Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body - Cricket - Jam Sahib Of Nawanagar

Cricket

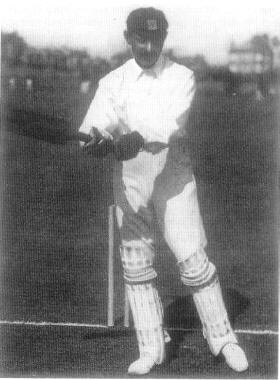

The Jam Sahib of Nawanagar*

As cricket is a very special game in India, we felt that, even if we could not hope to bring stories about every possible games, we should at least have one on cricket. We found a very refreshing short essay by A.G. Gardiner about Ranjit Singh, a Prince Batsman who enchanted quite long ago the British and Indian crowds, a legend in the annals of cricket.

The last ball has been bowled, the bats have been oiled and put away, and around Lord's the grandstands are empty and sad looking. We have said goodbye to cricket. We have said good bye, too, to cricket's king. The game will come again with the spring and the new grass and the blossoming tree. But the king will come no more. For the Jam Sahib is forty, and alas, the Jam Sahib is fat. And the temple bells are calling him back to his princely duties amid the sun shine, and the palm trees, and the spicy garlic smells of Nawanagar. No more shall we see him running lightly down the pavilion steps, his face wreathed in chubby smiles, no more shall we sit in the jolly sunshine throughout the day and watch his incomparable art till the evening shadows fall across the grass and send us home content. The actor with the many graces leaves the stage and becomes only a memory in a ' world of happy memories. And so 'hats off to the Jam Sahib — the prince of a little State, but the king of a great game....

I think it is undeniable that as a batsman the Indian will live as the supreme master of the Englishman's game. The claim does not rest simply on his achievements, although, judged by them, the claim could be sustained. His season's average of 87 with a total of over 3,000 runs, is easily the highest point ever reached in English cricket. Three times he has totalled over 3,000 runs, and no one else has equalled that's

* Nawanagar is also known as Jamnagar, on the west coast of India, not far from Dwarka, in Saurashtra, Gujarat.

record. And is not his the astonishing achievement of scoring two double centuries in a single match on a single day — not against a feeble attack, but against Yorkshire, always the most determined and resourceful of bowling teams? , .

But we do not judge a cricketer so much by the runs he gets as by the way he gets them. In literature as in finance,' says Washington Irving, 'much paper and much poverty may exist side by side.' And in cricket, too, many runs and much dullness may be associated. If cricket is menaced with creeping paralysis, it is because it is losing the spirit of

joyful adventure and becoming a mere instrument for building up tables of averages. There are dull, mechanic fellows who turn out runs with as little emotions as a machine turns out pins.... There is no colour, no enthusiasm, no character in their play. Cricket is not an adventure to them: it is a business. It was so with Shrewsbury. His technical perfection was astonishing; but the soul of the game was wanting in him. There was no sunshine in his play, no swift surprise or splendid unselfishness. And without these things, without gaiety, daring and the spirit of sacrifice, cricket is a dead thing. Now the Jam Sahib has the root of the matter in him. His play is as sunny as his face. He is not a miser storing up runs, but a millionaire spending them, with a splendid yet wise generosity. It is as though his pockets are bursting with runs that he wants to shower with his blessings upon the waiting crowds. It is not difficult to believe that in his little kingdom of Nawanagar, where he has the power of life and death in his hands, he is extremely popular, for it is obvious that his pleasure is in giving pleasure.

In the quality of his play he is unlike anything that has been seen on the cricket field, certainly in our time. There is extraordinarily little display in his methods. He combines an Eastern calm with an Eastern swiftness — the stillness of the panther with the suddenness of its spring. He has none of the fine flourishes of our own stylists, but quite a startling economy of action. The normal batsman, obeying a natural impulse, gets into motion as the bowler starts his run. He seems to try to move at the same speed as his enemy, and his movements gradually get faster and faster until they reach a crisis. At the end of the stroke the bat has moved in a circle, the feet are out of place, the original attitude has been lost in a whirl of motion.... The style of the Jam Sahib is entirely different. He stands motionless as the bowler approaches the wicket. He remains motionless as the ball is delivered. It seems to be on him before he takes action. Then, without any flourish as a preparation for the stroke, the bat flashes to the ball, and the stroke is over. The body seems never to have changed its position, the feet apparently unmoved, the bat is as before. Nothing has happened except that one sudden flash — swift, perfectly timed, indisputable.

'Like the lightning, which doth cease to be

Ere one can say it lightens.'

If the supreme art is to achieve the maximum result with the mini mum effort, the Jam Sahib, as a batsman, is in a class by himself. We have no one to challenge with our coarser methods that curious delicacy and purity of style, which seems to have reduced action to its simplest form.... The typical batsman performs a serial of complicated movements in laying the ball; the Jam Sahib makes a slight movement of his wrist and the ball races to the ropes. It is not a trick nor magic: it is simply the perfect economy of means to an end. His batting may be com pared with the public speaking of Mr Asquith [a prominent British politician], who is as economical in the use of words as the Jam Sahib in the use of action, and achieves the same completeness of effect. The Jam Sahib never uses an action too much; Mr. Asquith never uses a word too many. Each is a model in the fine art of omission of unessentials, that concentration on the one thing that needs to be said or done....

Probably no cricketer has ever won so special a place in the affections of the people.... It is the Jam Sahib's supreme service that through his genius for the English game, he has made the English people familiar with the idea of the Indian as a man of the same affections with our selves, and with capacities beyond ours in directions supposed to be particularly our own. In a word, he is the first Indian who has touched the imagination of our people....

And if India has sought to make herself heard and understood by the people who control her from a long distance away she could not have found a more triumphant missionary than the Jam Sahib, with his smile and his bat. 'Great Indians come to us frequently, men of high scholar ship, rare powers of speech, noble character — the Gokhales, the Bannerjees, the Tagores. They come and they go, unseen and unheard by the mass of the people. The Jam Sahib has brought the East into the heart of our happy holiday crowds, and has taught them to think of it as something human and kind-hearted, and keenly responsive to the joys that appeal to us....

He goes back to his own people — to the little State that he recovered so romantically, and governs as a good Liberal should govern — and the holiday crowds will see him no more. But his name will live in the hearts of hundreds of thousands of British people, to whom he has given happy days and happy memories.

Related Books

- Alexander the Great

- Arguments for The Existence of God

- But it is done

- Catherine The Great

- Danton

- Episodes from Raghuvamsham of Kalidasa

- Gods and The World

- Homer and The Iliad - Sri Aurobindo and Ilion

- Indian Institute of Teacher Education

- Joan of Arc

- Lenin

- Leonardo Da Vinci

- Lincoln Idealist and Pragmatist

- Marie Sklodowska Curie

- Mystery and Excellence on The Human Body

- Nachiketas

- Nala and Damayanti

- Napoleon

- Parvati's Tapasya

- Science and Spirituality

- Socrates

- Sri Krishna in Brindavan

- Sri Rama

- Svapnavasavadattam

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- The Aim of Life

- The Crucifixion

- The Good Teacher and The Good Pupil

- The Power of Love

- The Siege of Troy

- Uniting Men - Jean Monnet