Arguments for The Existence of God - Proofs Of The Existence Of God And Of The Human Soul

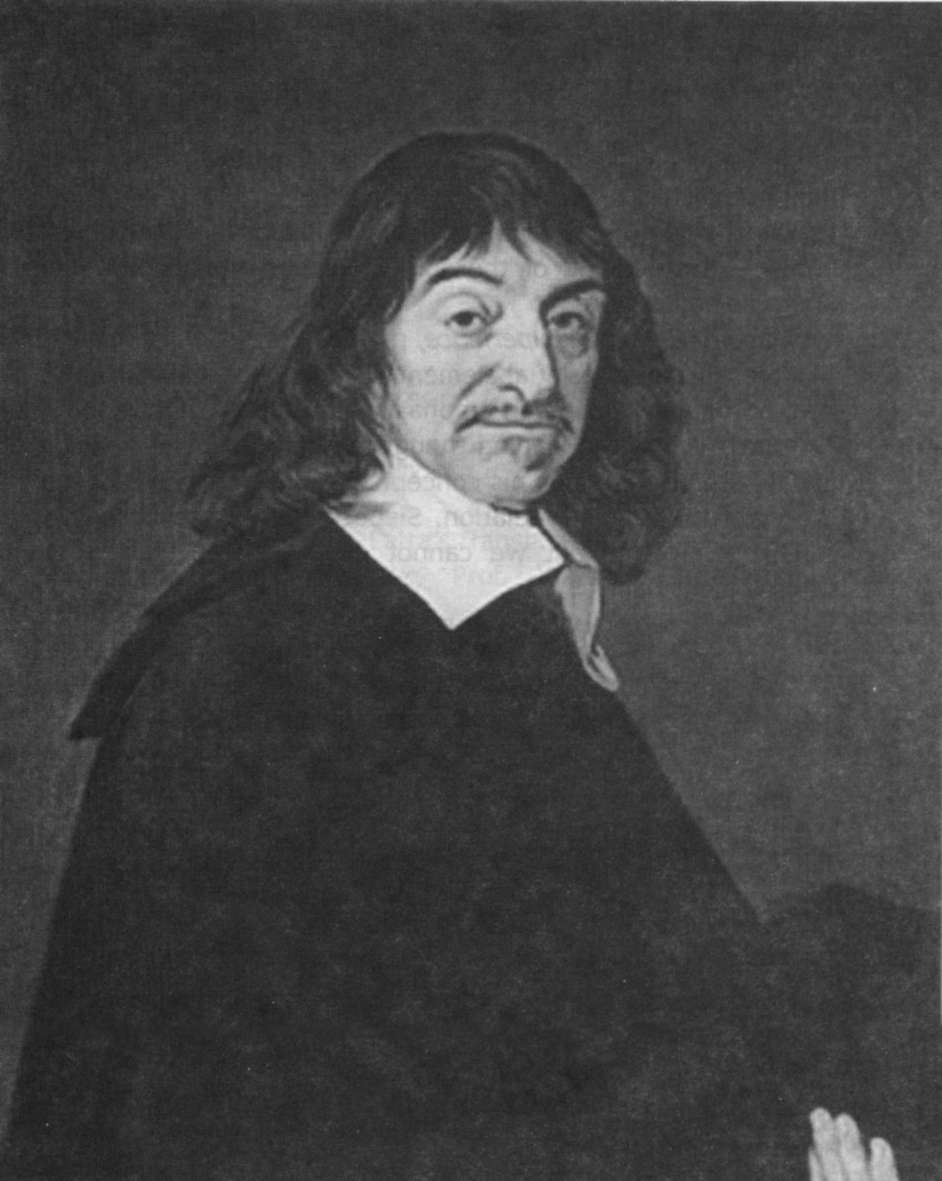

Rene Descartes

Proofs of the Existence of God

and of the Human Soul

Ido not know whether I ought to touch upon my first meditations here, for they are so metaphysical and out of the ordinary that they might not be interesting to most people. Nevertheless, in order to show whether my fundamental notions are sufficiently sound, I find myself more or less constrained to speak of them. I had noticed for a long time that in practice it is sometimes necessary to follow opinions which we know to be very uncertain, just as though they were indubitable, as I stated before; but inasmuch as I desired to devote myself wholly to the search for truth, I thought that I should take a course precisely contrary, and reject as absolutely false anything of which I could have the least doubt, in order to see whether anything would be left after this procedure which could be called wholly certain. Thus, as our senses deceive us at times, I was ready to suppose that nothing was at all the way our senses represented them to be. As there are men who make mistakes in reasoning even on the simplest topics in geometry, I judged that I was as liable to error as any other, and rejected as false all the reasoning which I had previously accepted as valid demonstration. Finally, as the same precepts which we have when awake may come to us when asleep without their being true, I decided to suppose that nothing that had ever entered my mind was more real than the illusions of my dreams. But I soon noticed that

while I thus wished to think everything false, it was necessarily true that I who thought so was something. Since this truth, I think, therefore I am, was so firm and assured that all the most extravagant suppositions of the sceptics were unable to shake it, I judged that I could safely accept it as the first principle of the philosophy I was seeking.

I then examined closely what I was, and saw that I could imagine that I had no body, and that there was no world nor any place that I occupied, but that I could not imagine for a moment that I did not exist. On the contrary, from the very fact that I doubted the truth of other things, it followed very evidently and very certainly that I existed. On the other hand, if I had ceased to think while all the rest of what I had ever imagined remained true, I would have had no reason to believe that I existed; therefore I concluded that I was a substance whose whole essence or nature was only to think, and which, to exist, has no need of space nor of any material thing. Thus it follows that this ego, this soul, by which I am what I am, is entirely distinct from the body and is easier to know than the latter, and that even if the body were not, the soul would not cease to be all that it now is.

Next I considered in general what is required of a proposition for it to be true and certain, for since I had just discovered one to be such, I thought I ought also to know of what that certitude consisted. I saw that there was nothing at all in this statement, "I think, therefore I am," to assure me that I was saying the truth, unless it was that I saw very clearly that to think one must exist. So I judged that I could accept as a general rule that the things which we conceive very clearly and very distinctly are always true, but that there may well be some difficulty in deciding which are those which we conceive distinctly.

After that I reflected upon the fact that I doubted, and that, in consequence, my spirit was not wholly perfect, for I saw clearly that it was a greater perfection to know than to doubt. I decided to ascertain from what source I have learned to think

of something more perfect than myself, and it appeared evident that it must have been from some nature which was in fact more perfect. As for my ideas about many other things outside of me, as the sky, earth, light, heat, and thousands of other things, I was not so much troubled to discover where they came from, because I found nothing in them superior to my own nature. If they really existed, I could believe that whatever perfection they possessed might be derived from my own nature; if they did not exist, I could believe that they were derived from nothingness, that is, that they were derived from my own defects. But this could not be the explanation of my idea of a being more perfect than my own. To derive it from nothingness was manifestly impossible, and it is no less repugnant to good sense to assume what is more perfect comes from and depends on the less perfect than it is to assume that something comes from nothing, so that I could not assume that it came from myself. Thus the only hypothesis left was that this idea was put in my mind by a nature that was really more perfect than I was, which had all the perfections that I could imagine, and which was, in a word, God. To this I added that since I knew some perfections which I did not possess, I was not the only being in existence (I will here use freely, if you will pardon me, the terms of the schools), and that it followed of necessity that there was someone else more perfect upon whom I depended and from whom I had acquired all that I possessed. For if I had been alone and independent of anything else, so that I had bestowed upon myself all that limited quantity of value which I shared with the perfect Being, I would have been able to get from myself, in the same way, all the surplus which I recognise as lacking in me, and so would have been myself infinite, eternal, immutable, omniscient, omnipotent, and, in sum, I would possess all the perfections that I could discover in God.

For, following the reasoning which I have just explained, to know the nature of God as far as I was capable of such knowledge, I had only to consider each quality of which I had an idea,

and decide whether it was or was not a perfection to possess it. I would then be certain that none of those which had some imperfection was in him, but that all the others were. I saw that doubt, inconstancy, sorrow and similar things could not be part of God's nature, since I would be happy to be without them myself. In addition, I had ideas of many sensible and corporeal entities, for although I might suppose that I was dreaming and that all that I saw or imagined was false, I could not at any rate deny that the ideas were truly in my consciousness. Since I had already recognised very clearly that intelligent nature is distinct from corporeal nature, I considered that composition is an evidence of dependency and that dependency is manifestly a defect. From this I judged that it could not be a perfection in God to be composed of these two natures, and that consequently he was not so composed. But if there were in the world bodies, or even intelligences or other natures that were not wholly perfect, their being must depend on God's power in such a way that they could not subsist without him for a single moment.

At this point I wished to seek for other truths, and proposed for consideration the object of the geometricians. This I conceived as a continuous body, or a space infinitely extended in length, breadth, and height or depth; divisible into various parts which can have different shapes and sizes and can be moved or transposed in any way: all of which is presumed by geometricians to be true of their object, I went through some of their simplest demonstrations and noticed that the great certainty which everyone attributes to them is only based on the fact that they are evidently conceived, following the rule previously established. I noticed also that there was nothing at all in them to assure me of the existence of their object; it was clear, for example, that if we posit a triangle, its three angles must be equal to two right angles, but there was nothing in that to assure me that there was a single triangle in the world. When I turned back to my idea of a perfect Being, on the other hand, I discovered that existence was included in that

idea in the same way that the idea of a triangle contains the equality of its angles to two right angles, or that the idea of a sphere includes the equidistance of all its parts from its centre. Perhaps, in fact, the existence of the perfect Being is even more evident. Consequently, it is at least as certain that God, who is this perfect Being, exists, as any theorem of geometry could possibly be.

What makes many people feel that it is difficult to know of the existence of God, or even of the nature of their own souls, is that they never consider things higher than corporeal objects. They are so accustomed never to think of anything without picturing it — a method of thinking suitable only for material objects — that everything which is not picturable seems to them unintelligible. This is also manifest in the fact that even philosophers hold it as a maxim in the schools that there is nothing in the understanding which was not first in the senses, a location where it is clearly evident that the ideas of God and of the soul have never been. It seems to me that those who wish to use imagery to understand these matters are doing precisely the same thing that they would be doing if they tried to use their eyes to hear sounds or smell odours. There is even this difference: that the sense of sight gives us no less certainty of the truth of objects than do those of smell and hearing, while neither our imagery nor our senses could assure us of anything without the co-operation of our understanding.

Finally, if there are still some men who are not sufficiently persuaded of the existence of God and of their souls by the reasons which I have given, I want them to understand that all the other things of which they might think themselves more certain, such as their having a body, or the existence of stars and of an earth, and other such things, are less certain. For even though we have a moral assurance of these things, such that it seems we cannot doubt them without extravagance, yet without being unreasonable we cannot deny that, as far as metaphysical certainty goes, there is sufficient room for doubt. For we can imagine, when asleep, that we have another body

and see other stars and another earth without there being any such. How could one know that the thoughts which come to us in dreams are false rather than the others, since they are often no less vivid and detailed? Let the best minds study this question as long as they wish, I do not believe they can find any reason good enough to remove this doubt unless they presuppose the existence of God. The very principle which I took as a rule to start with, namely, that all those things which we conceived very clearly and very distinctly are true, is known to be true only because God exists, and because he is a perfect Being, and because everything in us comes from him. From this it follows that our ideas or notions, being real things which come from God insofar as they are clear and distinct, cannot to that extent fail to be true. Consequently, though we often have ideas which contain falsity, they can only be those ideas which contain some confusion and obscurity, in which respect they participate in nothingness. That is to say, they are confused in us only because we are not wholly perfect. It is evident that it is not less repugnant to good sense to assume that falsity or imperfection as such is derived from God, as that truth or perfection is derived from nothingness. But if we did not know that all reality and truth within us came from a perfect and infinite Being, however clear and distinct our ideas might be, we would have no reason to be certain that they were endowed with the perfection of being true.

After the knowledge of God and the soul has thus made us certain of our rule, it is easy to see that the dreams which we have when asleep do not in any way cast doubt upon the truth of our waking thoughts. For if it happened that we had some very distinct idea, even while sleeping, as for example when a geometrician dreams of some new proof, his sleep does not keep the proof from being good. As for the most common error of dreams, which is to picture various objects in the same way as our external senses represent them to us, it does not matter if this gives us a reason to distrust the truth of the impressions we receive from the senses, because we can also be mistaken

in them frequently without being asleep, as when jaundiced persons see everything yellow, or as the stars and other distant objects appear much smaller than they really are. For in truth, whether we are asleep or awake, we should never allow ourselves to be convinced except on the evidence of our reason. Note that I say of our reason, and not of our imagination or of our senses; for even though we see the sun very clearly, we must not judge thereby that its size is such as we see it, and we can well imagine distinctly the head of a lion mounted on the body of a goat, without concluding that a chimera exists in this world. For reason does not insist that all we see or visualise in this way is true, but it does insist that all our ideas or notions must have some foundation in truth, for it would not be possible that God, who is all-perfect and wholly truthful, would otherwise have given them to us. Since our reasonings are never as evident or as complete in sleep as in waking life, although sometimes our imaginations are then as lively and detailed as when awake, or even more so, and since reason tells us also that all our thoughts cannot be true, as we are not wholly perfect; whatever of truth is to be found in our ideas will inevitably occur in those which we have when awake rather than in our dreams.

Text from Descartes' Discourse on Method,

translated by J. Lafleur

(New York: The Library of Liberal Arts, second edition, 1956),

pp. 20-26.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet