Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist - The Story of Abraham Lincoln - Chapter IV

Chapter IV

Once Again

1864 Presidential elections were now less than a year away and as much as he disliked any stirring of the issue he could not ignore it anymore. Republican newspapers began speaking highly of many possible candidates — Seward, Fremont, Chase etc. in addition to appreciation of Lincoln. By November 1863, he had decided to contest again and declared that if his friends desired his renomination, he was agreeable to his candidacy.

Divergent views in the Republican Party began to come forward. Lincoln tried to pacify both factions of the party. He found himself caught in a very difficult situation — when he appeased the conservatives he upset the radicals who threatened to resign from the administration and when he agreed with radicals, conservatives would fume and complain. Lincoln was also opposed by another class on men; those with deep personal rivalries. Some resented that their advice was not heeded; others were dissatisfied that political favours were not returned.

In an effort to boost his chances of reelection he began

hosting social events at the White House through the winter. To keep an eye on the abolitionists' sentiment, Lincoln often invited Charles Sumner, a prominent abolitionist to the White House on personal visits; it would also prevent him from defecting to the opposition.

Within the republicans there was no discontent with Lincoln on ideological grounds; republicans like Salmon Chase, Horace Greeley and Benjamin Wade and others agreed on the need to fight the war till victorious, on the abolishment of slavery and the restoration of Southern states on fulfillment of certain conditions. In fact, in support of his Amnesty and Reconstruction proclamation, republicans worked hard to create laws to fulfill it. In keeping with his ideas, James Ashley introduced a bill for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery nationally, (to which he also added Negro franchise).

They hesitated only on grounds of his incapacity to arrive at the goals effectively. They found him a weak administrator who despite two and a half years of an expensive war and loss to life and property was unable to defeat the rebels a quarter in manpower compared to the North. A call for 500,000 men in March for the Union armies did not make things better.

It was a disconcerting observation but his supporters felt comfort in the predictions of newsmen who had declared that 'Mr. Lincoln has the confidence of the people, and even the respect and affection of the masses'1. Letters of appreciation by his supporters bolstered his spirit, especially words of support from the army,

`I believe it is God's purpose to end this war in the coming year and also his purpose to call Abraham Lincoln again to the Presidential Chair' .2

His supporters got to work immediately; they had to ensure his renomination by June when the republican convention would meet in Baltimore. His political workers mobilised support for Lincoln using Union Leagues all over the Northern States; they

- A. Lincoln: A Biography, By Ronald C. White, Jr., p. 614

- The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, James C. Rice to Henry Wilson, Wednesday, November 11, 1863, images 2&3

did not miss the opportunity at the New Hampshire republican convention, where his supporters pushed a resolution declaring Lincoln as the people's choice for reelection. Simon Cameron, Lincoln's former Secretary of War, grateful to him for bearing part of the blame for the blunders in the war department, took charge of getting the signatures of all Republican lawmakers of Pennsylvania on a request that Lincoln would allow his reelection. His supporters in the legislatures of several states declared their approval of his reelection. The New England Loyal Publication Society broke its rule against taking sides during elections and published a strong editorial prompting people that:

"A man's adaptation to an official place cannot be perfectly known until it is practically tested...it is no time to risk anything... Wise policy impels the loyal people ...to continue President Lincoln in his responsible position... and against the powerful will of the people, politicians are powerless"1

Lincoln had been trying hard since the issue of the emancipation proclamation to get Governors in federal occupied congressional districts of Southern states to push for reconstruction. While Lincoln pressed upon the military governors and generals to organize free state governments, he also advised them to:

"Follow forms of law as far as convenient, but at all times get the expression of the largest number of the people possible2... What we do want is the conclusive evidence that respectable citizens of Louisiana, are willing to be members of congress & to swear support to the constitution; and that other respectable citizens there are willing to vote for them and send therm To send a parcel of Northern men here, as representatives, elected as would

- https://repository.library.brown.eduiviewers/image/zoom/bdr:80343

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 5, To Ulysses S. Grant, Andrew Johnson and Others, Oct. 21, 1862, p. 470

be understood, (and perhaps really so,) at the point of the bayonet, would be disgusting and outrageous"1

However, news of the formation of free governments under Lincoln's ten percent plan in Arkansas, Tennessee and Louisiana2 was not received well by the radicals, who denounced them and hoped to get a resolution passed in Congress to ensure that the eleven seceded states were not entitled to representation in the electoral colleges during the forthcoming presidential elections.

Lincoln's party members opposed him on other grounds as well. Republican congressmen were critical of the power the executive branch had assumed during the war at the expense of the legislative branch. They felt that reconstruction ought to be a subject under Congressional control, not executive. By issuing the proclamation of amnesty and reconstruction, Lincoln had declared it as a subject under executive control.

Secondly, state governments in Southern states with ten percent representation of voters in Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee and North Carolina would earn Lincoln enough electoral votes needed to win the presidential election. Lincoln looked forward to their support but that was not the sole reason for his wanting their organization. He genuinely wanted the people of the states to abolish slavery and form their own government. Already peeved with his use of his war powers, the radicals resented the advantage he would have during the elections with the support

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), To George F. Shepley, Nov 21st 1862, page 384

- In February 1864, when the free state government in Louisiana was formed without calling a convention to draw up a new constitution for the state, it was criticised by most republicans. General Banks, in a hurry to set up a free government adopted the old constitution by merely declaring provisions relating to slavery as null and void. This left the state vulnerable to a reversal in case the pro slavery party got control. Radical and conservative republicans were both critical of these developments. Though Lincoln was pleased with the formation of the free state government in Louisiana, he felt badly about the defenselessness of the newly freed blacks and suggested to the new governor of Louisiana if 'some of the colored people...for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks' should be permitted to vote.

of these new governments. Lashing out at Lincoln's endeavor to organize free state governments in Southern states that were ruled by the despotic military laws, and objecting to Lincoln's weak plan for reconstruction, a bill was introduced by radical republican Henry Winter Davis with the assistance of Benjamin Wade, Charles Sumner and other prominent radicals in Congress in February 1864. In contrast to Lincoln's ten percent plan, it mainly declared that any state wanting readmission into the union would have to abolish slavery, 50 percent of its 1860 voters would have to take part in elections to form their government and that electors of state conventions had to take an oath that they had not voluntarily taken up arms against the Unites States or helped the rebellion. This was in direct contrast to Lincoln's plan that required from those that did rebel, an oath of allegiance to the Union to not do so in the future.

Soon he found an opponent in his own backyard; Chase, Secretary of Treasury,1 with his passion for the presidential chair and supported by a belief that he was superior to Lincoln in his ability to lead the nation, had built up his own political support among the republicans. From as early as December 1863, his supporters with his tacit approval began to discuss strategies for Chase's campaign. In February 1864, they secretly began circulating pamphlets among the party members criticising Lincoln as weak and indecisive and demanding a candidate who was an `advanced thinker; a statesman profoundly versed in political and economic science, one who fully comprehends the spirit of the age'.2 It left no one in doubt as to whom the pamphlets were alluding to.

Lincoln seemed quite unperturbed about news of Chase's secret run for the nomination; by February, various Republican conventions had already declared support for Lincoln's reelection.

- Chase had been resentful of his humiliating position in the 1862 cabinet debacle and Lincoln's warm relationship with Seward irked him. He felt his efforts to keep the administration financially afloat during the war were not appreciated and Lincoln's decentralized administration policy did not allow him to exercise control over the disbursement of funds he so painstakingly made available.

- Republican Opinions about Lincoln, document no. 18, p. 4

Congressman Frank Blair attacked Chase on grounds of corruption in the War Department. In March, his supporters managed to expose his plan; not only was Chase forced to withdraw from the presidential race, he felt embarrassed enough to tender his resignation as secretary of treasury yet again. Shrewdly, Lincoln kept him waiting for a few months and then, much to the astonishment of his colleagues, refused to accept his resignation; with his renomination still uncertain, Chase was less harmful in the cabinet than outside it, he explained.

Radicals, still looking for an alternative to Lincoln, suggested the name of General Grant; he had been successful in his campaigns and would be a popular candidate as a president who could lead the union safely and swiftly through the war. However, Grant, having no political ambitions, refused; his loyalty to Lincoln would not allow him to accept the nomination. But by May most states fell into line in support of Lincoln for renomination; Western states were stronger in their support but despite resistance from Radicals, Eastern states also came through.

In the midst of all these developments, Lincoln had been looking for the right military general to lead the Union to final victory and bring the war to a close. In comparison to his lethargic generals in the Eastern theatre, those in the West were far more energetic and successful. He found in General Grant the capacity of motivating the troops into striding towards ultimate success. In March 1864, Lincoln promoted him to lieutenant general in charge of all Union armies. Leaving the Western armies under the command of General Sherman, Grant went to Virginia to take command of the army of the Potomac.

Grant, after much deliberation came up with the Overland Campaign, a plan to launch concurrent massive attacks in Virginia that would wear out the confederates and destroy them; General Butler would go towards Richmond to capture the confederate capital, General Meade, commanding the army of the Potomac would cross the Rapidan River into the wilderness of Northern Virginia to attack Lee and General Sigel would go south to capture railroad lines at Lynchburg, Virginia. Simultaneously, Grant

ordered General Sherman to lead the armies of the West to capture Atlanta, an important supply centre and railroad hub for the confederates. Lincoln was pleased with Grant's plan; finally he had found a general who shared his belief — to win the war it was imperative to destroy the confederate army.

With the election fever mounting, in May 1864, a faction of Republicans met at Cleveland and denounced the Lincoln administration for its weak and ineffective war policy. Most of the delegates were German Americans, mainly from Missouri where they hated Lincoln and were extremely devoted to John C. Fremont and a body of ultra-radicals abolitionists from the Northeast. They formed the Radical Democracy Party and nominated John C. Fremont, as their candidate for presidency, adopting a platform calling for a constitutional amendment prohibiting slavery and complete racial equality enforceable by law. It also backed direct presidential elections, single term for presidency, free speech, free press, habeas corpus and confiscation of rebel lands. Notable republicans like Horace Greeley stayed away after knowing that the majority was backing Fremont.

The Radicals in their platform had included constitutional amendment abolishing slavery and complete racial equality that included Negro franchise; Lincoln knew that the country was not ready for such an extreme measure. Before the republican convention met in June, he invited Senator Edwin D. Morgan of New York, to the White House, and asked him to include an amendment of the Constitution abolishing and prohibiting slavery forever as the substance of his opening speech and as the focal point in the party platform. This, he hoped, would win the dissidents back into their fold.

The Republican Convention that met at Baltimore in June was entirely controlled by Lincoln's supporters. It was attended by various factions — radicals like Thaddeus Stevens, delegates from States undergoing reconstruction under Lincoln's ten percent plan; Claybanks (conservatives) and Charcoals (radical) delegates from Missouri; it was also attended by some War Democrats. Decision had been taken to rename the convention

as the National Union Party convention to avoid divisive factional issues erupting among the Republicans. The National Union Party, renamed thus, was also a means to attract War Democrats from the Border States who believed in Lincoln's war policies but would not have voted for the Republican Party.

Their party platform called for an amendment to the constitution to terminate and forever prohibit the existence of slavery in the entire nation. Other issues in the platform were pursuit of war until complete confederate surrender, aid to disabled union veterans, continued European neutrality, enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, appreciation of the emancipation proclamation and Negro enlistment, encouragement of immigration and the building of a transcontinental railroad. Lincoln was unanimously renominated as the Presidential candidate. Andrew Jackson, a War Democrat from the South was nominated as his running mate for Vice President; a clever choice as it symbolized a wider coalition and reflected the inclusiveness of all states in the union.

The party platform was immensely cheered by the masses and received rave reviews from the press:

"...The Proclamation of Emancipation and the use of negro troops... it is a proper and efficient means of weakening the rebellion which every person desiring its speedy overthrow must zealously and perforce uphold... let the Proclamation go wherever the army goes... and let it summon to our aid the negroes who are truer to the Union than their disloyal masters... let us protect and defend them... Is there anything unconstitutional in that? ...And he who is willing to give back to slavery a single person... is not worthy the name of American..."1

1. The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812 & the Civil War, by Joseph T. Wilson, p. 107

Lincoln In Charge

With the renomination assured, Lincoln could now deal strongly with his cabinet and his party. He had already decided to relieve Chase from the post of Secretary of Treasury; he was waiting for the right time. Uncomfortable with each other during cabinet meetings, Chase himself presented the opportunity by tendering his resignation yet again. Chase, sure that it would once again be refused, was taken aback when Lincoln accepted it without demur and swiftly nominated William Fessenden as his secretary of the treasury. Satisfied with the reorganization of his cabinet, he now decided to assert his leadership in political issues.

Radicals, in an effort to assert congressional instead of the executive control over the process of reconstruction and to oppose Lincoln's 10 percent plan for reconstruction, which they found too weak, had introduced the Wade-Davis bill in February. Lincoln found the language of the bill stating that the Southern states need to 'rejoin' the union to be in direct conflict with the republican rationale that the war was being fought 'within the union' to quell a rebellion. Secondly, Lincoln believed that Congress had no right to compel states to form constitutions abolishing slavery as the present constitution stated that slavery was a state issue. Moreover, Lincoln found it too severe; he wanted that the Southern states should be cajoled back into a harmonious coexistence instead of being treated like traitors who ought to be punished. With great difficulty Lincoln had managed to create a coalition between the War Democrats and Republicans to support his reelection; the Wade-Davis bill would shatter it. Emancipation movements that were beginning to take off in the Border States would be jeopardized. Free governments set up on the basis of his 10 percent plan in Louisiana, Arkansas and Tennessee would get nullified. By 2nd July it had been passed by both houses and presented to the president for

his signature on the 4th. Lincoln decided to pocket veto1 the bill, protesting that 'this bill was placed before me a few minutes before Congress adjourns. It is a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way'2.

Despite the fact that the Radicals could do much damage to his reelection, he defended his action, `.../ must keep some consciousness of being somewhere near right. I must keep some standard of principle fixed within myself3.

To clarify his position before the public, within four days he issued a proclamation stating that he was not inclined to limit himself to a single plan of restoration, or willing to discourage the efforts of the people of Arkansas and Louisiana who had set up their free state governments, nor did he believe that Congress had the right to abolish slavery in states. In the end he endorsed the bill as being satisfactory for those who wished to adopt it offering assistance to those who would.

The Mighty Scourge Of War

After much thought and preparation, Grant's Overland Campaign finally took off in May 1864. The confederates defeated Sigel, and Butler found himself surrounded by the enemy near Petersburg. The army of the Potomac combatted with Lee's forces for 40 odd days; of a 120,000 union men against Lee's force of 60,000, the union army fought four deadly battles and lost around 50,000 men to Lee's losses of 30,000. Casualty news in the North earned Grant the title of 'the Butcher'. Though

- Pocket veto - The Constitution grants the president 10 days to review a Bill passed by the Congress. If the president has not signed the bill after 10 days, it becomes law without his signature. However, if Congress adjourns during the 10-day period, the bill does not become law.

- Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, by John Hay, page 217

- Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald, page 511

Lincoln tried to keep himself busy with administrative matters, his people saw him walking up and down his office with 'his long arms behind his back, his dark features contracted still more with gloom'1. At times the relentless war overwhelmed him, 'Why do we suffer reverses after reverses! Could we have avoided this terrible, bloody war! ... Is it ever to end!'2 Though extremely devastated by the news of repeated setbacks, Lincoln tried not to get demoralized; Grant had reassured Lincoln, 'I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.'3 He was different from his other Generals of the Eastern Theatre; he managed with as many men he had and he did not withdraw from battle like them, leaving the enemy to retort back for yet another battle. Despite the heavy losses, Lincoln had no choice but to support Grant; at this point this seemed the only way possible to arrive at victory. After four failed maneuvers, Grant pulled out of the last one at Cold Harbor, freed Butler and his men and attacked Petersburg, Richmond's central rail hub. Unable to capture the city, Grant finally settled to besiege the town of Petersburg in mid June. Pinned down to defend Petersburg, Lee would be unable to send reinforcements to fight against Sherman who was trying to capture Atlanta.

Daily newspaper columns carrying the names of the dead, swelling numbers in hospitals, hundreds of letters pouring out the horrors of war and the suffering of the maimed by soldiers and war correspondents outraged the country. Horace Greeley wrote to the president that the nation was dreading the probability of another conscription and the never-ending carnage of war.

Lincoln was deeply affected by the dismal sights he saw and heard of. One evening, riding past a train of ambulances he anguished, "'Look yonder at those poor fellows. I cannot bear it. This suffering, this loss of life is dreadful.' In an effort to pull him out of his misery, his friend said, 'do you remember writing to your

- A. Lincoln: A Biography, by Ronald C. White, Jr., p. 631

- Forty Days, by Joseph Wheelan, p. 190

3.Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, by James M. McPherson, p. 731

sorrowing friend these words: And this too shall pass. Never fear. Victory will come.' Yes,' replied he, 'victory will come, but it comes slowly.'"1

Lincoln when reviewing court martial sentences of soldiers charged with dereliction of duty would, as much as possible, send orders to release them from prison and return to duty. `Doesn't it strike you as queer that I, who couldn't cut the head off of a chicken, and who was sick at the sight of blood, should be cast into the middle of a great war, with blood flowing all about me?'2 he asked a colleague. Though not a member of any Christian Church, he sought comfort in the Bible and would be seen referring to it from time to time.

As the war progressed, he began to believe more and more that man's actions were preordained and shaped by a Higher Power. In his letter to Hodges, from Kentucky, defending his reasons for shifting from his stance of not interfering with slavery towards emancipation of slaves and subsequent black recruitment, he writes:

"I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation's condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God..."3

He again reiterated in a letter:

- The Every-Day Life of Abraham Lincoln: A Narrative and Descriptive Biography with Pen-Pictures and Personal Recollections by those who knew him, by Francis Fisher Browne, chapter XIX

- Lincoln, by David Herbert Donald, p. 514

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Letter to Albert G. Hodges, April 4th 1864, p. 585

"...The purposes of the Almighty are perfect, and must prevail, though we erring mortals may fail to accurately perceive them in advance. We hoped for a happy termination of this terrible war long before this; but God knows best, and has ruled otherwise. We shall yet acknowledge His wisdom and our own error therein. Meanwhile we must work earnestly in the best light He gives us, trusting that so working still conduces to the great ends He ordains. Surely He intends some great good to follow this mighty convulsion, which no mortal could make, and no mortal could stay... "1

Lincoln could find nothing around that could comfort him; on the war front, Sherman had been fiercely battling the enemy to inch his way towards Atlanta but was struggling to get past the confederate army at Pace's Ferry on 5th July; the army of the Potomac was tied up besieging Petersburg. Politically, his own party was split; though the conservatives were supporting him, the Radicals finding him too soft had nominated Fremont for presidency. Peace Democrats charged him for being too harsh and were probably going to opt for a peace platform in their convention in August.

To make things worse, General Lee took a bold step and sent a 15,000 strong confederate strength to attack the capital. Grant had moved most of the force to Richmond to join in the siege, leaving behind a paltry 9000 force to defend Washington. Seeing the approaching enemy, even clerks were handed rifles to defend the city. He was not worried about his safety; in fact he was livid to know that the navy had made preparations to whisk him and his family to safety in case the enemy captured the capital. On July 11th, awaiting reinforcements, Lincoln expectantly looked through his spyglass. He accompanied the troops to Fort Stevens where the battle had begun that morning. He was almost shot

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1858-1865), Letter to Eliza P. Gurney Sept. 4th 1864, p. 627

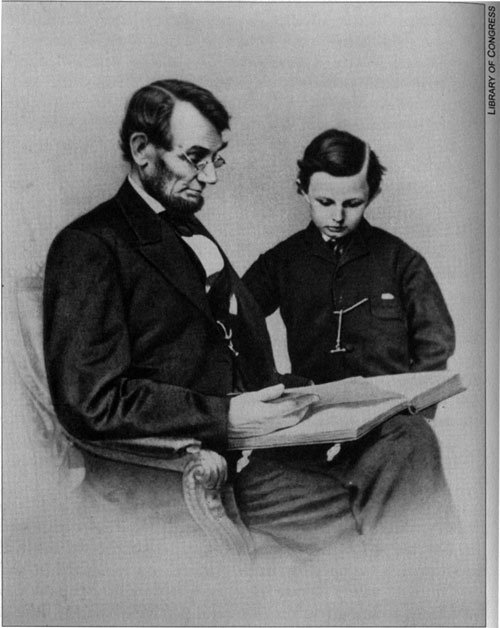

Lincoln with his son Tad in 1864

when he was standing on the parapet surveying the enemy. The confederate general retreated after two days when he saw the steady stream of reinforcements coming in. Lincoln was once again upset that the confederates had been allowed to escape.

With losses mounting heavily, the army needed more troops. Mid July Lincoln found himself again calling for 500,000 more volunteers.

Disconcerted with so much criticism of Grant and of the mounting casualties, taking Tad with him, Lincoln paid a visit to Grant, his generals and his soldiers. The African American troops cheered their president and sang hymns while Lincoln regaled them with his anecdotes; he returned with only a brief word of advice that 'all may be accomplished with as little bloodshed as possible' .1 His visit did much to revitalize and uplift everyone, including Lincoln. Knowing well the lassitude and ineptitude of his War Department with regard to the immediate needs of the war, he instructed Grant that any request to the administration `will neither be done nor attempted unless you watch it every day, and.hour, and force it2 . Lincoln was desperate for a win; during the siege of Petersburg, appreciating Grant's decision to persist, in August he wrote to him to 'hold on with a bull-dog gripe, and choke and chew, as much as possible'3. The war was going to be long and expensive.

Confederate Conspiracy

Around the same time that Washington was attacked by confederate soldiers, Lincoln received a letter from Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Tribune stating that three representatives of the Confederate government, with full authority to negotiate

- Grant, by Jean Edward Smith, p. 377

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), to Ulysses Grant, 3 Aug. 1864, p. 615

- Ibid.,, 17 Aug. 1864, p. 620

a peace, were waiting on the Canadian side of the Niagara Falls. Greeley pressed him to explore the situation; the Union was in a desperate condition, it would not do to let the people believe that the administration was not keen to make peace. Lincoln intuitively sensed a trap. Instinct warned him that it could be connivance between the Peace Democrats and the confederates to ruin the chances of a republican victory. But Greeley was an important opinion maker; any rejection of the peace talks by Lincoln would certainly hurt his reputation during the elections. Shrewdly, Lincoln decided to make the editor an envoy between the administration and the confederates at Niagara. He prepared a letter on 18th July addressed 'To Whom It May Concern', stating that:

"Any proposition which embraces the restoration of peace, the integrity of the whole Union, and the abandonment of slavery, and which comes by and with an authority that can control the armies now at war against the United States will be received and considered by the Executive government of the United States, and will be met by liberal terms on other substantial and collateral points; and the bearer, or bearers thereof shall have safe-conduct both ways."1

These conditions went beyond his emancipation proclamation, which was limited in its scope. Also, the thirteenth amendment to the constitution had just recently failed to pass in Congress. He knew that the slave states would never agree to such a condition.

The response to his letter was worrisome for Lincoln. It gave the Democratic Party more substance to attack Lincoln during their convention scheduled to meet on 29th August; by asking for abolition of slavery, Lincoln had proved that he did not want to end the war, even though an honourable peace was knocking on our doors, they accused. It also boosted their morale to see

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), p. 611

fellow Republicans assail their own nominee.

The Radicals ought to have been congratulating Lincoln for taking such a bold stand against slavery; instead he found himself being charged with incompetence, indecisiveness and leniency towards the rebels. He had enough enemies who looked forward to pulling him down, — already livid with him for pocket vetoing the Wade-Davis bill, this new development gave them another reason to denounce him; they issued a manifesto in August, accusing Lincoln of utilizing reconstruction for securing electors in the Southern states to aid his own reelection campaign and of seizing power from Congress which 'is paramount and must be respected'1. However, the charges were so extreme that their efforts boomeranged on them. Some Radicals Republicans decided to replace Lincoln with another nominee; but Chase declined, as did Charles Sumner. All were waiting for the outcome of the Democratic National Convention.

Lincoln's declaration was also agitating the War Democrats into withdrawing their support. Robinson, the Democratic editor of the 'Green Bay' had been a genuine supporter of Lincoln but War Democrats supported Lincoln's war policy for saving the Union; they did not support the abolition of slavery as a condition for peace talks, he said regretfully. Lincoln wrote a letter defending his actions with regard to the emancipation of slaves on moral grounds, saying that it would be treachery on his part towards the thousands of African Americans who had `come bodily over from the rebel side to ours' and such a disloyalty would not 'escape the curses of heaven'.2 He also defended his actions on practical grounds that without the thousands of African Americans who were fighting for the Union, it would not be possible to save the union. In a desperate bid to prevent the War Democrats from abandoning his reelection, he added towards the end that Wefferson Davis wishes... to know what I would do

- http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1851-1875/the-wade-davis-manifesto-august-5-1864.php

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), To Charles D. Robinson, August 17, 1864, p. 620

if he were to offer peace and reunion, saying nothing about slavery, let him try me' .1

He read out the letter to Frederick Douglass who angrily objected to it and warned him that it would be tantamount to a submission of Lincoln's antislavery policy and could cause a reversal of all that had been accomplished till then. After listening to Douglass whom he had come to respect tremendously, and whose sentiments echoed his own, he decided not to send it to Robinson. He reconciled himself to having lost the allegiance of the War Democrats.

Lincoln's biggest threat came from the conservative Republicans whose support now began to lose its zeal. They believed that his conditions for peace only served to fortify the resolve of the south to defiance, and being war weary, they feared that the war would continue incessantly. Current events on the war front did nothing to disabuse their notion. Also, they did not want to be associated with the abolitionists. The cost of the war was straining the treasury; they needed to procure a massive loan of $200,000,000 to meet their expenses. The siege on Petersburg had recently lost 4000 troops. If the call for volunteers did not produce sufficient men, Lincoln would have to enforce the draft, which would further make him unpopular; Congress having abolished the provision for commutation, the middle class would have no choice but to join the military forces.

With all these problems, even members of his own cabinet like Attorney General Bates and Orville Browning began to lose faith in him. By the end of August, Illinois, his home state, Pennsylvania, Indiana and New York, had all turned against him. Nothing short of a miracle could save his reelection.

Frederick Douglass too had been doubtful about supporting Lincoln in his reelection. In fact, he was leaning towards the radicals but he refrained when he heard of Fremont's nomination. Lincoln invited Douglass to the White House for an urgent meeting. He wanted Douglass to know he supported

1. Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), p. 620

Negro Suffrage as in the case of Louisiana and he wanted to ask Douglass for a favour.

On August 19, 1864, Lincoln met Frederick Douglass at the White House. He apprised him of the grave situation and asked for his assistance in mobilising escaped slaves to volunteer for the Union Army. Douglass was impressed with his meeting with Lincoln. On August 29th, he wrote to Lincoln:

"All with whom I have thus far spoken on the subject, concur in the wisdom and benevolence of the idea, and some of them think it is practicable. That every slave who escapes from the Rebel States is a loss to the Rebellion and a gain to the Loyal Cause, I need not stop to argue; the proposition is self evident. The negro is the stomach of the rebellion. I will therefore submit at once to your Excellency — the ways and means by which many such persons may be wrested from the enemy and brought within our lines."1

What troubled Lincoln was the fate of the nation; facing squarely the faint chances of his reelection, Lincoln decided to do the best he could to save the union. Concentrating on that aspiration he prepared a memorandum on 23rd August 1864:

"This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he can not possibly save it afterwards."2

During the next cabinet meeting he asked his members to sign at the back of the sealed document. He had decided that in

- Frederick Douglass: Reformer and Statesman, by L. Diane Barnes, p. 179

- Lincoln: Speeches and Writings (1859-1865), p. 624

the likely chance of his losing the elections, he would speak to McClellan, probably the president elect, to urge him to unite his influence over the people with his governmental powers to save the country. He was doubtful if McClellan would join hands with him, but 'at least... I should have clone my duty and stood clear before my own conscience'1.

The Democratic Party had swelled its numbers; the War Democrats had returned to its fold. On 30th August 1864, at the Democratic National Convention, War and Peace Democrats unanimously announced General George McClellan, a War Democrat as their presidential nominee and adopted a party platform, which declared:

"After four years of failure to restore the Union by the experiment of war, during which, ... the Constitution itself has been disregarded in every part, ... justice, humanity, liberty, and the public welfare demand that immediate efforts be made for a cessation of hostilities, ... that... peace may be restored on the basis of the Federal Union of the States."2

On the same day, extreme Radical Republicans like Greeley and Davis, still keen to replace Lincoln as presidential nominee, met in New York City and sent letters to various governors, but did not receive any resolute response from them. By the second week of September their plot to derail Lincoln crumbled.

In the meantime, unable to face his comrades after having fought so many battles with them, McClellan disowned the Democratic peace platform. It had been a desperate combination of a war nominee on a peace plank by the Democrats to keep their party united — one that from the beginning seemed

- Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, by John Hay, p. 248

- The American Conflict: A History Of The Great Rebellion, By Horace Greeley, p. 668

unlikely to succeed.

General Sherman's capture of Atlanta on 1st September, came as a Godsend. On the heels of the victory of Atlanta came the capture of Mobil, the last important port under confederate control. Relieved, Lincoln declared a day of thanksgiving and prayer for 'the glorious achievements of the Army ... in the capture of the City of Atlanta, call for devout acknowledgement to the Supreme Being in whose hands are the destinies of nations...'1

With the change of tides in war came the change in the demeanor of the Radicals; they began to criticize the peace plank of the Democrats, hailed the victories by Sherman and men like Greeley began campaigning for the Republican Party.

Lincoln, once again in full spirits, decided that it was time to unite his party and win back the support of the Radicals. He knew that though they did not have much regard for him, some Radical Republicans would rather support him than see McClellan or any other Democrat as president of the United States. They agreed to support his reelection but demanded the resignation of Montgomery Blair, Lincoln's Postmaster General. Lincoln was very fond of Blair who had fervently supported Lincoln's renomination but he was aware of his hostility towards the abolitionists. The radicals also offered to secure the withdrawal of Fremont from the presidential race if Lincoln agreed to the removal of Blair from his cabinet. Lincoln was unhappy, not only because it was unfair to Blair but mainly because he disliked being put to ransom. Responding honestly to Thaddeus Stevens, who came bearing the conditional offer, he said:

"...Am I to be a mere puppet of power — to have my constitutional advisers selected for me beforehand? I confess that I desire to be re-elected... I have the common pride of humanity to wish my past four years Administration endorsed; and besides I honestly believe that I can better

1. Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 7, page 533, Proclamation of Thanksgiving and Prayer, 3rd September 1864

serve the nation in its need of peril than any new man could possibly do...."1

Though Lincoln was sure that Fremont's nomination was hardly a threat to his own, he did not want to lose the votes of the American-Germans who zealously supported him, as that could lose him the election to McClellan. He accepted the radical offer reluctantly.

Fremont, seeing his support slipping, finally withdrew from the race, announcing that he did so not because he supported Lincoln but because he did not want to see slavery restored in the union under McClellan.

With the crumbling of the Fremont campaign, it was a straight fight between McClellan and Lincoln. It became easier for him to get the last segment of Radicals within his fold. Chase, still smarting from his removal from the cabinet had been quietly emboldening the anti Lincoln movement. The position of Chief Justice appealed to him; with the fall of Atlanta, Mobil and Fremont's campaign, he decided to publically appreciate Lincoln as it was in his interest to support him. He began sending feelers to Lincoln to consider him for the post. However, Lincoln had many other contenders for the same post, Stanton being one of them, and Montgomery Blair, the other. Despite urgent requests from Sumner on behalf of Chase, Lincoln did not respond. Desperate to please Lincoln, Chase finally entered the campaign actively, travelling from town to town, to push for his reelection.

In the meantime, by October, General Sheridan had pushed the confederates out of Shenandoah Valley, Virginia and burnt the farms thereby cutting off the rebel's food supply; in the west, Sherman had destroyed Atlanta and began his march to the sea, destroying buildings, factories, farms and railroads on his way, making life insufferable for the Georgians. Lincoln was criticized for allowing Sherman to wreak this carnage, the Southerners hated him; but it was not his ruthlessness to see the

1. Conversations with Lincoln, Charles M. Segal, p. 338

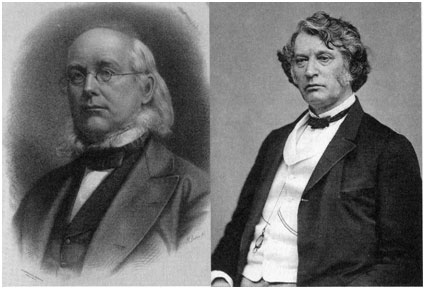

Left: Horace Greeley, and right: Charles Sumner - both Radical Republicans who urged Lincoln towards emancipation

South destroyed but his aspiration to shorten the war and reduce casualties. He wanted to begin the process of mending the rift, but to accomplish that he first needed to end the war.

For Lincoln, the preservation of the union was still of utmost importance; despite urgent requests from fellow republicans he did not postpone the military draft, though it was an unpopular measure. The enemy was on its last legs and the union army needed more men to win the war and he would do anything to ensure that.

He found himself mediating between his own campaigners whose quarrels were proving detrimental to their own party prospects. He ensured that soldiers in the field cast their votes. Since Indiana did not allow its soldiers to cast their votes for the state elections while they were on duty, and it was important to ensure a republican victory in the state, he requested Sherman to

furlough1 them to go home and vote, adding that 'they need not remain for the Presidential election, but may return to you at once'. Government employees in Washington were given leave too to go home and vote.

Disabusing the supposition of the Democrats and Radicals, he did not admit Colorado and Nebraska as new states or readmit Louisiana and Tennessee, (southern states undergoing reconstruction but still under military control), before the elections to increase his electoral votes. The election process was under the jurisdiction of the Congress; his duty was only to grant protection to ensure that it took place peacefully.

African-Americans by and large wanted him to win; a major part of the Abolitionists supported him completely, as did most denominations of the Church. People of the North grew to respect him, having witnessed his trials and tribulations over the years. H.W. Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom's Cabin) and Ralph Waldo Emerson, great writers of that period admired Lincoln. During the elections Emerson remarked, `Seldom in history was so much staked on the popular vote2'. Both believed that public decision very often determined the fate of the nation and their readiness to move towards a greater destiny. Perhaps his greatest supporter among the press was James Lowell, editor of North American Review who influenced public opinion by printing extended articles during 1864 in praise of Lincoln.

- Military leave

- History of the Civil War, 1861-1865, by James Ford Rhodes, p. 339

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet