety is grasped and expressed. The differences of manners and levels lie at the root of differences among art traditions, different habits of creation and different modes of appreciation. In one of the traditions, the artist gets his intuition of a suggestion from an appearance in life and nature, and even when it starts from something deeper, he relates it at once to an external support. Often this results in a colourable imitation of life and nature. In another tradition, the artist begins with the intuition or contact or experience at deeper levels, something that is true of the Indian or Chinese or Japanese tradition, and these starting points make a difference in the creativity of forms and in the emphasis that

one lays in expressing the inner and the truer, the inner being or the inner form of the object.

Every artistic creation has an object and a field of the intuitive vision or of the depth of experience; every artistic creation has a method of working out the vision or experience or suggestions of vision or experience; and every artistic creation is marked by the vibration of the vision or experience into the mode of its rendering by the external form and technique, and every artistic creation has behind it something holistic, both in its composition and its appeal, in the manner in which the creation is rendered to the human mind and how it is related to the centre of the being to which the artistic work is intended to appeal.

If we now ask the question as to what distinguishes Indian art, and what is the central philosophy of Indian art as we can gather it from the rich and long course of history through which that art has been sustained through several millennia, we shall find that it is a self-conscious endeavour in which aesthetic experience and aesthetic creativity as also beauty, joy and love were discovered at the loftiest and deepest recesses of the deeper soul in its expansion towards universality and infinity. The spirit, motive and aim of Indian art is to render the sense of infinity, and the sense of cosmocity through symbolic forms, forms that are subtle, forms which are symbolic and forms which are distinctive and which may correspond, in varying degrees, to the external forms which nature has fashioned in its own creative and artistic play. In the following lines, Sri Aurobindo brings out briefly but precisely the theory of ancient Indian art at its greatest.

“Its highest business is to disclose something of the Self, the Infinite, the Divine to the regard of the soul, the Self through its expressions, the Infinite through its living finite symbols, the Divine through his powers. Or the Godheads are to be revealed, luminously interpreted or in some way suggested to the soul's understanding or to its devotion or at the very least to a spiritually or religiously aesthetic emotion. When this hieratic art comes down from these altitudes to the intermediate worlds behind ours, to the lesser godheads or genii, it still caries into them some power or some hint from above. And when it comes quite down to the material world and the life of man and the things of external Nature, it does not altogether get rid of the greater vision, the hieratic stamp, the spiritual seeing, and in most good work – except in moments of relaxation and a humorous or vivid play with the obvious ¬ there is always something more in which the seeing presentation of life floats as in an immaterial atmosphere. Life is seen in the self or in some suggestion of the infinite or of something beyond or there is at least a touch and influence of these which helps to shape the presentation. It is not that all Indian work realises this ideal; there is plenty no doubt that falls short, is lowered, ineffective or even debased, but it is the best and the most characteristic influence and execution which gives its tone to an art and by which we must judge.”1

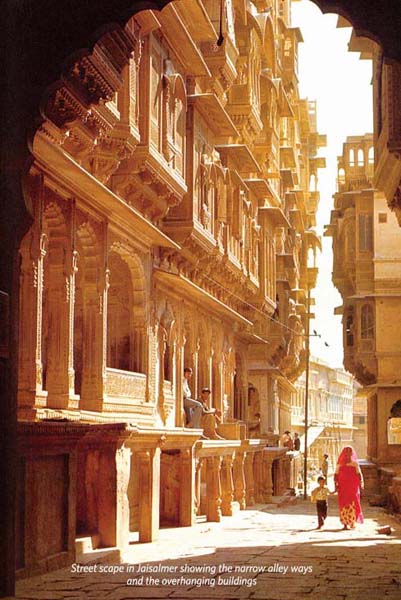

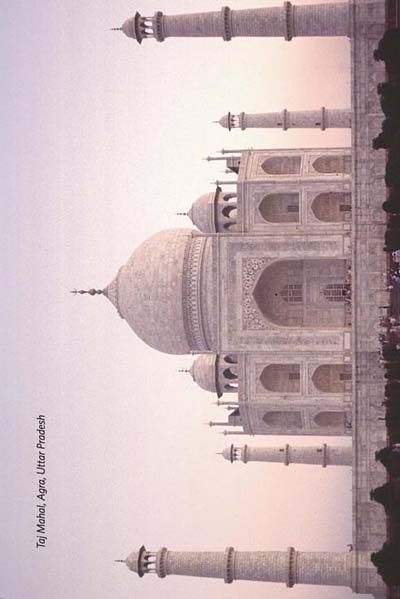

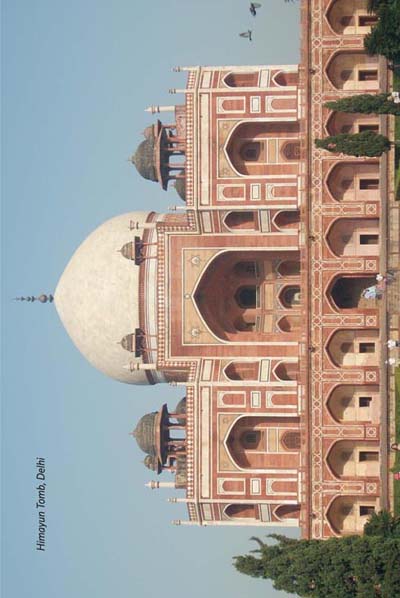

Indian architecture, particularly Indian sacred architecture, in its inmost reality is an altar raised to the Divine Self, a House of Cosmic Spirit, an appeal and inspiration to the Infinite. Symbolism is the main characteristic of Indian architecture, and this is true even of the Indo-Muslim architecture, where

1 Sri Aurobindo: The Foundations of Indian Culture, Centenary Edition, Volume 14, p.208

the Indian mind has taken in much from the Arab and the Persian imagination. As Sri Aurobindo points out in regard to the Taj Mahal:

“The Taj is not merely a sensuous reminiscence of an imperial amour or a fairy enchantment hewn from the moon's lucent quarries, but the eternal dream of a love that survives death.”2

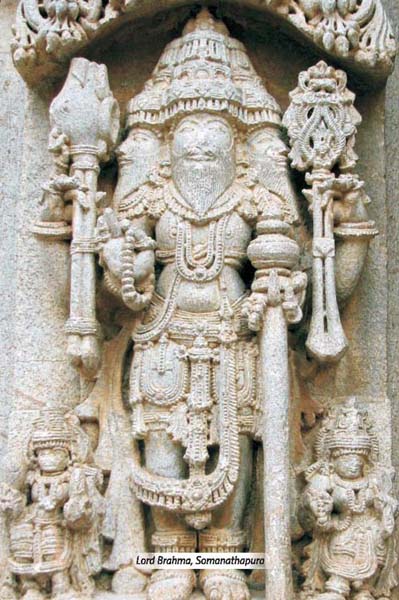

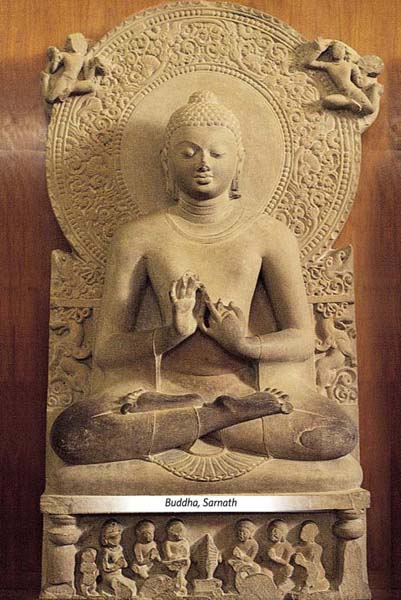

Indian sculpture, particularly the more ancient sculptural art, springs from spiritual realisation, and what it creates and expresses at its greatest is the spirit in form, the soul in body, this or that living soul-power in the Divine or the human, the universal and the cosmic individualised suggestion but not lost in individuality. Its aim is not to express the ideal physical or emotional beauty, but the utmost spiritual beauty or the significance of which the human form is capable. Soul-realisation is its method and soul realisation must be the way of our response and understanding. The statute of a king or a saint is not merely meant to give the idea of a king or a saint or to portray some dramatic action or to be a character portrait in a scene, but to embody rather a soul-state or experience or deeper soul-quality. This is what we find in the great Buddhas or the Natrajas. The figure of the Buddha expresses the infinite in a finite image, embodies the illimitable calm of Nirvana in human form envisaged. The Kālasamhāra Shiva expresses the majesty, pure calm and forceful control, dignity, and kingship of existence. The pose of the figure visibly incarnates that whole spirit of the cosmic Shiva. Again, the cosmic dance of Shiva expresses the cosmic movement and delight, and the posture of every limb is made to bring out the realm and significance, the rapturous intensity and fullness of the movement.

2 Ibid., p.224.

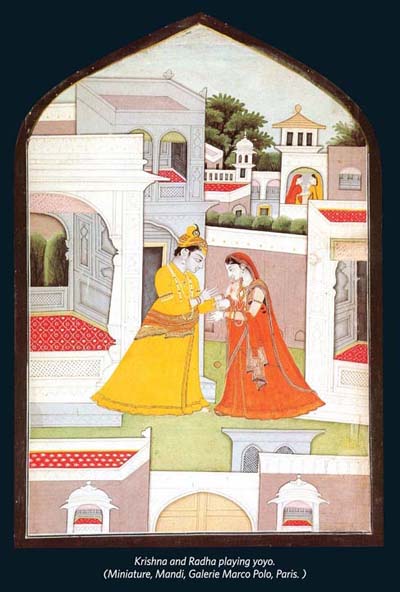

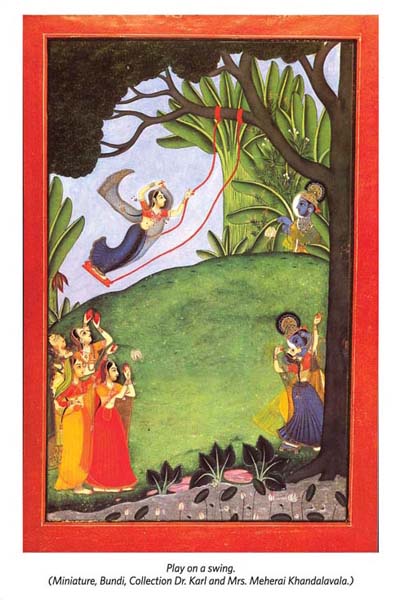

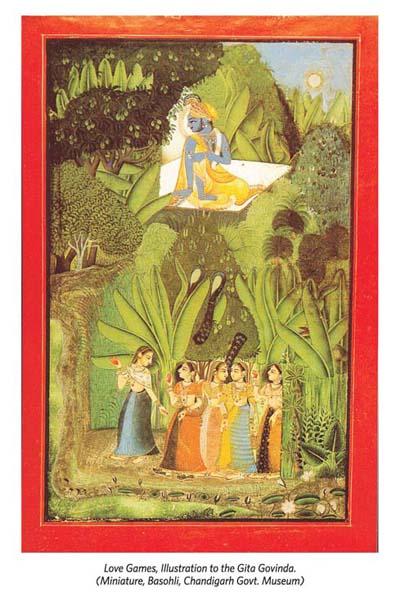

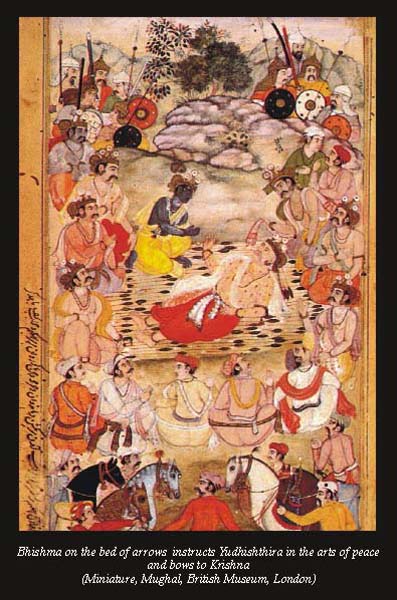

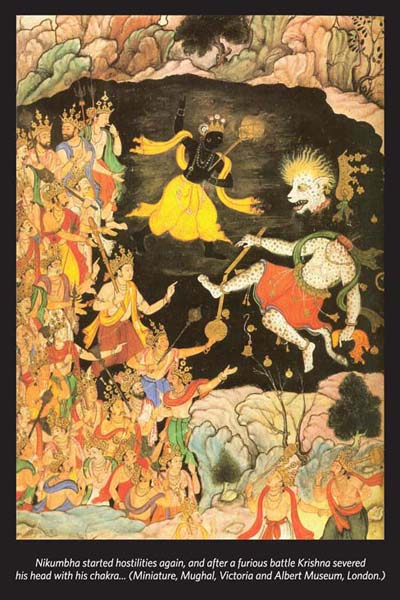

The art of painting in later India covers a long period of more than two thousand years. Long before the Christian Era began, we find the theory of the art well founded from previous times, where six essential elements, shadańga, were recognised and enumerated. Historically, reference in ancient literature also indicates a widespread practice and appreciation of the art of painting by both men and women of the cultural classes. Even the later Rajput work continues the spirit and depth of the interpretation of spirituality, religion, culture and life of the Indian people.

The six essential elements described in the Indian shastra of Indian painting can be considered to be something that is common in painting everywhere. But the Indian shastra gives us the evidence of self-consciousness of the Indian painting that was presented since early times. The six limbs of Indian art refer, first, to the distinction of forms, rupa-bheda; secondly, to proportion, arrangement of line and mass, design, harmony, perspective, pramāna; thirdly, to the emotion or aesthetic feeling expressed by the form, bhāva; fourthly, for seeking for beauty and charm for the satisfaction of the aesthetic spirit, lāvanya; fifthly, to the truth of the form and its suggestion, sadrishya; sixthly, to the turn, combination, harmony of colours, varnikabhańga. The distinctive character of Indian art, however, emerges from the turn given to each of the constituents of shadańga.

Let us try to understand this distinctive character of the Indian art of painting. Rupa-bheda in the Indian art is faithfully observed. But here there is no attempt at an exact naturalistic fidelity to the physical appearance; the objects are not

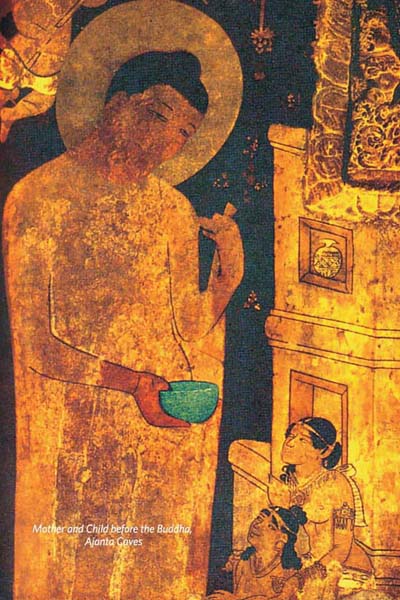

reproduced in the image of the outward shapes of the world in which we live. Indeed, there is vividness, naturalness, reality, but it is more than a physical reality. We do not turn to Indian painting in order to study the science of anatomy. We turn to study the reality of the soul, to experience a vivid naturalness of psychic truth. We turn to it to perceive the convincing spirit of the form to which the soul bears witness. What is repeated is the truth of the essence of the form, the reproduction of the subtle embodiment which is the basis of the physical embodiment, the purer and finer subtle body of an object which expresses its own essential nature, swabhāva. This is brought out very clearly in the paintings of Ajanta and of Bagh and other frescos. We find here the pure and strong outline and suppression of what would blur and dilute the intense significance of the line. The whole essential human being is present in the human figure but what is brought out is the divinity that has taken this garb of the spirit, which is visible to the eye. We find the ideal psychical figure in its charm and beauty. The line is filled in by a disposition of pure masses, design and colour and wave-flow of the body. What is expressed is the one spiritual emotion, feeling, suggestion which the artist intends to convey. Particularly, hands are used in a miraculously subtle and meaningful way so that the psychic suggestion is expressed, and the face and the eyes are expressed psychically and the same expression is supplemented by the expression of the hands. We find in the Indian painting the law of significant line and suppression of distracting detail even when it is applied to the animal forms, buildings, trees, objects. There is an inspired harmony of conception, method and expression. Even colour is used as a

means for spiritual and psychic intention. There is a union of greatness and moving grace and this continues even in the Rajput paintings, although the vividness and suggestiveness of the line are bolder and more decisive. Form in the Indian paintings emerges from the deeper source of the soul and the spirit rather than from the external and physical nature.

Pramāna,proportion, harmony and perspective follow the same inner law of formulation of the inner form, of the inner atmosphere, of the inner dimensions. Bhāva in Indian painting is the expression of the universal spiritual essence of the emotion modified by the essential soul-type that is presented in the image. Complexity of the dramatic insistence is avoided, and so much stress is only laid on character in the individual feeling as to give the variation without diminishing the unity of the fundamental emotion. Emotion is transmitted directly from the spirit to our own spirit, but in later art, a greater stress is laid on the psychic thought and feeling which are thrown outward in movement; but still the soul-motive is constitutive of the whole atmosphere. This is true even where the subject is not spiritual or religious but secular. Lāvanya in Indian painting is again a charm and beauty of that which is subtle, of that which is psychic and spiritual. Physical beauty is not the only beauty in the world; this truth is vividly illustrated in the Indian painting. The deeper we travel in the heart and thought, in the soul and in the spirit, the deeper we travel from the form to the formless, and from the individual to the universal, the greater is the aesthetics, the greater is the charm, the greater is the harmony, the greater is the beauty and the underlying rasa of the experience of art. Sadrishya,

varnikabhańga and rupa-bheda are all correlated to each other, and what is to be appreciated is not only the technique or the fervour of the deeper and of psychic feeling. What is to be appreciated is the intent served by the technique, the psychic significance of line and colour and the whole purpose of the artist.

I should like to present a citation from Sri Aurobindo in order to illustrate how we should look at an Indian painting and how its real spirit is to be grasped. Sri Aurobindo has given us an analysis of the adoration group of the mother and the child before the Buddha, which according to Sri Aurobindo is one of the most profound, tender and noble of the Ajanta paintings.

“That which it deepens to is the turning of the soul of humanity in love to the benignant and calm Ineffable which has made itself sensible and human to us in the universal compassion of the Buddha, and the motive of the soul-moment the painting interprets is the dedication of the awakening mind of the child, the coming of younger humanity, to that in which already the soul of the mother had learned to find and fix its spiritual joy. The eyes, brows, lips, face, poise of the head of the woman are filled with this spiritual emotion which is a continued memory and possession of the psychical release, the steady settled calm of the heart's experience filled with an ineffable tenderness, the familiar depths which are yet moved with the wonder and always farther appeal of something that is infinite, the body and other limbs are grave masses of this emotion and in their poise a basic embodiment of it, while the hands prolong it in

the dedicative putting forward of her child to meet the Eternal. This contact of the human and eternal is repeated in the smaller figure with a subtly and strongly indicated variation, the glad and childlike smile of awakening which promises but not yet possesses the depths that are to come, the hands disposed to receive and keep, the body in its looser curves and waves harmonising with that significance. The two have forgotten themselves and seem almost to forget and confound each other in that which they adore and contemplate, and yet the dedicating hands unite mother and child in the common act and feeling by their simultaneous gesture of maternal possession and spiritual giving. The two figures have at each point the same rhythm, but with a significant difference. The simplicity in the greatness and power, the fullness of expression gained by reserve and suppression and concentration which we find here is the perfect method of the classical art of India. And by this perfection Buddhist art became not merely an illustration of the religion and an expression of its thought and its religious feeling, history and legend, but a revealing interpretation of the spiritual sense of Buddhism and its profounder meaning to the soul of India.”3

Art opens the gates of our consciousness to the depths of truth and beauty; it imparts to our consciousness the sense and experience of joy and love and adoration and uplifts us into realms of purity, restraint, balance and equilibrium. And if truth is beauty and beauty is goodness, art is a great builder of character. If we wish to overcome excesses of desires and passions, if we wish to refine our roughness and indecency in action and manner, and if at the same we wish to overcome

3 Ibid., pp.250-51.

excesses of soulless ceremony and formalism, of privation and dryness of temperament, and if we wish to attain the golden mean where the true virtue resides, we must enthrone art education in our system in its fullness.

Science of living and art of living can best be cultivated in the brain and in the heart and in our entire being through art education. Indeed, art through art education can bring our students nearer to the experience of rasa that constantly flows in all aspects of life and in all circumstances. At the highest level, pursuit of beauty is the pursuit of ānanda, and ānanda is a source of akhanda rasa, undifferentiated and unabridged delight and delightfulness in things. We can prepare a road to this goal by the pursuit of poetry, music and art at lower levels at first and gradually at higher and higher levels of experience and contemplation. Even in the training of the intellectual faculty, art can play a great role. Subtlety is the soul of art, and art education makes the mind also in its movement subtle and delicate. Art is suggestive, and the intellect that is habituated to the appreciation of art is quick to catch suggestions; the intellect that has been refined by the experience of art can easily be led to master not only the surface reality and appearances but also that which leads to ever-fresh widening and subtlising of knowledge. For art opens a door into the deeper secrets of inner nature which the instrument of science cannot measure. Above all, art takes us beyond reaches of thought and morality and takes us deeper into spiritual truths and into the joy and God in the world as also the beauty and desirableness of the manifestation of divine force and energy in phenomenal creation. Indian art, particularly, provides a

ready means through which body, heart and mind can be brought into touch with the Spirit. That is the reason why, if the Indian system of education is to become truly Indian, Indian art and its great heritage should be brought into the very life of our students and teachers.

It is not necessary that every student should be trained to become an artist. But it is necessary that every student should be given facilities to develop his or her artistic faculty and to train his or her taste and also to refine his or her sense of beauty and the insight of form and colour. It is also necessary that those who create should be habituated to produce higher forms of art. Our endeavour should be such that the nation is habituated to accept the beautiful in preference to the ugly, the noble in preference to the vulgar, the fine in preference to the crude, the harmonious in preference to the gaudy. In the words of Sri Aurobindo:

“A nation surrounded daily by the beautiful, noble, fine and harmonious becomes that which it is habituated to contemplate and realises the fullness of the expanding Spirit in itself.”4

4 Sri Aurobindo: National Value of Art, Centenary Edition, Volume 17, p.251