Joan of Arc - Joan Of Arc

Joan of Arc

Extracts from Joan of Arc by Marc Twain

Well, anything to make delay. The King's council advised him against arriving at a decision in our matter too precipitately. He arrives at a decision too precipitately! So they sent a committee of priests—always priests—into Lorraine to inquire into Joan's character and history— a matter which would consume several weeks, of course. You see how fastidious they were. It was as if people should come to put out the fire when a man's house was burning down, and they waited till they could send into another country to find out if he had always kept the Sabbath or not, before letting him try.

So the days poked along, dreary for us young people in some ways, but not in all, for we* had one great anticipation in front of us—we had never seen a king, and now some day we should have that prodigious spectacle to see and to treasure in our memories all our lives; so we were on the look-out, and always eager and watching for the chance. The others

-----------------

*We : a small group of mostly young men who have accompanied Joan in her journey from Vaucouleurs to Chinon to meet the King. Among them are two brothers of Joan, Jean and Pierre d'Arc, the narrator, Louis Le Come, childhood friend of Joan (later, her page and secretary), and two members of the nobility, Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy who were touched very early by Joan's determination and purity.

were doomed to wait longer than I, as it turned out. One day great news came—the Orleans commissioners, with Yolande and our knights, had at last turned the council's position and persuaded the King to see Joan.

Joan received the immense news gratefully but without losing her head, but with us others it was otherwise; we could not eat or sleep or do any rational thing for the excitement and the glory of it. During two days our pair of noble knights were in distress and trepidation on Joan's account, for the audience was to be at night, and they were afraid that Joan would be so paralysed by the glare of light from the long files of torches, the solemn pomps and ceremonies, the great con- course of renowned personages, the brilliant costumes, and the other splendours of the Court that she, a simple country maid, and all unused to such things, would be overcome by these terrors and make a piteous failure.

No doubt I could have comforted them, but I was not free to speak. Would Joan be disturbed by this cheap spectacle, this tinsel show, with its small King and his butterfly dukelets?— she who had spoken face to face with the princes of heaven, the familiars of God, and seen their retinue of angels stretching back into the remoteness of the sky, myriads upon myriads, like a measureless fan of light, a glory like the glory of the sun streaming from each of those innumerable heads, the massed radiance filling the deeps of space with a blinding splendour? I thought not.

Queen Yolande wanted Joan to make the best possible impression upon the King and the Court, so she was strenuous to have her clothed in the richest stuffs, wrought upon the princeliest pattern, and set off with jewels; but in that she had to be disappointed, of course, Joan not being persuadable to it, but begging to be simply and sincerely dressed, as became a servant of God, and one sent upon a mission of a serious sort and grave political import. So then the gracious Queen imagined and contrived that simple and witching costume which I have described to you so many times, and which I cannot

think of even now in my dull age without being moved just as rhythmical and exquisite music moves one; for that was music, that dress — that is what it was—music that one saw with the eyes and felt in the heart. Yes, she was a poem, she was a dream, she was a spirit when she was clothed in that.

She kept that raiment always, and wore it several times upon occasions of state, and it is preserved to this day in the Treasury of Orleans, with two of her swords, and her banner, and other things now sacred because they had belonged to her.

At the appointed time the Count of Vendome, a great lord of the Court, came richly clothed, with his train of servants and assistants, to conduct Joan to the King, and the two knights and I went with her, being entitled to this privilege by reason of our official positions near her person.

When we entered the great audience hall, there it all was, just as I have already painted it. Here were ranks of guards in shining armour and with polished halberds; two sides of the hall were like flower-gardens for variety of colour and the magnificence of the costumes; light streamed upon these masses of colour from two hundred and fifty flambeaux. There was a wide free space down the middle of the hall, and at the end of it was a throne royally canopied, and upon it sat a crowned and sceptred figure nobly clothed and blazing with jewels.

It is true that Joan had been hindered and put off a good while, but now that she was admitted to an audience at last, she was received with honours granted to only the greatest person- ages. At the entrance door stood four heralds in a row, in splendid tabards, with long slender silver trumpets at their mouths, with square silken banners depending from them embroidered with the arms of France. As Joan and the Count passed by, these trumpets gave forth in unison one long rich note, and as we moved down the hall under the pictured and gilded vaulting, this was repeated at every fifty feet of our progress—six times in all. It made our good knights proud and happy, and they held themselves erect, and stiffened their stride, and looked fine and soldierly. They were not expecting this beautiful and honourable tribute to our little country maid.

Entry of castle at Chinon

Joan walked two yards behind the Count, we three walked two yards behind Joan. Our solemn march ended when we were as yet some eight or ten steps from the throne. The Count made a deep obeisance, pronounced Joan's name, then bowed again and moved to his place among a group of officials near the throne. I was devouring the crowned person- age with all my eyes, and my heart almost stood still with awe.

The eyes of all others were fixed upon Joan in a gaze of wonder which was half worship, and which seemed to say, 'How sweet—how lovely—how divine!' All lips were parted and motionless, which was a sure sign that those people, who seldom forget themselves, had forgotten themselves now, and were not conscious of anything but the one object they were gazing upon. They had the look of people who are under the enchantment of a vision.

Then they presently began to come to life again, rousing themselves out of the spell and shaking it off as one drives away little by little a clinging drowsiness or intoxication. Now they fixed their attention upon Joan with a strong new interest of another sort; they were full of curiosity to see what she would do—they having a secret and particular reason for this curiosity. So they watched. This is what they saw:

She made no obeisance, nor even any slight inclination of her head, but stood looking toward the throne in silence. That was all there was to see, at present, I glanced up at De Metz, and was shocked at the paleness of his face. I whispered and said: 'What is it, man; what is it?'

His answering whisper was so weak I could hardly catch it:

'They have taken advantage of the hint in her letter to play a trick upon her! She will err, and they will laugh at her. That is not the King that sits there.'

Then I glanced at Joan. She was still gazing steadfastly toward the throne, and I had the curious fancy that even her shoulders and the back of her head expressed bewilderment. Now she turned her head slowly, and her eye wandered along the lines of standing courtiers till it fell upon a young man who was very quietly dressed; then her face lighted joyously, and she ran and threw herself at his feet, and clasped his knees, exclaiming in that soft melodious voice which was her birthright and was now charged with deep and tender feeling:

'God of His grace give you long life, O dear and gentle Dauphin!'

In his astonishment and exultation De Metz cried out:

'By the shadow of God, it is an amazing thing!' Then he mashed all the bones of my hand in his grateful grip, and added, with a proud shake of his mane, 'Now, what have these painted infidels to say!'

Meantime the young person in the plain clothes was saying to Joan:

'Ah, you mistake, my child, I am not the King. There he is,' and he pointed to the throne.

The knight's face clouded, and he muttered in grief and indignation:

'Ah, it is a shame to use her so. But for this lie she had gone through safe. I will go and proclaim to all the house what—'

'Stay where you are!' whispered I and the Sieur Bertrand in a breath, and made him stop in his place.

Joan did not stir from her knees, but still lifted her happy face toward the King, and said:

'No, gracious liege, you are he, and none other.'

De Metz's troubles vanished away, and he said:

'Verily, she was not guessing, she knew. Now, how could she know? It is a miracle. I am content, and will meddle no more, for I perceive that she is equal to her occasions, having that in her head that cannot profitably be helped by the

vacancy that is in mine.'

This interruption of his lost me a remark or two of the other talk; however, I caught the King's next question:

'But tell me who you are, and what would you?'

'I am called Joan the Maid, and am sent to say that the King of Heaven wills that you be crowned and consecrated in your good city of Rheims, and be thereafter Lieutenant of the Lord of Heaven, who is King of France. And He willeth also that you set me at my appointed work and give me men-at-arms.' After a slight pause she added, her eye lighting at the sound of her words, 'For then will I raise the siege of Orleans and break the English power!'

The young monarch's amused face sobered a little when this martial speech fell upon that sick air like a breath blown from embattled camps and fields of war, and his trifling smile presently faded wholly away and disappeared. He was grave now, and thoughtful. After a little he waved his hand lightly, and all the people fell away and left those two by themselves in a vacant space. The knights and I moved to the opposite side of the hall and stood there. We saw Joan rise at a sign, then she and the King talked privately together.

All that host had been consumed with curiosity to see what Joan would do. Well, they had seen, and now they were full of astonishment to see that she had really performed that strange miracle according to the promise in her letter; and they were fully as much astonished to find that she was not overcome by the pomps and splendours about her, but was even more tranquil and at her ease in holding speech with a monarch than ever they themselves had been, with all their practice and experience.

As for our two knights, they were inflated beyond measure with pride in Joan, but nearly dumb, as to speech, they not being able to think out any way to account for her managing to carry herself through this imposing ordeal without ever a mistake or an awkwardness, of any kind to mar the grace and credit of her great performance.

The talk between Joan and the King was long and earnest, and held in low voices. We could not hear, but we had our eyes and could note effects; and presently we and all the house noted one effect which was memorable and striking, and has been set down in memoirs and histories and in testimony at the Process of Rehabilitation by some who witnessed it; for all knew it was big with meaning, though none knew what that meaning was at that time, of course. For suddenly we saw the King shake off his indolent attitude and straighten up like a man, and at the same time look immeasurably astonished. It was as if Joan had told him something almost too wonderful for belief, and yet of a most uplifting and welcome nature.

It was long before we found out the secret of this conversation, but we know it now, and all the world knows it. That part of the talk was like this—as one may read in all histories. The perplexed King asked Joan for a sign. He wanted to believe in her and her mission, and that her Voices were supernatural and endowed with knowledge hidden from mortals; but how could he do this unless these Voices could prove their claim in some absolutely unassailable way? It was then that Joan said:

'I will give you a sign, and you shall no more doubt. There is a secret trouble in your heart which you speak of to none—a doubt which wastes away your courage, and makes you dream of throwing all away and fleeing from your realm. Within this little while you have been praying, in your own breast, that God of His grace would resolve that doubt, even if the doing of it must show you that no kingly right is lodged in you.'

It was that that amazed the King, for it was as she had said:

his prayer was the secret of his own breast, and none but God could know about it. So he said:

'The sign is sufficient. I know, now, that these Voices are of God. They have said true in this matter; if they have said more, tell it me—I will believe.'

'They have resolved that doubt, and I bring their very words, which are these: Thou art lawful heir to the King thy father, and true heir of France. God has spoken it. Now lift up thy head, and doubt no more, but give me men-at-arms and let me

get about my work.'

Telling him he was of lawful birth was what straightened him up and made a man of him for a moment, removing his doubts upon that head, and convincing him of his royal right;and if any could have hanged his hindering and pestiferous council and set him free, he would have answered Joan's prayer and set her in the field. But no, those creatures were only checked, not checkmated; they could invent some more delays.

We had been made proud by the honours which had so distinguished Joan's entrance into that place—honours restricted to personages of very high rank and worth—but that pride was as nothing compared with the pride we had in the honour done her upon leaving it. For whereas those first honours were shown only to the great, these last, up to this time, had been shown only to the royal. The King himself led Joan by the hand down the great hall to the door, the glittering multitude standing and making reverence as they passed, and the silver trumpets sounding those rich notes of theirs. Then he dismissed her with gracious words, bending low over her hand and kissing it. Always—from all companies, high or low—she went forth richer in honour and esteem than when she came.

And the King did another handsome thing by Joan, for he sent us back to Coudray Castle torch-lighted and in state, under escort of his own troop—his guard of honour—the only soldiers he had; and finely equipped and bedizened they were, too, though they hadn't seen the colour of their, wages since they were children, as a body might say. The wonders which Joan had been performing before the King had been carried all around by this time, so the road was so packed with people who wanted to get a sight of her that we could hardly dig through; and as for talking together, we couldn't, all attempts at talk being drowned in the storm of shoutings and huzzas that broke out all along as we passed, and kept abreast of us like a wave the whole way.

(...) When Joan told the King what that deep secret was that was torturing his heart, his doubts were cleared away; he believed she was sent of God/and if he had been let alone he would have set her upon her great mission at once. But he was not let alone. Tremouille and the holy fox of Rheims knew their man. All they needed to say was this—and they said it:

'Your Highness says her Voices have revealed to you, by her mouth, a secret known only to yourself and God. How can you know that her Voices are not of Satan, and she his mouth- piece?—for does not Satan know the secrets of men and use his knowledge for the destruction of their souls? It is a dangerous business, and your Highness will do well not to proceed in it without probing the matter to the bottom.'

That was enough. It shrivelled up the King's little soul like a raisin, with terrors and apprehensions, and straightway he privately appointed a commission of bishops to visit and question Joan daily until they should find out whether her supernatural helps hailed from heaven or from hell.

The King's relative, the Duke of Alencon, three years prisoner of war to the English, was in these days released from captivity through promise of a great ransom; and the name and fame of the Maid having reached him—for the same filled all mouths now, and penetrated to all parts—he came to Chinon to see with his own eyes what manner of creature she might be. The King sent for Joan and introduced her to the Duke. She said, in her simple fashion:

'You are welcome; the more of the blood Of France that is joined to this cause, the better for the cause and it.'

Then the two talked together, and there was just the usual result: when they parted, the Duke was her friend and advocate.

Joan attended the King's mass the next day, and afterward dined with the King and the Duke. The King was learning to prize her company and value her conversation; and that might well be, for, like other kings, he was used to getting nothing out of people's talk but guarded phrases, colourless and non- committal, or carefully tinted to tally with the colour of what he said himself; and so this kind of conversation only vexes and bores, and is wearisome; but Joan's talk was fresh and free, sincere and honest, and unmarred by timorous self-watching and constraint. She said the very thing that was in her mind, and said it in a plain, straightforward way. One can believe that to the King this must have been like fresh cold water from the mountains to parched lips used to the water of the sunbaked puddles of the plain.

After dinner Joan so charmed the Duke with her horsemanship and lance practice in the meadows by the Castle of Chinon, whither the King also had come to look on, that he made her a present of a great black war-steed.

Every day the commission of bishops came and questioned Joan about her Voices and her mission, and then went to the King with their report. These pryings accomplished but little. She told as much as she considered advisable, and kept the rest to herself. Both threats and trickeries were wasted upon her. She did not care for the threats, and the traps caught nothing. She was perfectly frank and childlike about these things. She knew the bishops were sent by the King, that their questions were the King's questions, and that by all law and custom a King's questions must be answered; yet she told the King in her naive way at his own table one day that she answered only such of those questions as suited her.

The bishops finally concluded that they couldn't tell whether Joan was sent by God or not. They were cautious, you see. There were two powerful parties at Court; therefore to make a decision either way would infallibly embroil them with one of those parties; so it seemed to them wisest to roost on the fence and shift the burden to other shoulders. And that is what they

did. They made final report that Joan's case was beyond their powers, and recommended that it be put into the hands of the learned and illustrious doctors of the University of Poitiers. Then they retired from the field, leaving behind them this little item of testimony, wrung from them by Joan's wise reticence: they said she was a 'gentle and simple little shepherdess, very candid, but not given to talking.'

It was quite true—in their case. But if they could have looked back and seen her with us in the happy pastures of Domremy, they would have. perceived that she had a tongue that could go fast enough when no harm could come of her words.

So we travelled to Poitiers, to endure there three weeks of tedious delay while this poor child was being daily questioned and badgered before a great bench of—what? Military experts?— since what she had come to apply for was an army and the privilege of leading it to battle against the enemies of France. Oh no; it was a great bench of priests and monks—profoundly learned and astute casuists—renowned professors of theology! Instead of setting a military commission to find out if this valorous little soldier could win victories, they set a company of holy hair-splitters and phrasemongers to work to find out if the soldier was sound in her piety and had no doctrinal leaks. The rats were devouring the house, but instead of examining the cat's teeth and claws, they only concerned themselves to find out if it was a holy cat. If it was a pious cat, a moral cat, all right, never mind about the other capacities, they were of no consequence.

Joan was as sweetly self-possessed and tranquil before this grim tribunal, with its robed celebrities, its solemn state and imposing ceremonials, as if she were but a spectator and not herself on trial. She sat there, solitary on her bench, untroubled, and disconcerted the science of the sages with her sublime ignorance—an ignorance which was a fortress; arts, wiles, the learning—drawn from books, and all like missiles rebounded from its unconscious masonry and fell to the ground harmless;

they could not dislodge the garrison which was within— Joan's serene great heart and spirit, the guards and keepersof her mission.

She answered all questions frankly, and she told all the story of her visions and of her experiences with the angels and what they said to her; and the manner of the telling was so unaffected, and so earnest and sincere, and made it all seem so life-like and real, that even that hard practical Court forgot itself and sat motionless and mute, listening with a charmed and wondering interest to the end. And if you would have other testimony than mine, look in the histories and you will find where an eye- witness, giving sworn testimony in the Rehabilitation process, says that she told that tale 'with a noble dignity and simplicity,' and as to its effect, says in substance what I have said. Seventeen, she was—seventeen, and all alone on her bench by herself; yet was not afraid, but faced that great company of erudite doctors of law and theology, and by the help of no art learned in the schools, but using only the enchantments which were hers by nature, of youth, sincerity, a voice soft and musical, and an eloquence whose source was the heart, not the head, she laid that spell upon them. Now was not that a beautiful thing to see? If I could, I would put it before you just as I saw it; then I know what you would say.

As I have told you, she could not read. One day they harried and pestered her with arguments,—reasonings, objections and other windy and wordy trivialities, gathered out of the works of this and that and the other great theological authority, until at last her patience vanished, and she turned upon them sharply and said:

'I don't know A from B; but I know this: that I am come by command of the Lord of Heaven to deliver Orleans from the English power and crown the King at Rheims, and the matters ye are puttering over are of no consequence!'

Necessarily those were trying days for her, and wearing for everybody that took part; but her share was the hardest, for she had no holidays, but must be always on hand and stay the

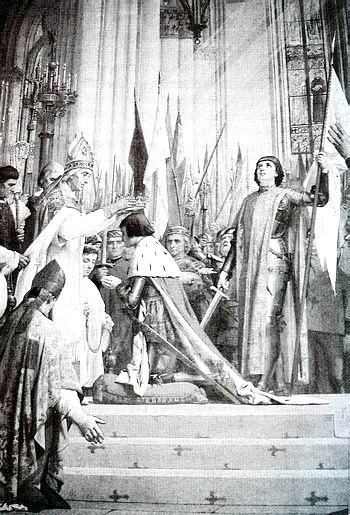

Joan of Arc by William Blake Richmond (1842-1921)

long hours through, whereas this, that, and the other inquisitor could absent himself and rest up from his fatigues when he got worn out. And yet she showed no wear, no weariness, and but seldom let fly her temper. As a rule she put her day through calm, alert, patient, fencing with those veteran masters of scholarly sword-play and coming out always without a scratch.

One day a Dominican sprung upon her a question which made everybody cock up his ears with interest; as for me, I trembled, and said to myself she is caught this time, poor Joan, for there is no way of answering this. The sly Dominican began in this way—in a sort of indolent fashion, as if the thing he was about was a matter of no moment:

'You assert that God has willed to deliver France from this English bondage?'

'Yes, He has willed it.'

'You wish for men-at-arms, so that you may go to the relief of Orleans, I believe?'

'Yes—and the sooner the better.'

'God is all-powerful, and able to do whatsoever thing He wills to do, is it not so?'

'Most surely. None doubts it.'

The Dominican lifted his head suddenly, and sprung that question I have spoken of, with exultation:

'Then answer me this. If He has willed to deliver France, and is able to do whatsoever He wills, where is the need for men-at-arms?'

There was a fine stir and commotion when he said that, and a sudden thrusting forward of heads and putting up of hands to ears to catch the answer; and the Dominican wagged his head with satisfaction, and looked about him collecting his applause, for it shone in every face. But Joan was not disturbed. There was no note of disquiet in her voice when she answered:

He helps who help themselves. The sons of France will fight the battles, but He will give the victory!'

You could see a light of admiration sweep the house from face to face like a ray from the sun. Even the Dominican himself looked pleased, to see his master-stroke so neatly parried, and I heard a venerable bishop mutter, in the phrasing common to priest and people in that robust time, 'By God, the child has said true. He willed that Goliath should be slain, and He sent a child like this to do it!'

Another day, when the inquisition had dragged along until everybody looked drowsy and tired but Joan, brother Seguin, professor of theology in the University of Poitiers, who was a sour and sarcastic man, fell to plying Joan with all sorts of nagging questions in his bastard Limousin French—for he was from Limoges. Finally he said:

'How is it that you could understand those angels? What language did they speak?'

'French.'

'In-deed! How pleasant to know that our language is so honoured! Good French?'

'Yes—perfect.'

'Perfect, eh? Well, certainly you ought to know. It was even better than your own, eh?'

'As to that, I—I believe I cannot say,' said she, and was going on, but stopped. Then she added, almost as if she were saying it to herself, 'Still, it was an improvement on yours!'

I knew there was a chuckle back of her eyes, for all their innocence. Everybody shouted. Brother Seguin was nettled, and asked brusquely:

'Do you believe in God?'

Joan answered with an irritating nonchalance:

'Oh, well, yes—better than you, it is likely.'

Brother Seguin lost his patience, and heaped sarcasm after sarcasm upon her, and finally burst out in angry earnest, exclaiming:

'Very well, I can tell you this, you whose belief in God is so great: God has not willed that any shall believe in you without a sign. Where is your sign?—show it'

This roused Joan, and she was on her feet in a moment, and flung out her retort with spirit:

'I have not come to Poitiers to show signs and do miracles. Send me to Orleans and you shall have signs enough. Give me men-at-arms—few or many—and let me go!'

The fire was leaping from her eyes—ah, the heroic little figure! Can't you see her? There was a great burst of acclamations, and she sat down blushing, for it was not in her delicate nature to like being conspicuous.

This speech and that episode about the French language scored two points against Brother Seguin, while he scored nothing against Joan; yet, sour man as he was, he was a manly man, and honest, as you can see by the histories; for at the Rehabilitation he could have hidden those unlucky incidents if he had chosen, but he didn't do it, but spoke them right out in his evidence.

On one of the later days of that three weeks' session the gowned scholars and professors made one grand assault all along the line, fairly overwhelming Joan with objections and arguments culled from the writings of every ancient and illustrious authority of the Roman Church. She was well nigh smothered; but at last she shook herself free and struck back, crying out:

'Listen! The Book of God is worth more than all these ye cite, and I stand upon it. And I tell ye there are things in that Book that not one among ye can read, with all your learning!'

From the first she was the guest, by invitation, of the dame De Rabateau, wife of a councillor of the Parliament of Poitiers; and to that house the great ladies of the city came nightly to see Joan and talk with her; and not these only, but the old lawyers, councillors, and scholars of the Parliament and the University. And these grave men, accustomed to weigh every strange and questionable thing, and cautiously consider it, and turn it about this way and that and still doubt it, came night after night, and night after night, falling ever deeper and deeper under the influence of that mysterious something, that spell,

that elusive and unwordable fascination, which was the supremest endowment of Joan of Arc, that winning and persuasive and convincing something which high and low alike recognised and felt, but which neither high nor low could explain or describe; and one by one they all surrendered, saying 'This child is sent of God.'

All day long Joan, in the great court and subject to its rigid rules of procedure, was at a disadvantage; her judges had things their own way; but at night she held court herself, and matters were reversed, she presiding, with her tongue free and her same judges there before her. There could be but one result; all the objections and hindrances they could build around her with their hard labours of the day she would charm away at night. In the end, she carried her judges with her in a mass, and got her great verdict without a dissenting voice.

The court was a sight to see when the president of it read it from his throne, for all the great people of the town were there who could get admission and find room. First there were some solemn ceremonies, proper and usual at such times; then, when there was silence again, the reading followed, penetrating the deep hush so that every word was heard in even the remotest parts of the house:

'It is found, and is hereby declared, that Joan of Arc, called the Maid, is a good Christian and good Catholic; that there is nothing in her person or her words contrary to the faith; and that the King may and ought to accept the succour she offers; for to repel it would be to offend the Holy Spirit, and render him unworthy of the aid of God.'

The court rose, and then the storm of plaudits burst forth unrebuked, dying down and bursting forth again and again, and I lost sight of Joan, for she was swallowed up in a great tide of people who rushed to congratulate her and pour out benedictions upon her and upon the cause of France, now solemnly and irrevocably delivered into her little hands.

It was indeed a great day, and a stirring thing to see.

She had won! It was a mistake of Tremouille and her other ill-wishers to let her hold court those nights.

The commission of priests sent to Lorraine ostensibly to inquire into Joan's character—in fact to weary her with delays and wear out her purpose and make her give it up—arrived back and reported her character perfect. Our affairs were in full career now, you see.

The verdict made a prodigious stir. Dead France woke suddenly to life, wherever the great news travelled. Whereas before, the spiritless and cowed people hung their heads and slunk away if one mentioned war to them, now they came clamouring to be enlisted under the banner of the Maid of Vaucouleurs, and the roaring of war songs and the thundering of the drums filled all the air. I remembered now what she had said, that time there in our village when I proved by facts and statistics that France's case was hopeless, and nothing could ever rouse the people from their lethargy:

'They will hear the drums—and they will answer, they will march!'

It has been said that misfortunes never come one at a time, but in a body. In our case it was the same with good luck. Having got a start it came flooding in, tide after tide. Our next wave of it was of this sort. There had been grave doubts among the priests as to whether the Church ought to permit a female soldier to dress like a man. But now came a verdict on that head. Two of the greatest scholars and theologians of the time—one of whom had been Chancellor of the University of Paris—rendered it. They decided that since Joan 'must do the work of a man and a soldier, it is just and legitimate that her apparel should conform to the situation.'

It was a great point gained, the Church's authority to dress as a man. Oh yes, wave on wave the good luck came sweeping in. Never mind about the smaller waves, let us come to the Largest one of all, the wave that swept us small fry quite off our feet and almost drowned us with joy. The day of the great verdict, couriers had been despatched to the King

with it, and the next morning bright and early the clear notes of a bugle came floating to us on the crisp air, and we pricked up our ears and began to count them. One—two—three; pause; one—two; pause; one—two—three, again—and out we skipped and went flying; for that formula was used only when the King's herald- at-arms would deliver a proclamation to the people. As we hurried along, people came racing out of every street and house and alley, men, women, and children, all flushed, excited, and throwing lacking articles of clothing on as they ran; still those clear notes pealed out, and still the rush of people increased till the whole town was abroad and streaming along the principal street. At last we reached the square, which was now packed with citizens, and there, high on the pedestal of the great cross, we saw the herald in his brilliant costume, with his servitors about him. The next moment he began his delivery in the powerful voice proper to his office:

'Know all men, and take heed therefore, that the most high, the most illustrious Charles, by the grace of God King of France, hath been pleased to confer upon his well-beloved servant Joan of Arc, called the Maid, the title, emoluments, authorities, and dignity of General-in-Chief of the Armies of France—'

Here a thousand caps flew into the air, and the multitude burst into a hurricane of cheers that raged and raged till it seemed as if it would never come to an end; but at last it did; then the herald went on and finished:

—'and hath appointed to be her lieutenant and chief of staff a prince of his royal house, his grace the Duke of Alencon!'

That was the end, and the hurricane began again, and was split up into innumerable strips by the blowers of it and wafted through all the lanes and streets of the town.

General of the Armies of France, with a prince of the blood for subordinate! Yesterday she was nothing—to-day she was this. Yesterday she was not even a sergeant, not even a corporal, not even a private—to-day, with one step, she was at the top.

Yesterday she was less than nobody to the newest recruit—today her command was law to La Hire, Saintrailles, the Bastard of Orleans, and all those others, veterans of old renown, illustrious masters of the trade of war. These were the thoughts I was thinking; I was trying to realise this strange and wonderful thing that had happened, you see.

My mind went travelling back, and presently lighted upon a picture—a picture which was still so new and fresh in my memory that it seemed a matter of only yesterday—and indeed its date was no further back than the first days of January. This is what it was. A peasant girl in a far-off village, her seventeenth year not yet quite completed, and herself and her village as unknown as if they had been on the other side of the globe. She had picked up a friendless wanderer somewhere and brought it home—a small grey kitten in a forlorn and starving condition— and had fed it and comforted it and got its confidence and made it believe in her, and now it was curled up in her lap asleep, and she was knitting a coarse stocking and thinking— dreaming—about what, one may never know. And now—the kitten had hardly had time to become a cat, and yet already the girl is General of the Armies of France, with a prince of the blood to give orders to, and out of her village obscurity her name has climbed up like the sun and is visible from all corners of the land! It made me dizzy to think of these things, they were so out of the common order, and seemed so impossible.

Joan's first official act was to dictate a letter to the English commanders at Orleans, summoning them to deliver up all Strongholds in their possession and depart out of France. She must have been thinking it all out before and arranging it in her mind, it flowed from her lips so smoothly, and framed itself into such vivacious and forcible language. Still, it might not have been so; she always had a quick mind and a capable tongue, and her faculties were constantly developing in these latter

weeks. This letter was to be forwarded presently from Blois. Men, provisions, and money were offering in plenty now, and Joan appointed Blois as a recruiting station and depot of supplies, and ordered up La Hire from the front to take charge.

The Great Bastard—him of the ducal house, and governor of Orleans—had been clamouring for weeks for Joan to be sent to him, and now came another messenger, old D'Aulon, a veteran officer, a trusty man and fine and honest. The King kept him, and gave him to Joan to be chief of her household, and commanded her to appoint the rest of her people herself, making their number and dignity accord with the greatness of her office; and at the same time he gave order that they should be properly equipped with arms, clothing, and horses.

Meantime the King was having a complete suit of armour made for her at Tours. It was of the finest steel, heavily plated with silver, richly ornamented with engraved designs, and polished like a mirror.

Joan's Voices had told her that there was an ancient sword hidden somewhere behind the altar of St. Catherine's at Fierbois, and she sent De Metz to get it. The priests knew of no such sword, but a search was made, and sure enough it was found in that place, buried a little way under the ground. It had no sheath and was very rusty, but the priests polished it up and sent it to Tours, whither we were now to come. They also had a sheath of crimson velvet made for it, and the people of Tours equipped it with another one, made of cloth of gold. But Joan meant to carry this sword always in battle; so she laid the showy sheaths away and got one made of leather. It was generally believed that this sword had belonged to Charle- magne, but that was only a matter of opinion. I wanted to sharpen that old blade, but she said it was not necessary, as she should never kill anybody, and should carry it only as a symbol of authority.

At Tours she designed her Standard, and a Scotch painter named James Power made it. It was of the most delicate white

boucassin, with fringes of silk. For device it bore the image of God the Father throned in the clouds and holding the world in His hand; two angels knelt at His feet, presenting lilies; inscription, Jesus, Maria; on the reverse the crown of France supported by two angels. She also caused a smaller standard or pennon to be made, whereon was represented an angel offering a lily to the Holy Virgin.

(Joan then goes to Blois where there is a big camp for the army. The camp is very disorderly, with soldiers roaming about, drinking and playing. There she meets La Hire, a rugged, tough, seasoned general, master of the camp, and orders him to set things right, impose proper discipline and, to his incredulity and dismay, make the troops attend holy services every day. He first argues against the latter command but must yield to Joan's insistence...)

In three days it was a clean camp and orderly, and those barbarians were herding to divine service twice a day like good children. The women were gone. La Hire was stunned by these marvels; he could not understand them. He went outside the camp when he wanted to swear. He was that sort of a man—sinful by nature and habit, but full of superstitious respect for holy places.

The enthusiasm of the reformed army for Joan, its devotion to her, and the hot desire she had aroused in it to be led against the enemy, exceeded any manifestations of this sort which La Hire had ever seen before in his long career. His admiration of it all, and his wonder over the mystery and miracle of it, were beyond his power to put into words. He had held this army cheap before, but his pride and confidence in it knew no limits now. He said:

'Two or three days ago it was afraid of a hen-roost; one could storm the gates of hell with it now.'

Joan and he were inseparable, and a quaint and pleasant contrast they made. He was so big, she so little; he was so grey and so far along in his pilgrimage of life, she so youthful; his face was so bronzed and scarred, hers so fair and pink, so fresh and smooth; she was so gracious, and he so stern; she was so pure, so innocent, he such a cyclopaedia of sin. In her eye was stored all charity and compassion, in his, lightnings; when her glance fell upon you it seemed to bring benediction and the peace of God, but with his it was different generally.

They rode through the camp a dozen times a day, visiting every corner of it, observing, inspecting, perfecting; and wherever they appeared, the enthusiasm broke forth. They rode side by side, he a great figure of brawn and muscle, she a little master- work of roundness and grace; he a fortress of rusty iron, she a shining statuette of silver; and when the reformed raiders and bandits caught sight of them they spoke out, with affection and welcome in their voices, and said:

'There they come — Satan and the Page of Christ!'

All the three days that we were in Blois, Joan worked earnestly and tirelessly to bring La Hire to God—to rescue him from the bondage of sin—to breathe into his stormy heart the serenity and peace of religion. She urged, she begged, she implored him to pray. He stood out, the three days of our stay, begging almost piteously to be let off—to be let off from just that one thing, that impossible thing; he would do anything else—anything—command, and he would obey—he would go through the fire for her, if she said the word—but spare him this, only this, for he couldn't pray, had never prayed, he was ignorant of how to frame a prayer, he had no words to put it in.

And yet—can any believe it?—she carried even that point, she won that incredible victory. She made La Hire pray. It shows, I think, that nothing was impossible to Joan of Arc. Yes, he stood there before her and put up his mailed hands and made a prayer. And it was not borrowed, but was his very own; he had none to help him frame it, he made it out of his own

head—saying:

'Fair Sir God, I pray you to do by La Hire as he would do by you if you were La Hire and he were God.'*

Then he put on his helmet and marched out of Joan's tent as satisfied with himself as any one might be who has arranged a perplexed and difficult business to the content and admiration of all the parties concerned in the matter.

If I had known that he had been praying, I could have understood why he was feeling so superior, but of course I could not know that.

I was coming to the tent at that moment, and saw him come out, and saw him march away in that large fashion, indeed it was fine and beautiful to see. But when I got to the tent door I stopped and stepped back, grieved and shocked, for I heard Joan crying, as I mistakenly, thought—crying as if she could not contain nor endure the anguish of her soul, crying as if she would die. But it was not so, she was laughing—laughing at La Hire's prayer.

It was not until six-and-thirty years afterwards that I found that out, and then—oh, then I only cried when that picture of young care-free mirth rose before me out of the blur and mists of that long-vanished time; for there had come a day between, when God's good gift of laughter had gone out from me to come again no more in this life.

***

We marched out in great strength and splendour, and took the road toward Orleans. The initial part of Joan's great dream was realising itself at last. It was the first time that any of us

------------------------------

*This prayer has been stolen many times and by many nations in the past four hundred and sixty years, but it originated with La Hire, and the fact is of official record in the National Archives of France. We have the authority of Michelet for this.—Translator.

youngsters had ever seen an army, and it was a most stately and imposing spectacle to us. It was indeed an inspiring sight, that interminable column, stretching away into the fading distances, and curving itself in and out of the crookedness of the road like a mighty serpent. Joan rode at the head of it with her personal staff; then came a body of priests singing the Veni Creator, the banner of the Cross rising out of their midst; after these the glinting forest of spears. The several divisions were commanded by the great Armagnac generals, La Hire, the Marshal de Boussac, the Sire de Retz, Florent d'llliers, and Poton de Saintrailles.

Each in his degree was tough, and there were three degrees— tough, tougher, toughest—and La Hire was the last by a shade, but only a shade. They were just illustrious official brigands, the whole party; and by long habits of lawlessness they had lost all acquaintanceship with obedience, if they had ever had any.

The King's strict orders to them had been, 'Obey the General- in-Chief in everything; attempt nothing without her knowledge, do nothing without her command.'

But what was the good of saying that? These independent birds knew no law. They Seldom obeyed the King; they never obeyed him when it didn't suit them to do it. Would they obey the Maid? In the first place they wouldn't know how to obey her or anybody else, and in the second place it was of course not possible for them to take her military character seriously— that country girl of seventeen who had been trained for the complex and terrible business of war—how? By tending sheep.

They had no idea of obeying her except in cases where their veteran military knowledge and experience showed them that the thing she required was sound and right when gauged by the regular military standards. Were they to blame for this attitude? I should think not. Old war worn captains are hard- headed, practical men. They do not easily believe in the ability of ignorant children to plan campaigns and command armies. No general that ever lived could have taken Joan seriously (militarily) before she raised the siege of Orleans and followed

Joan of Arc at Orleans by Jules-Eugene Lenepveu (1819-1898)

it with the great campaign of the Loire.

Did they consider Joan valueless? Far from it. They valued her as the fruitful earth values the sun—they fully believed she could produce the crop, but that it was in their line of business, not hers, to take it off. They had a deep and superstitious reverence for her as being endowed with a mysterious supernatural something that was able to do a mighty thing which they were powerless to do—blow the breath of life and valour into the dead corpses of cowed armies and turn them into heroes.

To their minds they were everything with her, but nothing without her. She could inspire the soldiers and fit them for battle—but fight the battle herself? Oh, nonsense—that was their function. They, the generals, would fight the battles, Joan would give the victory. That was their idea—an unconscious paraphrase of Joan's reply to the Dominican.

So they began by playing a deception upon her. She had a clear idea of how she meant to proceed. It was her purpose to march boldly upon Orleans by the north bank of the Loire. She gave that order to her generals. They said to themselves, 'The idea is insane—it is blunder No. 1; it is what might have been expected of this child who is ignorant of war.' They privately sent the word to the Bastard of Orleans. He also recognised the insanity of it—at least he thought he did—and privately advised the generals to get around the order in some way.

They did it by deceiving Joan. She trusted those people, she was not expecting this sort of treatment, and was not on the look-out for it. It was a lesson to her; she saw to it that the game was not played a second time.

Why was Joan's idea insane, from the generals' point of view, but not from hers? Because her plan was to raise the siege immediately, by fighting, while theirs was to besiege the besiegers and starve them out by closing their communications —a plan which would require months in the consummation.

The English had built a fence of strong fortresses called bastilles

around Orleans—fortresses which closed all the gates of the city but one. To the French generals the idea of trying to fight their way past those fortresses and lead the army into Orleans was preposterous; they believed that the result would be the army's destruction. One may not doubt that their opinion was militarily sound—no, would have been, but for one circumstance which they overlooked. That was this: the English soldiers were in a demoralised condition of superstitious terror; they had become satisfied that the Maid was in league with Satan. By reason of this a good deal of their courage had oozed out and vanished. On the other hand the Maid's soldiers were full of courage, enthusiasm, and zeal.

Joan could have marched by the English forts. However, it was not to be. She had been cheated out of her first chance to strike a heavy blow for her country.

In camp that night she slept in her armour on the ground. It was a cold night, and she was nearly as stiff as her armour itself when we resumed the march in the morning, for iron is not good material for a blanket. However, her joy in being now so far on her way to the theatre of her mission was fire enough to warm her, and it soon did it.

Her enthusiasm and impatience rose higher and higher with every mile of progress; but at last we reached Olivet, and down it went, and indignation took its place. For she saw the trick that had been played upon her—the river lay between us and Orleans.

She was for attacking one of the three bastilles that were on our side of the river and forcing access to the bridge which it guarded (a project which, if successful, would raise the siege instantly), but the long-ingrained fear of the English came upon her generals, and they implored her not to make the attempt. The soldiers wanted to attack, but had to suffer disappointment. So we moved on and came to a halt at a point opposite Checy, six miles above Orleans.

Dunois, Bastard of Orleans, with a body of knights and citizens came up from the city to welcome Joan. Joan was still

burning with resentment over the trick that had been put upon her, and was not in the mood for soft speeches, even to revered military idols of her childhood. She said:

'Are you the Bastard of Orleans?'

'Yes, I am he, and am right glad of your coming,'

'And did you advise that I be brought by this side of the river instead of straight to Talbot and the English?'

Her high manner abashed him, and he was not able to answer with anything like a confident promptness, but with many hesitations and partial excuses he managed to get out the confession that for what he and the council had regarded as imperative military reasons they had so advised.

'In God's name,' said Joan, 'my Lord's counsel is safer and wiser than yours. You thought to deceive me, but you have deceived yourselves, for I bring you the best help that ever knight or city had; for it is God's help, not sent for love of me, but by God's pleasure. At the prayer of St. Louis and St. Charlemagne He has had pity on Orleans, and will not suffer the enemy to have both the Duke of Orleans and his city. The provisions to save the starving people are here, the boats are below the city, the wind is contrary, they cannot come up hither. Now then tell me, in God's name, you who are so wise, what that council of yours was thinking about, to invent this foolish difficulty.'

Dunois and the rest fumbled around the matter a moment, then gave in and conceded that a blunder had been made.

'Yes, a blunder has been made,' said Joan, 'and except God take your proper work upon Himself and change the wind and correct your blunder for you, there is none else that can devise a remedy.'

Some of those people began to perceive that with all her technical ignorance she had practical good sense, and that with all her native sweetness and charm she was not the right kind of a person to play with.

Presently God did take the blunder in hand, and by His grace the wind did change. So the fleet of boats came up and

went away loaded with provisions and cattle, and conveyed that welcome succour to the hungry city, managing the matter successfully under protection of a sortie from the walls against the bastille of St. Loup. Then Joan began on the Bastard again:

'You see here the army?'

'Yes.'

'It is here on this side by advice of your council?'

'Yes.'

'Now, in God's name, can that wise council explain why it is better to have it here than it would be to have it in the bottom of the sea?'

Dunois made some wandering attempts to explain the inexplicable and excuse the inexcusable, but Joan cut him short and said—

'Answer me this, good sir—has the army any value on this side of the river?'

The Bastard confessed that it hadn't—that is, in view of the plan of campaign which she had devised and decreed.

And yet, knowing this, you had the hardihood to disobey my orders. Since the army's place is on the other side, will you explain to me how it is to get there?'

The whole size of the needless muddle was apparent. Evasions were of no use; therefore Dunois admitted that there was no way to correct the blunder but to send the army all the way back to Blois, and let it begin over again and come up on the other side this time, according to Joan's original plan.

Any other girl, after winning such a triumph as this over a veteran soldier of old renown, might have exulted a little and been excusable for it, but Joan showed no disposition of this sort. She dropped a word or two of grief over the precious time that must be lost, then began at once to issue commands for the march back. She sorrowed to see her army go; for she said its heart was great and its enthusiasm high, and that with it at her back she did not fear to face all the might of England.

All arrangements having been completed for the return of the main body of the army, she took the Bastard and La Hire and a

thousand men and went down to Orleans, where all the town was in a fever of impatience to have sight of her face. It was eight in the evening when she and the troops rode in at the Burgundy gate, with the Paladin preceding her with her standard. She was riding a white horse and she carried in her hand the sacred sword of Fierbois. You should have seen Orleans then. What a picture it was! Such black seas of people, such a starry firmament of torches, such roaring whirlwinds of welcome, such booming of bells and thundering of cannon! It was as if the world was come to an end. Everywhere in the glare of the torches one saw rank upon rank of upturned white faces, the mouths wide open, shouting, and the unchecked tears running down; Joan forged her slow way through the solid masses, her mailed form projecting above the pavement of heads like a silver statue. The people about her struggled along, gazing up at her through their tears with the rapt look of men and women who believe they are seeing one who is divine; and always her feet were being kissed by grateful folk, and such as failed of that privilege touched her horse and then kissed their fingers.

Nothing that Joan did escaped notice; everything she did was commented upon and applauded. You could hear the remarks going all the time.

'There—she's smiling—see!'

'Now she's taking her little plumed cap off to somebody— ah, it's fine and graceful!'

'She's patting that woman on the head with her gauntlet.'

'Oh, she was born on a horse—see her turn in her saddle, and kiss the hilt of her sword to the ladies in the window that threw the flowers down.'

'Now there's a poor woman lifting up a child—she's kissed it—oh, she's divine!'

'What a dainty little figure it is, and what a lovely face—and such colour and animation!'

Joan's slender long banner streaming backward had an accident —the fringe caught fire from a torch. She leaned forward and crushed the flame in her hand.

'She's not afraid of fire nor anything!' they shouted, and delivered a storm of admiring applause that made everything quake.

She rode to the cathedral and gave thanks to God, and the people crammed the place and added their devotions to hers;

then she took up her march again and picked her slow way through the crowds and the wilderness of torches to the house of Jacques Boucher, treasurer of the Duke of Orleans, where she was to be the guest of his wife as long as she stayed in the city, and have his young daughter for comrade and room-mate. The delirium of the people went on the rest of the night, and with it the clamour of the joy-bells and the welcoming cannon.

Joan of Arc had stepped upon her stage at last, and was ready to begin.

***

She was ready, but must sit down and wait until there was an army to work with.

Next morning, Saturday, April 30, 1429, she set about inquiring after the messenger who carried her proclamation to the English from Blois—the one which she had dictated at Poitiers. Here is a copy of it. It is a remarkable document, for several reasons: for its matter-of-fact directness, for its high spirit and forcible diction, and for its naive confidence in her ability to achieve the prodigious task which she had laid upon herself, or which had been laid upon her—which you please. All through it you seem to see the pomps of war and hear the rumbling of the drums. In it Joan's warrior soul is revealed, and for the moment the soft little shepherdess has disappeared from your view. This untaught country damsel, unused to dictating anything at all to anybody, much less documents of state to kings and generals, poured out this procession of vigorous sentences as fluently as if this sort of work had been her trade from childhood:

JESUS MARIA

'King of England, and you Duke of Bedford who call yourself Regent of France; William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk; and you Thomas Lord Scales, who style yourselves lieutenants of the said Bedford— do right to the King of Heaven. Render to the Maid who is sent by God the keys of all the good towns you have taken and violated in France. She is sent hither by God to restore the blood royal. She is very ready to make peace if you will do her right by giving up France and paying for what you have held. And you archers, companions of war, noble and otherwise, who are before the good city of Orleans, begone into your own land in God's name, or expect news from the Maid who will shortly go to see you to your very great hurt. King of England, if you do not so, I am chief of war, and wherever I shall find your people in France I will drive them out, willing or not willing; and if they do not obey I will slay them all, but if they obey, I will have them to mercy. I am come hither by God, the King of Heaven, body for body, to put you out of France, in spite of those who would work treason and mischief against the kingdom. Think not you shall ever hold the kingdom from the King of Heaven, the Son of the Blessed Mary; King Charles shall hold it, for God wills it so, and has revealed it to him by the Maid. If you believe not the news sent by God through the Maid, wherever we shall meet you we will strike boldly and make such a noise as has not been in France these thousand years. Be sure that God can send more strength to the Maid than you can bring to any assault against her and her good men-at-arms; and then we shall

see who has the better right, the King of Heaven, or you. Duke of Bedford, the Maid prays you not to bring about your own destruction. If you do her right, you may yet go in her company where the French shall do the finest deed that has ever been done in Christendom, and if you do not, you shall be reminded shortly of your great wrongs.'

In that closing sentence she invites them to go on crusade with her to rescue the Holy Sepulchre.

No answer had been returned to this proclamation, and the messenger himself had not come back. So now she sent her two heralds with a new letter warning the English to raise the siege and requiring them to restore that missing messenger. The heralds came back without him. All they brought was notice from the English to Joan that they would presently catch her and burn her if she did not clear out now while she had a chance, and 'go back to her proper trade of minding cows.'

She held her peace, only saying it was a pity that the English would persist in inviting present disaster and eventual destruction when she was 'doing all she could to get them out of the country with their lives still in their bodies.'

Presently she thought of an arrangement that might be acceptable, and said to the heralds, 'Go back and say to Lord Talbot this, from me: "Come out of your bastilles with your host, and I will come with mine; if I beat you, go in peace out of France; if you beat me, burn me, according to your desire."'

I did not hear this, but Dunois did, and spoke of it. The challenge was refused.

Sunday morning her Voices or some instinct gave her a warning, and she sent Dunois to Blois to take command of the army and hurry it to Orleans. It was a wise move, for he found Regnault de Chartres and some more of the King's pet rascals there trying their best to disperse the army, and crippling all the efforts of Joan's generals to head it for Orleans. They were a fine lot, those miscreants. They turned their attention to Dunois, now, but he had baulked Joan once, with unpleasant results

to himself, and was not minded to meddle in that way again. He soon had the army moving.

(During the waiting period near Orleans, Joan sees a soldier in chains. Upon enquiry, she learns that he is a deserter who has been sentenced to death and is awaiting execution. Questioning further, she is told that he left the army because his wife was dying but came back voluntarily despite being aware that his life was at risk. Joan decides to pardon him. His nickname is the Dwarf although he is about seven feet tall and very big. He wows allegiance to the person of Joan and becomes a kind of bodyguard for her. He will indeed be at her sides in all the battles.

Meanwhile, on both sides, everyone is waiting for the battle for Orleans to begin. Suddenly...)

About noon I was chatting with Madame Boucher; nothing was going on, all was quiet, when Catherine Boucher suddenly entered in great excitement, and said—

'Fly, sir, fly! The Maid was dozing in her chair in my room, when she sprang up and cried out, "French blood is flowing! —my arms, give me my arms!" Her giant was on guard at the door, and he brought D'Aulon, who began to arm her, and I and the giant have been warning the staff. Fly!—and stay by her; and if there really is a battle, keep her out of it—don't let her risk herself—there is no need—if the men know she is near and looking on, it is all that is necessary. Keep her out of the fight—don't fail of this!'

I started on a run, saying, sarcastically—for I was always fond of sarcasm, and it was said that I had a most neat gift that way-

'Oh yes, nothing easier than that—I'll attend to it!'

At the furthest end of the house I met Joan, fully armed, hurrying toward the door, and she said—

'Ah, French blood is being spilt, and you did not tell me.'

'Indeed I did not know it,' I said; 'there are no sounds of war; everything is quiet, your Excellency.'

'You will hear war-sounds enough in a moment,' she said, and was gone.

It was true. Before one could count five there broke upon the stillness the swelling rush and tramp of an approaching multitude of men and horses, with hoarse cries of command; and then out of the distance came the muffled deep boom!— boom-boom!—boom! of cannon, and straightway that rushing multitude was roaring by the house like a hurricane.

Our knights and all our staff came flying, armed, but with no horses ready, and we burst out after Joan in a body, the Paladin in the lead with the banner. The surging crowd was made up half of citizens and half of soldiers, and had no recognised leader. When Joan was seen a huzzah went up, and she shouted—

A horse—a horse!'

A dozen saddles were at her disposal in a moment. She mounted, a hundred people shouting—

'Way, there—way for the MAID OF ORLEANS!' The first time that that immortal name was ever uttered—and I, praise God, was there to hear it! The mass divided itself like the waters of the Red Sea, and down this lane Joan went skimming like a bird, crying 'Forward, French hearts—follow me!' and we came winging in her wake on the rest of the borrowed horses, the holy standard streaming above us, and the lane closing together in our rear.

This was a different thing from the ghastly march past the dismal bastilles. No, we felt fine, now, and all a-whirl with enthusiasm. The explanation of this sudden uprising was this. The city and the little garrison, so long hopeless and afraid, had gone wild over Joan's coming, and could no longer restrain their desire to get at the enemy; so, without orders from anybody, a few hundred soldiers and citizens had plunged out at

The armament of the horse at the time of Joan of Arc

Left: An archer at the time of Joan of Arc

Right : A crossbowman at the time of Joan of Arc

the Burgundy gate on a sudden impulse and made a charge on one of Lord Talbot's most formidable fortresses—St. Loup—and were getting the worst of it. The news of this had swept through the city and startled this new crowd that we were with.

As we poured out at the gate we met a force bringing in the wounded from the front. The sight moved Joan, and she said—

'Ah, French blood; it makes my hair rise to see it!'

We were soon on the field, soon in the midst of the turmoil. Joan was seeing her first real battle, and so were we.

It was a battle in the open field; for the garrison of St. Loup had sallied confidently out to meet the attack, being used to victories when 'witches' were not around. The sally had been re-enforced by troops from the 'Paris' bastille, and when we approached the French were getting whipped and were falling back. But when Joan came charging through the disorder with her banner displayed, crying 'Forward, men—follow me!' there was a change; the French turned about and surged forward like a solid wave of the sea, and swept the English before them, hacking and slashing, and being hacked and slashed, in a way that was terrible to see.

In the field the Dwarf had no assignment; that is to say, he was not under orders to occupy any particular place, therefore he chose his place for himself, and went ahead of Joan and made a road for her. It was horrible to see the iron helmets fly into fragments under his dreadful axe. He called it cracking nuts, and it looked like that. He made a good road, and paved it well with flesh and iron. Joan and the rest of us followed it so briskly that we outspeeded our forces and had the English behind us as well as before. The knights commanded us to face outwards around Joan, which we did, and then there was work done that was fine to see. One was obliged to respect the Paladin, now. Being right under Joan's exalting and transforming eye, he forgot his native prudence, he forgot his diffidence in the presence of danger, he forgot what fear was, and he never laid about him in his imaginary battles in a more tremendous way than he did in this real one; and wherever he

struck there was an enemy the less.

We were in that close place only a few minutes; then our forces to the rear broke through with a great shout and joined us, and then the English fought a retreating fight, but in a fine and gallant way, and we drove them to their fortress foot by foot, they facing us all the time, and their reserves on the walls raining showers of arrows, cross-bow bolts, and stone cannon- balls upon us.

The bulk of the enemy got safely within the works and left us outside with piles of French and English dead and wounded for company—a sickening sight, an awful sight to us youngsters, for our little ambush fights in February had been in the night, and the blood and the mutilations and the dead faces were mercifully dim, whereas we saw these thing's now for the first time in all their naked ghastliness.

Now arrived Dunois from the city, and plunged through the battle on his foam-flecked horse and galloped up to Joan, saluting, and uttering handsome compliments as he came. He waved his hand toward the distant walls of the city, where a multitude of flags were flaunting gaily in the wind, and said the populace were up there observing her fortunate performance and rejoicing over it, and added that she and the forces would have a great reception now.

'Now? Hardly now, Bastard. Not yet!' 'Why not yet? Is there more to be done?' 'More, Bastard? We have but begun! We will take this fortress.'

'Ah, you can't be serious! We can't take this place; let me urge you not to make the attempt; it is too desperate. Let me order the forces back.'

Joan's heart was overflowing with the joys and enthusiasms of war, and it made her impatient to hear such talk. She cried out-

'Bastard, Bastard, will ye play always with these English? Now verily I tell you we will not budge until this place is ours. We will carry it by storm. Sound the charge!'

'Ah, my General—'

'Waste no more time, man—let the bugles sound the assault!' and we saw that strange deep light in her eye which we named the battle-light, and learned to know so well in later fields.

The martial notes pealed out, the troops answered with a yell, and down they came against that formidable work, whose outlines were lost in its own cannon smoke, and whose sides were spouting flame and thunder.

We suffered repulse after repulse, but Joan was here and there and everywhere encouraging the men, and she kept them to their work. During three hours the tide ebbed and flowed, flowed and ebbed; but at last La Hire, who was now come, made a final and resistless charge, and the bastille St. Loup was ours. We gutted it, taking all its stores and artillery, and then destroyed it.

When all our host was shouting itself hoarse with rejoicings, and there went up a cry for the General, for they wanted to praise her and glorify her and do her homage for her victory, we had trouble to find her; and when we did find her, she was off by herself, sitting among a ruck of corpses, with her face in her hands, crying—for she was a young girl, you know, and her hero-heart was a young girl's heart too, with the pity and the tenderness that are natural to it. She was thinking of the mothers of those dead friends and enemies.

Among the prisoners were a number of priests, and Joan took these under her protection and saved their lives. It was urged that they were most probably combatants in disguise, but she said—

'As to that, how can any tell? They wear the livery of God, and if even one of these wears it rightfully, surely it were better that all the guilty should escape than that we have upon our hands the blood of that innocent man. I will lodge them where I lodge, and feed them, and send them away in safety.'

We marched back to the city with our crop of cannon and prisoners on view and our banners displayed. Here was the first substantial bit of war-work the imprisoned people had seen in the seven months that the siege had endured, the first

chance they had had to rejoice over a French exploit. You rnay guess that they made good use of it. They and the bells went mad Joan was their darling now, and the press of people struggling and shouldering each other to get a glimpse of her was so great that we could hardly push our way through the streets at all. Her new name had gone all about, and was on everybody's lips. The Holy Maid of Vaucouleurs was a forgotten title; the city had claimed her for its own, and she was the MAID OF ORLEANS now. It is a happiness to me to remember that I heard that name the first time it was ever uttered. Between that first utterance and the last time it will be uttered on this earth—ah, think how many mouldering ages will lie in that gap!

The Boucher family welcomed her back as if she had been a child of the house, and saved from death against all hope or probability. They chided her for going into the battle and exposing herself to danger during all those hours. They could not realise that she had meant to carry her warriorship so far, and asked her if it had really been her purpose to go right into the turmoil of the fight, or hadn't she got swept into it by accident and the rush of the troops? They begged her to be more careful another time. It was good advice, maybe, but it fell upon pretty unfruitful soil.

***

(...) The next day Joan wanted to go against the enemy again, but it was the feast of the Ascension, and the holy council of bandit generals were too pious to be willing to profane it with bloodshed. But privately they profaned it with plottings, a sort of industry just in their line. They decided to do the only thing proper to do now in the new circumstance of the case—feign an attack on the most important bastille on the Orleans side, and then, if the English weakened the far more important fortresses on the other side of the river to come to its help, cross in force and capture those works. This would give them the

bridge and free communication with the Sologne, which was French territory They decided to keep this latter part of the programme secret from Joan.

Joan intruded and took them by surprise. She asked them what they were about and what they had resolved upon. They said they had resolved to attack the most important of the English bastilles on the Orleans side next morning—and there the spokesman stopped. Joan said—

'Well, go on.'

'There is nothing more. That is all.'

'Am I to believe this? That is to say, am I to believe that you have lost your wits?' She turned to Dunois, and said, 'Bastard, you have sense, answer me this: if this attack is made and the bastille taken, how much better off would we be than we are now?'

The Bastard hesitated, and then began some rambling talk not quite germane to the question. Joan interrupted him and said—

'That will do, good Bastard, you have answered. Since the Bastard is not able to mention any advantage to be gained by taking that bastille and stopping there, it is not likely that any of you could better the matter. You waste much time here in inventing plans that lead to nothing, and making delays that are a damage. Are you concealing something from me? Bastard, this council has a general plan, I take it; without going into details, what is it?'

'It is the same it was in the beginning, seven months ago— to get provisions in for a long siege, and then sit down and tire the English out.'

'In the name of God! As if seven months was not enough,

you want to provide for a year of it. Now ye shall drop these pusillanimous dreams—the English shall go in three days!'

Several exclaimed—

'Ah, General, General, be prudent!'

'Be prudent and starve? Do ye call that war? I tell you this, if you do not already know it: The new circumstances have

changed the face of matters. The true point of attack has shifted; it is on the other side of the river now. One must take the fortifications that command the bridge. The English know that if we are not fools and cowards we will try to do that. They are grateful for your piety in wasting this day. They will re-enforce the bridge forts from this side to-night, knowing what ought to happen to-morrow. You have but lost a day and made our task harder, for we will cross and take the bridge forts. Bastard, tell me the truth—does not this council know that there is no other course for us than the one I am speaking of?'

Dunois conceded that the council did know it to be the most desirable, but considered it impracticable; and he excused the council as well as he could by saying that inasmuch as nothing was really and rationally to be hoped for but a long continuance of the siege and wearying out of the English, they were naturally a little afraid of Joan's impetuous notions. He said—

'You see, we are sure that the waiting game is the best, whereas you would carry everything by storm.'

'That I would!—and moreover that I will! You have my orders—here and now. We will move upon the forts of the south bank to-morrow at dawn.'

'And carry them by storm?'

'Yes, carry them by storm!'

La Hire came clanking in, and heard the last remark. He cried out—

'By my baton, that is the music I love to hear! Yes, that is the right tune and the beautiful words, my General—we will carry them by storm!'

He saluted in his large way and came up and shook Joan by the hand.

Some member of the council was heard to say—

'It follows, then, that we must begin with the bastille St. John, and that will give the English time to—'

Joan turned and said—

'Give yourselves no uneasiness about the bastille St. John. The English will know enough to retire from it and fall back on the bridge bastilles when they see us coming.' She added, with a touch of sarcasm, 'Even a war-council would know enough to do that, itself.'

Then she took her leave. La Hire made this general remark to the council:

'She is a child, and that is all ye seem to see. Keep to that superstition if you must, but you perceive that this child understands this complex game of war as well as any of you; and if you want my opinion without the trouble of asking for it, here you have it without ruffles or embroidery —by God, I think she can teach the best of you how to play it!'